“I’m a horrible recluse,” chuckles James Oswald, framed at his sturdy kitchen table by an enormous picture window overlooking the Tay.

“I don’t go away from here, really. I have everything I need.”

By “here”, Fife farmer and bestselling crime author James is referring to his stunning, self-designed farmhouse, wedged at the foot of Norman’s Law and looking out over to Errol.

And by “everything I need” he means his study, his dogs (Dogmail and Taylor), his fold of pedigree Highland cows, and his partner of 35 years, Barbara Mclean – whose surname, eagle-eyed readers will note, is shared by the author’s most famous character, Inspector Tony Mclean.

But more on Tony later.

Gazing out the towering wall of windows, rivalled only by a wall of plants (Barbara’s) and another of books (James’), it’s easy to see why the 56-year-old wordsmith never leaves.

I wouldn’t either. And I certainly wouldn’t starve.

Like some Grimm fairy tale, shiny red apples litter the kitchen counter, and a table in the living room is laden with various tomatoes, pumpkins and peppers.

“I made this giant apple pie yesterday,” James says, pouring a pot of tea into a clear, Scandinavian-looking teapot. (The pie is the size of of a serving tray, and about 4 inches deep.)

“My brother lives just up the hill in our parents’ old house, and the orchard is just overflowing.”

Tragedy brought James Oswald to farm

It’s an idyllic scene – the mist rolling up against the glass, the logs stacked on the fireplace, Barbara re-upholstering a chair in the back room while James and I talk.

But before this house was built, when James first returned to Fife, things looked very different: Barbara in Wales, James and the dogs in a caravan on the farm, and a stack of half-written books leaning against the closed door of his imagination.

It was tragedy that brought James and his siblings back to the farm in 2008 when their parents, who owned the farm, died suddenly in a car accident.

James had just begun writing a book about a 12-year-old girl who comes back to her Cupar home to find her parents have perished in a fire.

“How do I put myself in the mind of a 12-year-old girl?” he muses, on one of the many tangents of our meandering conversation.

“I just think about it. What would be important to her?

“I wish more men thought about women’s lived experiences, because then maybe we wouldn’t be so s***** to women.”

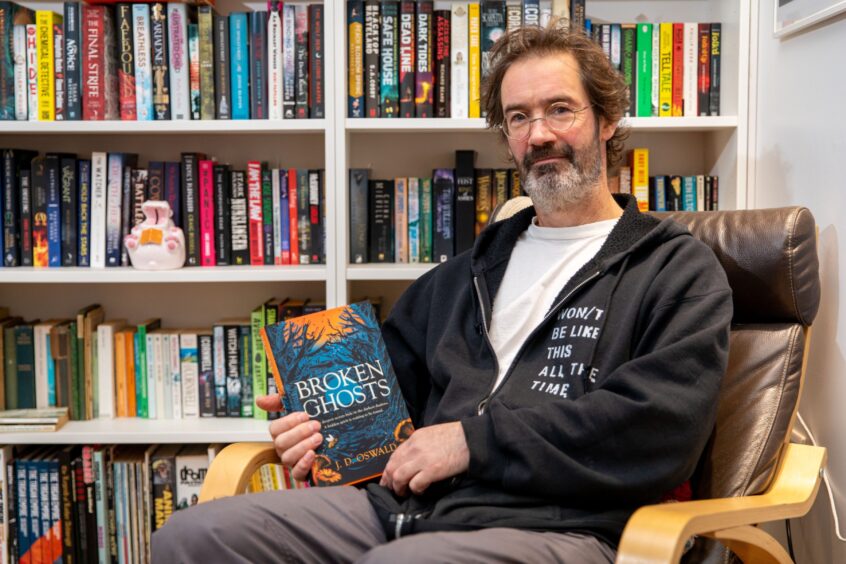

That book would go on to become standalone novel Broken Ghosts, released earlier this year – 16 years after he began writing it.

But at the time, his parents’ untimely death knocked the wind out of James’ sails entirely.

“It killed my creativity, and it killed that book in particular, stone dead,” he recalls. “I stopped writing for about two years, and my siblings and I divided up the farm.”

Fife farm was father’s Christmas wish

Though not from Fife – he was brought up in the south of England, and carries a gentle English accent in his soft-spoken voice – James had spent a lot of time on the farm during his time studying psychology at Aberdeen University.

“When I was growing up, my dad worked as a stockbroker in London, but all he ever wanted was to farm,” recalls James.

“We had this little book that we’d write our Christmas wish list in every year, we each had a page.

“And dad used to just write ‘farm’ on his page every year. Eventually, in his 50s, he did it – took the wad of cash his firm gave him and bought this place.

“He farmed it until he died, and I would help him out during university.”

Books make ‘a lot more money’ than farm

It’s this sentimental attachment to the farm – and a self-confessed stubbornness at being told he “couldn’t” keep it going – which moved James to keep the farm after his parents’ death, rather than sell it off entirely.

Although he admits the farm is not what’s paid for his impressive pad.

“It is a little bit profitable, but not very,” he says matter-of-factly. “We had to sell most of the arable land so I could buy out my older brother and sister.

“The sheep and their fields are now owned by the neighbours. And my younger brother got the old house.

“The books make a lot more money than the farm does!”

Inspector Mclean set for grisly festival case

Indeed, James famously made waves in the publishing world after going from a self-published novelist, giving his first book away from free on Amazon, to becoming an acclaimed author on major publisher Penguin’s roster in just a few short years.

He’s just finished the edits for his 14th Inspector Mclean book, The Rest Is Death, and admits he’s “relieved” to be done with that part of the process.

But eager readers will be delighted to know he’s already getting started on book 15.

“I don’t want to give too much away, but it’ll be set during the [Edinburgh] festival,” James says. “Summertime. I’ve done too many winter books, so I’ll do a summer one. It’ll still be nasty and gruesome and grizzly, obviously.

“But I don’t have much in the way of plot yet. I almost never plan anything, I just start with a crime and work it out from there, like my inspector would.”

Stuck on a sentence? Take it to the coos

And like any investigator, James regularly runs into problems or puzzles he can’t solve during his writing process.

That’s where the cows come in.

“I’ve got a fold of 16 Highland cattle just now,” says James, pointing out the window. A giant, hairy bull and a few of his sons are chewing contentedly in the fog.

“It’s called a fold when it’s Highlands, not a herd. I don’t know why,” he observes. “But I chose Highlands because, despite their appearance with their big horns, they’re very placid.

“Public paths run all through this farm, and I would hate for someone to get hurt, so I’ve worked to breed a laid back fold. If any of the bulls or the heifers are aggressive, I stop breeding from them.”

Whenever James runs into a plot hole or character issue that he can’t work out on his rotating whiteboard (very Criminal Minds), he takes it to the coos.

“If I’m stuck with a bit of writing, I just go up there, get the brush out, start brushing and let my mind wander,” he says.

Writers are notoriously sentimental, but farmers can’t afford to be. Does James ever struggle, when it comes to parting with the cows he’s spent so much time bonding with?

“It is hard,” he admits. “The four born the year before last – Keir, Kenneth, Keith and Keev – are all going to the abattoir next week.

“But that’s what they’ve been raised for, it’s what farming is. And I do love beef.”

What counts as luxury for reclusive writer James Oswald?

Though it sounds a charming life, James’ days are filled with hard graft. Icy mornings in the fields, then up to the study to bash out words.

And on a farm, days off are few and far between.

So what does the author do, in this reclusive bubble, when he’s looking for a little indulgence?

“I like tinkering with old cars,” he says. “I have a 1967 Alfa Romeo Spider tucked away in a shed which I have badly restored. It needs a paint.

“And an old series three Land Rover which I’ve stripped and I’m going to convert to electric.

“And!” he adds, the most animated he’s been all day: “I have an expensive coffee machine.”

It gleams on the countertop, pride of place. Everything a writer needs.

Broken Ghosts by James Oswald, published by Wildfire, RRP £20, is out now.

This post was originally published on here