South America is not the first place that comes to mind as a destination for British travellers. Last year, more visits were made by Britons to Canada than all the South American countries put together. Yet the continent is the focus of a venerable British travel book that celebrates its centenary this year — the longest-running guidebook currently published in the English language.

The South American Handbook was launched in 1924 and its next edition will appear next year. Among its users was the writer Graham Greene, for whom it was “the best travel guide in the world”. It is a staggeringly compendious resource: the latest version runs to more than 1,800 pages. It has a reputation as a travel bible, a volume containing all the answers to life’s mysteries — such as where to find a decent meal in Cruzeiro do Sul, “an isolated Amazonian town of 10,000 people”, according to my 1990 edition.

I took the Handbook with me while travelling around South America, from Venezuela down into the Amazon and then on through Brazil to Argentina, and back up again via the Andes. I was 18 and on my gap year — otherwise known as “gap yah”, in mimicry of the plummy vowels of the privately educated British school leaver adventuring to faraway lands before going to university. (Guilty as charged!)

My Handbook survived six months’ intensive use. It is a battered but resilient hardback with a colourful illustration of a jaguar and a macaw in the rainforest on the cover. In the thin blank pages at the very back I find a list of Argentine wines written in my youthful hand, including one called “Terminador” accompanied by an exclamation mark — evidently the relic of some vicious hangover. Two pages have been torn out for purposes unknown. I don’t think it was for the same reason as a friend who, on his gap travels, repurposed the section on Paraguay as rolling paper for spliffs.

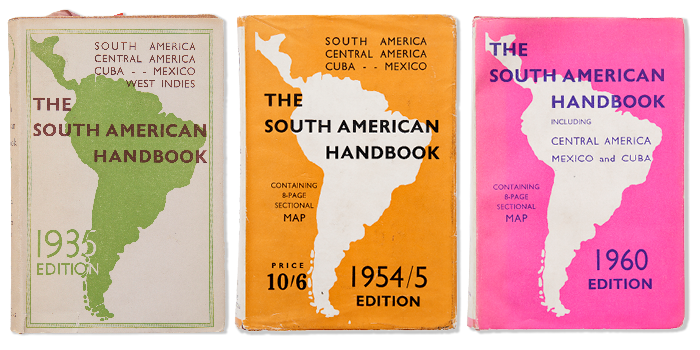

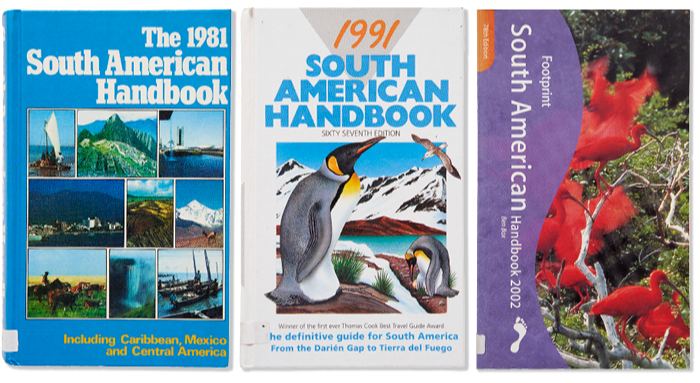

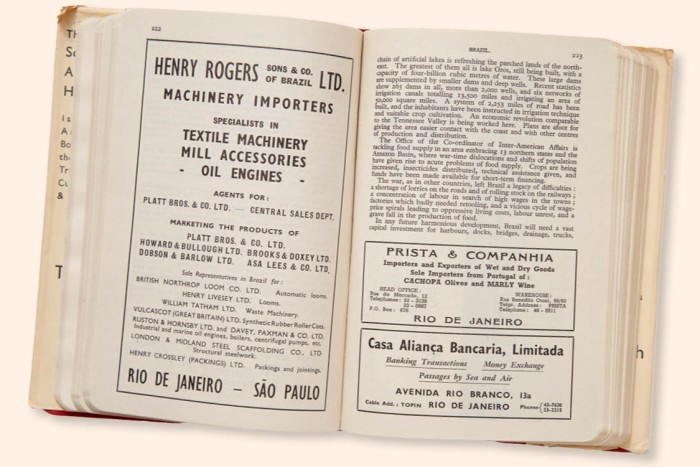

Back when the first Handbook appeared, there was no such thing as a backpacker with coagulating clumps of dreadlocks clad in indigenous Andean clothing and a beret from Buenos Aires (er, guilty as charged). The 1924 edition was aimed at commercial travellers in an era when Britain was a principal trading nation with South America, and Argentina had the largest population of British residents outside the empire or the US. One of them was my grandfather, a three-year-old boy living in Buenos Aires when the first Handbook appeared.

Included in its 660 pages is advice about “the British status of Argentine-born children” like him. A glossary has the Spanish words for hall porter (“El portero”) and invoice (“La factura”). Visitors to the Andes are advised that “it is incumbent upon the traveller to take his own saddle and blankets”. Amid warnings about “primitive methods” of washing clothes and the advisability of having “a good automatic electric lamp”, a reassuring note is struck: “For formal occasions such toilettes are suitable as would be worn for similar gatherings at home.”

The 1920s business traveller would have been affronted by my 1990 Handbook’s admonishment not to have “a generally dirty and unkempt appearance” and for “users of drugs, even soft ones” to be “particularly careful”. It was written for a readership that went from top-end types staying in five-star hotels to backpackers like myself and my gap-year companion John, scouring its tiny print for $1-a-night hostels.

Ben Box edited that edition. “It was intended to be the most comprehensive guide to Latin America for independent travellers and, to a lesser degree than it used to be, business visitors,” he tells me, speaking from his home in Suffolk. The 1990 Handbook was his first as editor, a role he held until his retirement, aged 71, last year.

The editions were updated annually until 2018, with much of the information sourced from readers. Like Wisden, the cricketing bible, the South American Handbook conveys the unobtrusive impression of knowing everything there is to know about its topic. John and I were delighted when we managed to visit a town that had escaped its notice — a nondescript Brazilian municipality called Coronel Fabriciano, where we were introduced to people as “international men from the land of Paul McCartney”.

“The aim,” Box says of the Handbook, “was to give you everything you needed in one relatively manageable package.” Its commercial heyday was in the early 1980s, when sales ran to almost 30,000 copies. “Then the Falklands war came along,” Box says. Britain’s conflict with Argentina in 1982 caused a collapse in British visits to South America. “Sales plummeted in 1983, absolutely plummeted,” Box remembers. There had been a recovery by the time I went, although the longer-term sales graph trended downwards.

These days the Handbook has to contend with an even more comprehensive resource, the internet. “The whole nature of travel planning and travel itself has changed, which feeds into the long-predicted death of guidebooks,” says Adrian Phillips. He is a travel writer and also managing director of Bradt Guides, which now publishes the South American Handbook. “The guidebook market has seen a decline since the late 1990s or early 2000s,” he tells me. “But it has defied predictions that it would be extinct by this time.”

Bradt took over the South American Handbook in 2019 when it purchased the book’s previous publisher, Footprint Travel Guides. “The timing wasn’t the best because then the pandemic hit,” Phillips says. “But one of the attractions to us was the fact that they had the South American Handbook, which has such heft in terms of guidebook history.”

The 2025 edition is due to appear next summer. “It is a great honour to carry the mantle as this legendary guidebook moves beyond its 100th year,” says its new editor, Daniel Austin. The updated version will feature almost 9,000 hotels, restaurants and other businesses, alongside countless churches, museums, national parks and so on. “One in five of the listed businesses have closed down since the last edition, no doubt many of them casualties of Covid,” Austin explains. “So the new edition will feature more than 1,500 never-before-included hotels and restaurants across the continent.”

“It’s difficult to know how it will sell,” says Phillips, Bradt’s MD. “We’re taking it on because we’ve got faith in the history and quality of the book. Obviously, it will be the first edition that we’ll have produced, so we don’t yet know what the sales potential will be and whether there will be appetite for travellers to want this sort of comprehensive tome or not. We’ll see.”

Is it a pipe dream to imagine the Handbook celebrating its 150th anniversary in 2074? “Oh crumbs,” Box says. “Well, it would be brilliant to think it could still be going then. Tourism is in a very mixed-up place at the moment. But I still believe that the interchange of cultures and ideas through people meeting and talking to each other, seeing how other people live and sharing experiences with them, is as important as anything you can do.”

His words echo the quotation by Elizabethan philosopher and statesman Francis Bacon printed on the title page of the copy that I carried around South America in my backpack. “Travel, in the younger sort, is a part of education,” Bacon states; “in the elder, a part of experience.” I’ll raise a glass to that — although not of the Terminador variety. Long may the South American Handbook and its ethos endure.

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen

This post was originally published on here