When my son was in the third grade, we joined the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Backyard Bird Count. A form of community science — research in which volunteers gather or analyze data — the event has hundreds of families observing and recording the birds they see in their neighborhoods. It’s a simple but effective way for researchers to gather a robust database of bird populations across the US. Meanwhile, volunteers enjoy a fun way to connect with science and the natural world.

That year’s count also happened to be smack-dab in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, a time when we were closer to the birds than anyone else in town. With time on our hands, my family got into birding. Really into it. My son made birds the focus of his science fair project. We took long walks to watch wintering Barrow’s goldeneyes and the spring nests of great blue herons. And I read books on everything from local species to the evolutionary history of feathers.

Since then, life has sped up from its pandemic lull. My workload has gotten more demanding, and my son lives the fast-and-furious lifestyle of a socially active middle schooler. Our time for engaging in family hobbies is fleeting, to say nothing of scheduling that time around community science events.

In an attempt to claw some of that time back, I began researching new ways we could engage with old hobbies when I noticed an interesting trend: Inventive scientists and tinkerers were using consumer technologies to not only help people get into fascinating hobbies but connect them seamlessly with genuine scientific research. As luck would have it, one such project, called Haikubox, spoke directly to my family’s love of birds.

A box for the birds

Haikubox is the brainchild of David Mann, an expert in bioacoustics who taught at the University of South Florida where he studied the aquatic vocalization of fish and other marine life.

In 2019, he was approached by Holger Klink, a director at Cornell Lab, about producing a bioacoustics product for consumers that mirrored the passive acoustic monitoring (or PAM) used by scientists to research biodiversity and animal behaviors. Mann built a prototype using a Raspberry Pi single-board computer and worked with a grad student in Germany to code an AI neural network that identifies bird calls. With that, Haikubox was hatched.

“Data, science, and wanting to know how the world is and using sound to do that. That drives all of what we do,” Mann tells Freethink.

The Haikubox app shows an entry for the American goldfinch, the state bird of Washington.

Here’s how it works: Once set up outside, the Haikubox uses a microphone to listen for bird calls in the area. Each chirp, trill, tweet, and squawk gets recorded as a spectrographic image. That image is then analyzed by the AI, which has been trained to recognize specific patterns in the soundwaves. Once the AI makes a match, an entry is created and uploaded to the app. Over time, users build a catalog of all the birds that have visited their neighborhood, and with each entry, they can also learn about the species, listen to the recorded bird call, and explore where other users are hearing the bird throughout the network.

Mann and Amy Donner, Haikubox’s business development, provided my family with a Haikubox to try, and we’ve appreciated starting our days with a survey of yesterday’s bird visitors. Most mornings, we’re greeted by the usual suspects: dark-eyed juncos, Steller’s jays, Anna’s hummingbirds, and enough black-capped chickadees to star in a straight-to-streaming Hitchcock ripoff.

But we’ve also been pleasantly surprised by many unexpected visitors we would have otherwise missed. A migrating American goldfinch. A rare pileated woodpecker. A talkative barred owl (who, we later learned moved, into the copse behind our apartment). Even with our busy schedules, we could learn about our environment in the time it takes to savor that first cup of coffee.

“We’ve lived in Florida for 20 years. There were birds it was picking that I didn’t know were there,” Mann says. “It changed how we interacted even when going for walks with our dogs. We were listening the whole time and looking up in the trees for what was there.”

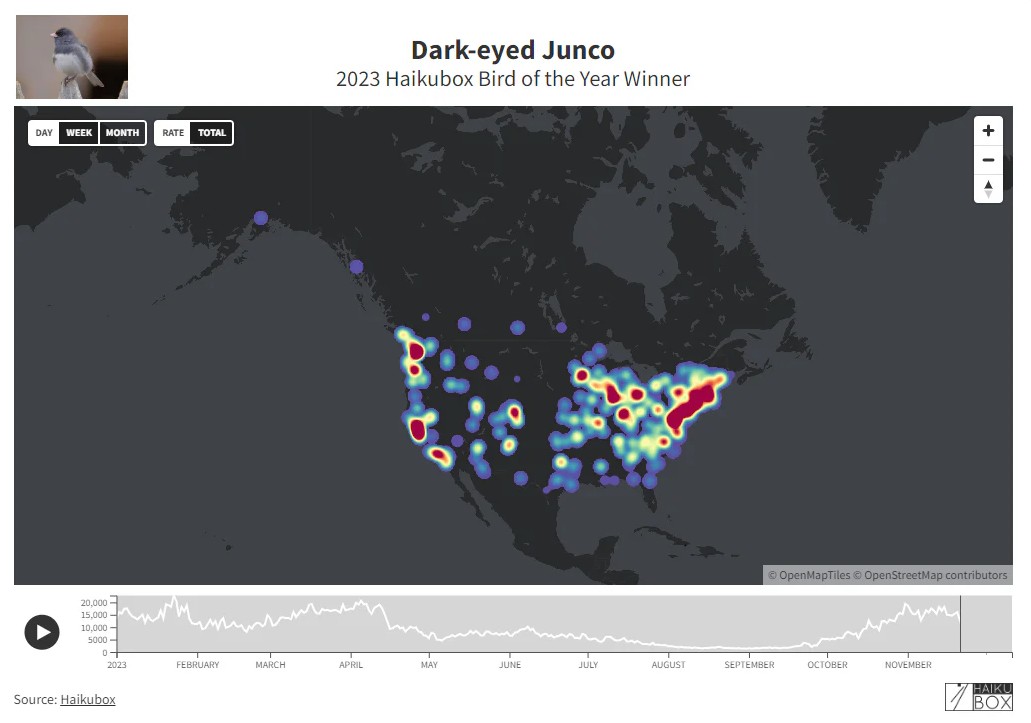

An interactive heat map visualization of dark-eyed junco identifications. The data shows the species migrating to the southern U.S. for the winter.

Each recorded call also goes into a cloud-based database for future scientific research. To date, Mann and his team have collected more than 800 million recordings across the US.

They are also using the data to perform their own research. Collaborating with researchers at Cornell Lab’s K. Lisa Yang Center for Conservation Bioacoustics, they analyzed Haikubox data captured during the April 2024 solar eclipse to see how the path of totality affected bird activity and vocalizations. As of our interview, they are submitting their findings to scientific journals for consideration.

“It’s a joyful thing, birding,” Donner says. “It’s not political. It’s very different from a lot of other stuff going on in the world. People can have unifying conversations about birds and their birds.”

Leveling up science

But birding isn’t the only hobby getting the community science connection. With a little creativity and ingenuity, it seems, most any hobby can contribute — including video games.

In 2020, Massively Multiplayer Online Science, an initiative to connect video games with research, teamed up with Gearbox Software, McGill University, and the Microsetta Initiative to create a video game. More specifically, a mini-game called Borderlands Science, accessed through Gearbox’s Borderlands 3.

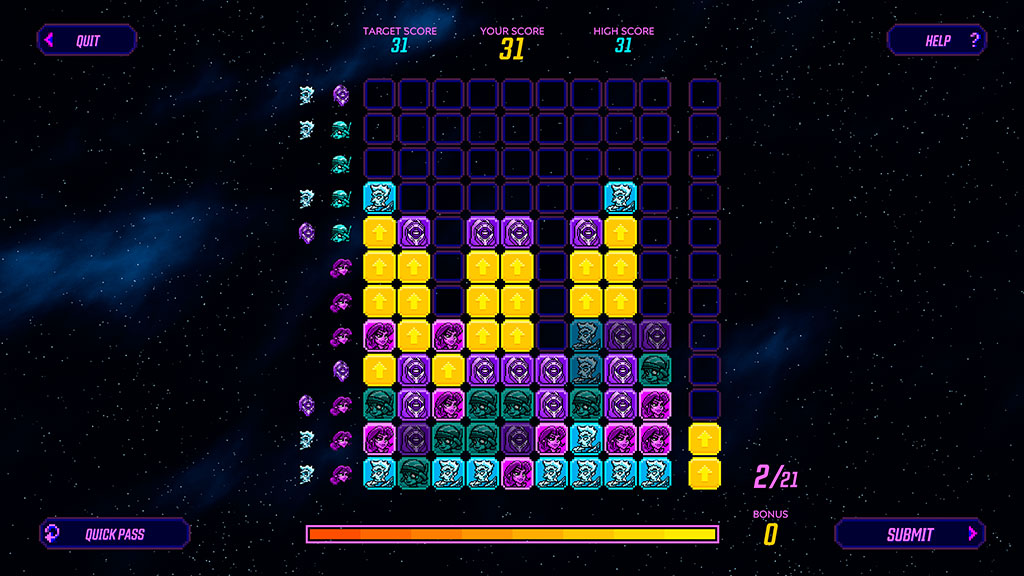

The game was a block puzzler, in the vein of Tetris. You know the type: colored blocks need to match up, lines need to disappear, and high scores need to go higher. Classic stuff. The science all happened under the graphical hood. By simply playing the game, players helped fix errors commonly found in genomic sequencing data.

You see, when researchers sequence genomes, they typically decode small chunks individually before mapping them back together. However, this method can introduce errors. What technology is used, how repetitive the genome is, and inaccurate variant identification all affect the data. When the chunks are mapped back together, a genome’s nucleotide bases — the As, Cs, Gs, and Ts of DNA — can accidentally be substituted, deleted, and even overlapped.

A still image from the Borderlands Science game. Players solve alignment problems found in genomic sequences by lining up specific block combinations.

Borderlands Science took a dataset of 953,000 rRNA fragments from non-human gut microbes (each roughly 150 nucleotides long) and transformed small sections of these genomic sequences into block puzzles. When players played the game — by moving colored blocks to remove spaces and lining up specific combinations — they also removed errors from this dataset. An AI would then compare multiple player solutions to each puzzle and extract the optimal ones, which allowed researchers to align the sequences more accurately.

“Alignments are always ‘messy’ to a degree since they include the information that comes from millions of years of evolution,” the McGill researchers write, “but the information we get from players appears to have the potential to improve these alignments.”

And players never felt like they were doing tedious data-management work. They just had fun playing a game — and received some in-game currency for Borderlands 3 as a bonus.

In a 2024 paper detailing the results, the researchers noted that more than 4 million players played Borderlands Science and helped to solve more than 135 million of the sequencing problems. Their solutions will help scientists access better data, which in turn will help them understand the evolutionary history of these microbes as well as how they may affect people’s health.

“We spend billions of hours playing video games every week. With the largest online game — World of Warcraft — people [have] spent more than 6 million years,” MMOS writes on its website. “Converting a small fraction of that time will be a powerhouse for scientific research.”

As part of the Active Astroids project, citizen scientists search images to discover new asteroids with comet tails, like the one pictured here. The aim is to better map the distribution of water in the solar system.

It takes a village

If birding and video games don’t speak to you, no problem. These are just two examples that inspired me, but there’s a growing fraternity of tinkerers, DIYers, and enthusiasts finding transformative ways to use hobbies to improve the world in small, but impactful, ways. They have found ways to integrate community science with hiking, astronomy, and health and wellness. For some, community science is the hobby.

And the thing about hobbyists is that they are always looking for ways to bring in new enthusiasts. You simply need to discover what interests you and reach out to someone.

As Donner says, “Lifelong learning, you just can’t give that up. You’re never too old to learn something new or make something or give back. This is a ridiculously easy way to do that.”

This post was originally published on here