(Credits: Far Out / Thomas Hawk)

Within certain professions, there are figures that are so head and shoulders above the rest that they almost single-handedly elevate their entire work into an art form. Think Daniel Day-Lewis for acting or Bruce Springsteen for New Jersey-centric rock music. Every occupation has a revolutionary figure attached to it, and for film criticism, that figure was Roger Ebert.

The old adage goes that they “don’t build statues of critics”, but when the naturally smug utterer of that particular sentence looms into your visage, make sure you show them the directions to Ebert’s statue in Illinois. The bronze vision of the critic with his thumb up reminds us all that no matter your profession if you are highly skilled and well-loved, you will never be forgotten.

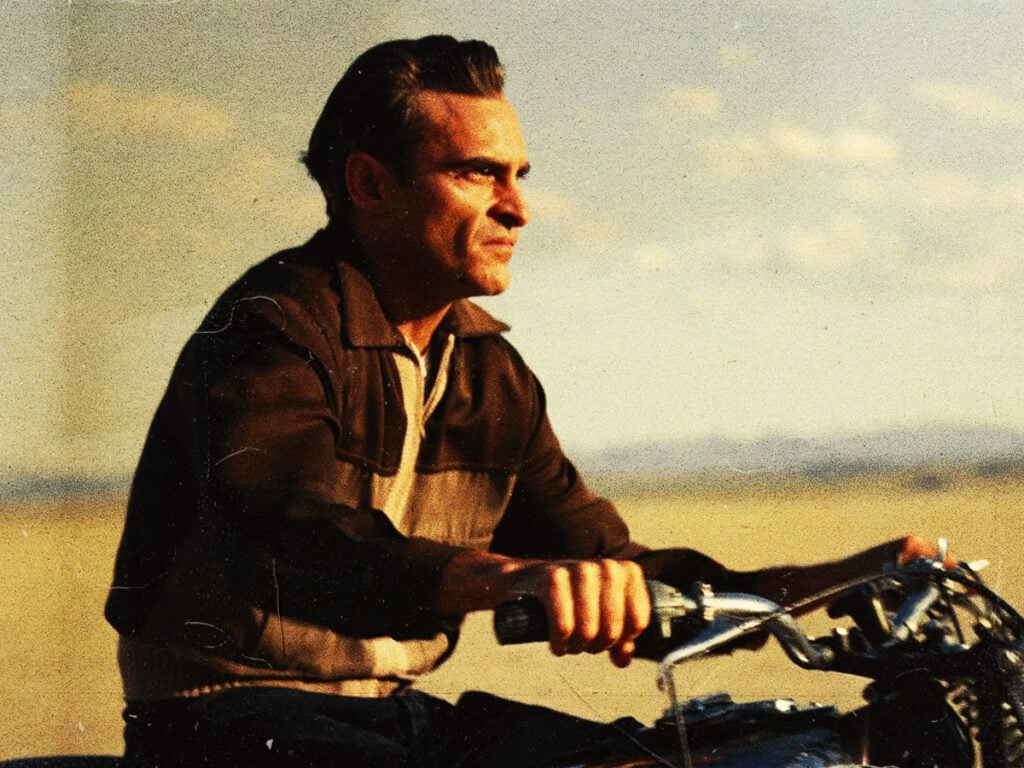

A stocky midwesterner with a predilection towards storytelling, Ebert ascended to the position of Chicago Sun-Times in 1967, just as American cinema was experiencing a major overhaul in style. With every new development, whether it was the hyperviolence of Bonnie and Clyde, the drug-fueled counterculture of Easy Rider, or the mainstream acceptance of niche genres like horror with Night of the Living Dead or sci-fi and the masterful 2001: A Space Odyssey, Ebert was there to contribute his informed opinion.

Part of what made Ebert so successful was his relatability. This wasn’t a man in a three-piece suit pushing an esoteric art film to an audience of hoighty intellectuals. Ebert’s greatest philosophical enemy was pretension. He had a manic love for movies, and he strove to prioritise one specific element that guaranteed a movie’s success: entertainment. A film could be cheap, low-brow, excessive, or nonsensical to a fault, but as long as there was something compelling about it, Ebert would highlight it. Forget the relentless chicness of classic cinema or the predilection for arthouse audiences to love arthouse cinema simply because it was confusing. Ebert believed that enjoyment and entertainment were the name of the game when it came to movies.

Ebert didn’t care what the prevailing narrative around a film was. He had his own metrics to judge success, and more often than not, those metrics made his reviews incredibly readable and incredibly relatable to the people who poured over his work week after week. It was like asking what your buddy thought of a movie over a beer: that sense of looseness and easy humour was integral to Ebert’s reviews. There were plenty of occasions when Ebert’s sub-1,000-word reviews were more hilarious than the two-hour comedy it was reviewing.

But his dedication to his own style and his extensive career of over 50 years of film criticism, meant that Ebert missed the mark every once in a while. Sometimes, his dissension was part of an overall polarising reception, but Ebert was also unafraid to fly in the face of acclaim. Ebert’s infamous ‘Most Hated’ films list contains some truly baffling picks, and his collection of reviews in the book I Hated, Hated, Hated This Movie is a fascinating deep dive into some truly awful but occasionally wonderful films. The kind of duality that would have undoubtedly pleased Ebert.

To use some baseball parlance that any true Chicago resident would appreciate: nobody bats a thousand. Ebert’s occasional mystifying hatred of a movie only endears him that much more as a man of integrity or of specific dedication to his craft. If Ebert didn’t like a movie, he never faked it just to hop on the bandwagon of critical adulation. Ebert was unafraid to be iconoclastic, and even his most unagreeable opinions were still wildly entertaining to take in.

To know Ebert is to know that he, too, could be wrong. No transcendent figure is perfect, and Ebert could be crotchety, wishy-washy, hardened, bullish, and even downright cynical. There are times when he completely missed the point of a movie or that his eventual rating would contradict the content within a review. To err is human, and the best part about Roger Ebert is that he always seemed human. Here are some examples of his criticisms that haven’t quite aged as well as the man himself.

10 great films that Roger Ebert hated:

Dead Poets Society (Peter Weir, 1989)

Roger’s Score: Two stars

One of the endearing qualities of Roger Ebert was that he was human. A very smart, well-balanced human, but a human nonetheless. That means that he was fallible and could find the most charming and rewatchable of films pretentious and poorly made. That’s the case with Peter Weir’s exemplary Dead Poets Society, which Ebert famously led off his review by calling, “A collection of pious platitudes masquerading as a courageous stand in favour of something: doing your own thing, I think”.

Ebert criticised Robin Williams’ performance for slipping into his comedic persona and found the film overwrought, opinioning that “when [Williams’] students stood on their desks to protest his dismissal, I was so moved, I wanted to throw up”. Ouch.

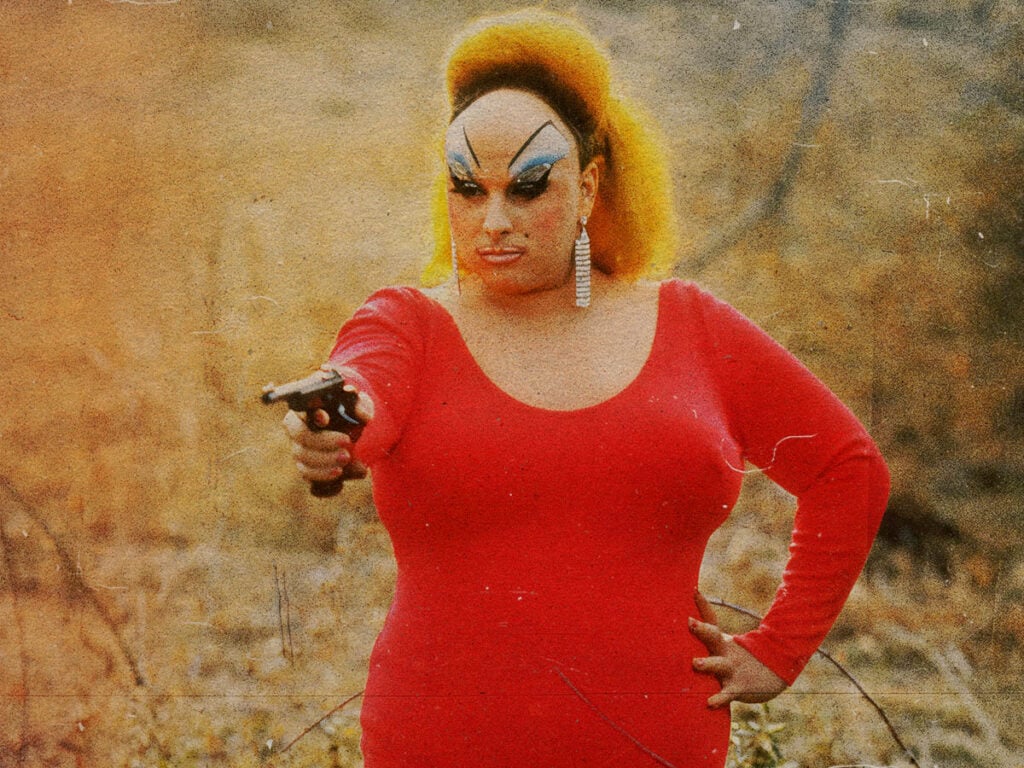

Pink Flamingos (John Waters, 1972)

Roger’s Score: No stars

John Waters’ bad taste opus Pink Flamingos is one of only a handful of rare films that are just as transgressive today as they were when they first hit arthouse cinemas in 1972.

Featuring scenes depicting fake rape and vomit along with real prolapsed anuses and coprophagia, Pink Flamingos is as disgusting and essential to American cinema as it ever was. Ebert found the gross-out moments unsavoury without substance and famously promised to retire if forced to view the film on its 50th anniversary. That anniversary arrived in 2022, and although sadly Ebert had passed on, his hilariously scathing review keeps his legacy alive.

The Master (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2012)

Roger’s Score: Two and a half stars

The movies that Ebert gave two and a half stars are more fascinating than the films that he directly praises or pans. It’s the most ignominious rating that the late Ebert doled out, and it was indicative of a well-made film that was missing an essential element towards its success.

It’s hard to believe that Paul Thomas Anderson’s magnetic The Master failed to connect with Ebert, but the critic found the lead performances by Philip Seymour Hoffman and Joaquin Phoenix sterile and the movie to be confused about its own message. Ebert describes the film as “fabulously well-acted and crafted, but when I reach for it, my hand closes on air. It has rich material and isn’t clear what it thinks about it”.

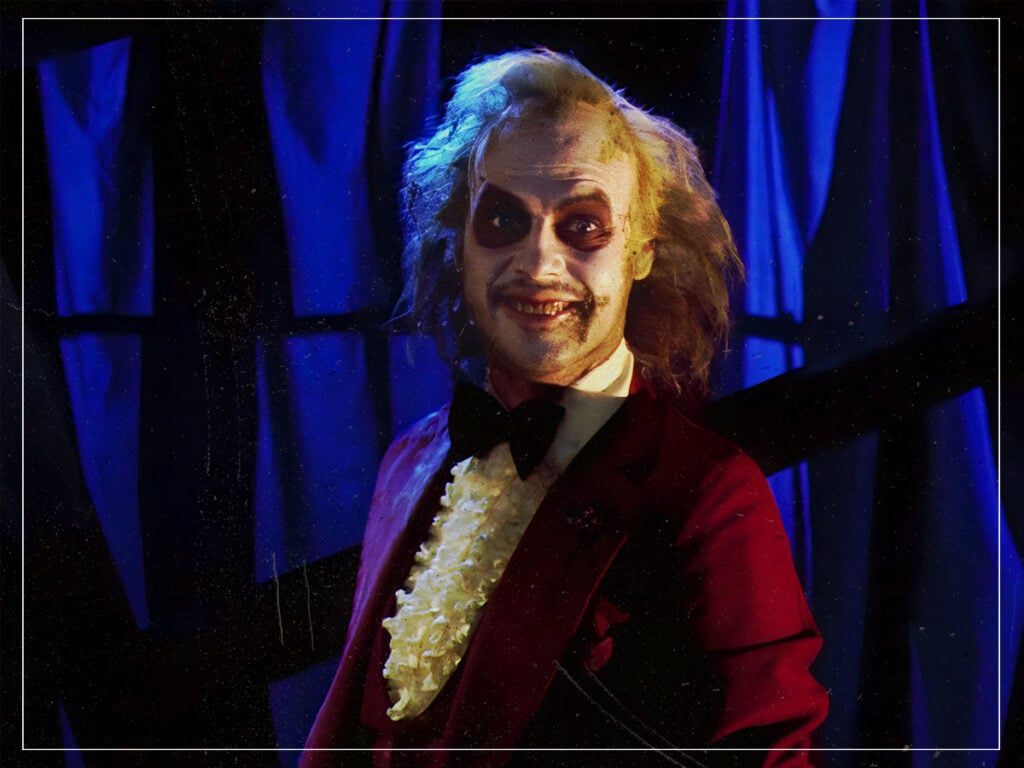

Beetlejuice (Tim Burton, 1988)

Roger’s Score: Two stars

Ebert’s relationship with Tim Burton was always tricky. Ebert gave low marks to some of the director’s most beloved films, including blockbusters like Batman, hallmarks like Edward Scissorhands, and cult classics like Mars Attacks!, all of which he gave two stars. But his refusal to buy into the charms of Beetlejuice seems the most egregious.

Describing the film as “All anticlimax once we realise it’s going to be about gimmicks, not characters,” Ebert proceeds to take Michael Keaton’s legendary title performance to task, explaining: “His scenes don’t seem to fit with the other action, and his appearances are mostly a nuisance.” Ebert does praise the set design though, so there’s that, but otherwise, the whimsical wonder of Burton’s creation is seemingly lost on Ebert.

A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971)

Ebert’s Review: Two stars

Ebert was around for long enough to cover over 50 years of change and evolution in Hollywood. He had a front-row seat as the studio system yielded to the auteurs of the late 1960s and early ‘70s and gave effusive praise to legendary Stanley Kubrick in his reviews for The Shining, Barry Lyndon, and Dr. Strangelove. But when it came to the ultraviolence of 1971’s A Clockwork Orange, Ebert was one of many critics who baulked at the film.

For the critic, it would seem that the premise of the movie strayed too far away from being anything cognisant of his simple appreciation for entertainment.

Describing the film as “an ideological mess, a paranoid right-wing fantasy masquerading as an Orwellian warning,” Ebert spends the early part of the review unable to either sympathise or connect with the story’s main character, Alex DeLarge. “I don’t know quite how to explain my disgust at Alex (whom Kubrick likes very much, as his visual style reveals and as we shall see in a moment). Alex is the sort of fearsomely strange person we’ve all run across a few times in our lives — usually when he and we were children, and he was less inclined to conceal his hobbies.”

The Elephant Man (David Lynch, 1980)

Roger’s Score: Two stars

David Lynch is another director with whom Ebert has an oscilating relationship with. While Lynch’s films Mullholland Drive and The Straight Story both received four stars in their reviews, other movies like Lost Highway and Blue Velvet were given more middling reviews, with the latter only receiving a single star.

Dismissing The Elephant Man as “pure sentimentalism”, Ebert’s review mainly focused on how shallow the film was by celebrating John Merrick’s ability to live, rather than the deeper questions of what kind of person he was.

It was a somewhat unique position that has grown a little weary as more and more reto-active reviews lavish the movie with praise. “I kept asking myself what the film was really trying to say about the human condition as reflected by John Merrick, and I kept drawing blanks,” Ebert reflects. It’s fine to disagree with Ebert’s assessment, but like his best work, he causes you to look at a commonly held narrative and reassess it in a new light.

Fast Times at Ridgemont High (Amy Heckerling, 1982)

Roger’s Score: One star

As we’ve seen most of Ebert’s less kind reviews can still find promise or solid qualities in a film. It’s rare for Ebert to completely go against a film’s normal reputation or to truly degrade a movie, but that accomplishment goes to Fast Times at Ridgemont High, the Amy Heckerling ‘80s classic that is currently preserved in the Library of Congress.

The picture has now become as ubiquitous to the 1980s lifestyle as spandex and oversized socks. But for Ebert, things simply fell flat.

If Ebert had his way, however, the film would be preserved in a landfill somewhere. “The makers of Fast Times at Ridgemont High have an absolute gift for taking potentially funny situations and turning them into general embarrassment. They’re tone-deaf,” Ebert says, referring to the film as a “scuz-pit of a movie” that wastes the young talent it has assembled. Teen comedy is as divisive a genre as any, but Ebert’s contempt for Fast Times remains baffling 40 years later.

Fight Club (David Fincher, 1999)

Roger’s Score: Two stars

A question as old as time itself: is Fight Club a biting satire on machismo and young male rage or propaganda promoting those very same ideals? It’s hard to argue that David Fincher takes viewers on a masterful ride through the ever-devolving mind of Edward Norton’s narrator, but Ebert was one of many critics who left the film with a bad taste in his mouth.

He describes the film as “macho porn — the sex movie Hollywood has been moving toward for years, in which eroticism between the sexes is replaced by all-guy locker-room fights”. Over time, the verdict on Fight Club has flip-flopped, but his assertions aren’t far wrong.

Ebert seems to understand the cultish nature of following Tyler Durden despite his lack of worthwhile answers. However, he senses that audiences won’t key into the philosophy being peddled because Fincher makes the fights and the Durden lifestyle too intoxicating to rebuke. It’s a rare review in which Ebert seems to have little faith in the audience, contrasting his usual position as a voice of the common man.

Napoleon Dynamite (Jared Hess, 2004)

Roger’s Score: One and a half stars

No duo has a shadier relationship than Roger Ebert and comedies. That’s not entirely Ebert’s fault, seeing as comedy is inherently subjective, and the funniest of films often have an afterlife beyond whatever critical pounding they take upon release. However, one of the biggest contrasts between Ebert’s take and the legacy of a film comes with Jared Hess’ 2004 cult classic, Napoleon Dynamite.

“There is a kind of studied stupidity that sometimes passes as humour, and Jared Hess’ Napoleon Dynamite pushes it as far as it can go,” Ebert stated. Ebert found the central character of Napoleon unlikeable and the oddball humour of the film to be too self-defeating, much like Ebert’s take on Napoleon himself. Maybe it shouldn’t be surprising that a then-62-year-old man wasn’t howling at lines like “I’m training to become a cage fighter” and “How much you wanna bet I can throw a football over them mountains?”

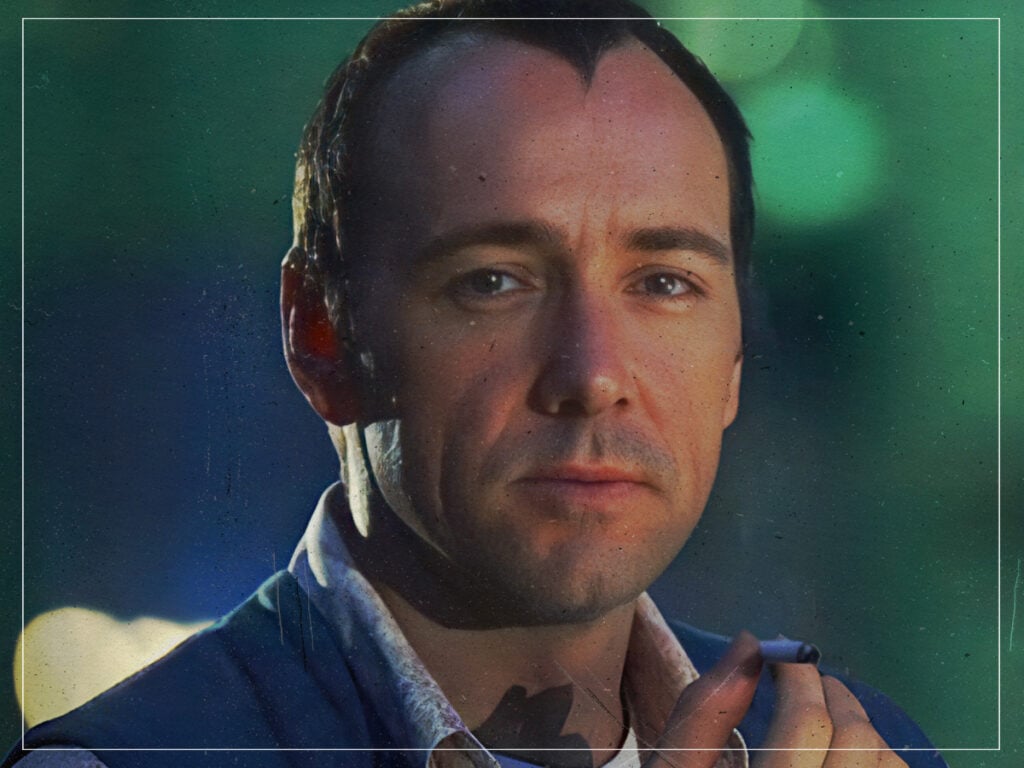

The Usual Suspects (Bryan Singer, 1995)

Roger’s Score: One and a half stars

In the wake of Quentin Tarantino’s dominance of Hollywood in the early ‘90s, sharp-witted crime films with anti-heroes making up the majority of the film became the new hot commodity among studios, and anyone who was willing to offer up a half-baked script was given a green light.

One of the few movies to actually rise to the occasion was The Usual Suspects, although you wouldn’t know it from Ebert’s review, who deemed the cult classic a dud among his staunch reasoning.

Ebert spends most of his review befuddled by the film’s plot and scorned at being manipulated by the finale, summarising his findings with the statement: “To the degree that I do understand, I don’t care.” It took quite a dud to find its way onto Ebert’s ‘Most Hated’ film list, the dark twin of his famous ‘Great Movies’ list, but The Usual Suspects was prominently featured despite its otherwise glowing reviews.

Related Topics

Subscribe To The Far Out Newsletter

This post was originally published on here