LAHAINA — As Roland Tanner rolls through his Wahikuli neighborhood in his 2015 Tacoma pickup, he is greeted by residents who are grateful he is still patrolling their streets.

Soon after the August 2023 wildfire destroyed much of Lahaina, including many homes in Wahikuli, Tanner began planning a neighborhood crime watch program. Patrols started just days after the area opened to its residents on Sept. 3.

The program’s primary purpose is to prevent looting, mostly of building materials and tools left overnight. But it also has been to prevent a phenomenon known as disaster tourism, where visitors gawk and take pictures of destruction for social media.

One such incident occurred three weeks ago in another area of the burn zone, when a group of tourists were stopped by Maui police for taking pictures of the famous Lahaina banyan tree on Front Street that is in a restricted area with hazardous debris.

“It’s all about social media and getting the likes,” said longtime Lahaina resident Laurie DeGama, a member of the mayor’s advisory committee and president of the Parents Teachers Students Association at Lahainaluna High School.

She was displaced by the fire that also caused the death of her uncle Richard Kam, for whom she was a caregiver for 20 years.

“For me, it is not being against tourists because it can be locals, too,” she said. “It is people in general not being respectful of the area.”

DeGama cited a realtor who posts YouTube videos that show how to enter the downtown area burn zone via Shark Pit or Lahaina Shores to get to Breakwall, a surf spot.

“He shows how to get there and he says ‘I don’t know why the town is still blocked off,’” she said. “Like, isn’t it crazy? He’s showing them how to go to get there and it’s horrible. So, he’s part of the problem.”

Maui was remarkably successful in blocking off the problem of disaster tourism in Lahaina, according to After The Fire CEO Jennifer Gray Thompson, whose organization was born after she survived a massive fire in the North Bay Area of California in 2017.

“Amazing, I’ve never seen that before, ever, in any fire,” Gray Thompson said. “We were the first ones out of the gate in 2017, like the big, massive, 8,900 structures (destroyed). People from all over got in their cars and watched fire victims as they cried over their previous lives. They looted and stoled from what remained in the ashes.”

More than 30 Maui County officials attended After The Fire’s Wildfire Leadership Summit in September.

“There’s no way around the fact that it is just a slog, it’s really hard, it really takes a long time,” Gray Thompson said. “You guys are ahead of where they told you you guys would be. We didn’t have holy, ancient burial grounds below our homes, at least that we acknowledged. … I think Maui officials have done a good job.”

To keep people out of the burn zone, including for their own safety, the Maui Police Department got a lot of help early in the response by other agencies, including the Hawaiʻi Army National Guard, which at one point was staffing 21 entry control points.

Now, the Lahaina patrol division captain for the police department is actively overseeing and monitoring patrol efforts throughout the affected areas with a minimum of five officers and one supervisor on duty at all times, according to MPD.

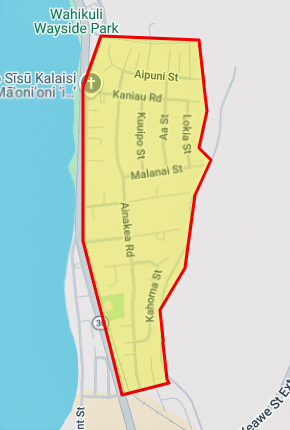

Between Sept. 3 and Nov. 12, officers conducted 31 beat checks within an area spanning Wahikuli to the edge of Lahaina Cannery Mall. During the same period, 38 calls for service were received, resulting in 15 documented incidents, which include an unattended death, a trespass report, disorderly noice and a report of family abuse.

After the incident at the banyan tree, the Maui Emergency Management Agency set up a checkpoint on the beach near Kamehameha Iki Park. There already was a nearby checkpoint on Front Street to the beach, but MEMA figured out the access into the restricted zone was coming largely from a beach path next to Lahaina Shores.

Kono Davis, the operation coordination section chief of MEMA, said this new checkpoint has been effectively stopping disaster tourists and others from accessing the commercial part of Lahaina that is still being cleared of debris.

Two guards with Aegaeon Security, the company contracted by Maui County, are stationed there for 12-hour shifts daily. Ten other checkpoints around the 5-mile burn zone are still in place and guarded around the clock. Access is granted to only people who have placards or official business.

A guard at the new checkpoint, who did not wish to be identified, said an average of about 15 to 20 tourists per day approach the area, but are understanding when they are told why they cannot enter the restricted area.

The guard also said local and tourist surfers are understanding when told they must paddle about 100 yards to Breakwall, a very popular surf break, instead of walking along the beach.

Before the new checkpoint, Davis said, “Everyone was coming through. You’re on the beach (that) goes all the way up to Lahaina Harbor.”

This now is one of the few areas that still remains restricted more than a year after the fire.

Gray Thompson said that the interest in Maui is “going to fade off, so you are going to get some people who come back for the 18-month mark, for the 2-year mark.”

She said more can be done to alert people, including an informational campaign that would welcome tourists back to Maui but explain “in the nicest way possible” to be mindful and not gawk at people’s pain.

Gray Thompson also recommended installing wildlife cameras around the burn zone that is still not opened to non-residents.

“I would be prepared for people to encroach more,” she said. “Some of them will have bad intentions. Most won’t, they’re just very curious. Maybe they’ve been coming there for years and they feel the loss. If they want to do this, maybe they could organize it so it is just one hour per week where they could walk through respectfully and guided and learn about the history. … One way you can harness it is to educate it as you go because people will find a way there.”

The burn zone originally was divided into 101 zones. Now, 19 remain to be cleared of debris. They range from Shaw Street north to Kenui Street and everything below Honoapiʻilani Highway.

After Tim Putnam’s house burned and his income of 41 years as a fisherman and charter boat captain abruptly ended with the fire, he went to work for Aegaeon Security with a post at the intersection of Kaniau Street and Honoapi’ilani Highway.

“I’m able to help protect Lahaina and help educate tourists that come here who are not aware of the total situation,” he said. “I try to take time to explain what’s going on, where they can and cannot go. And nearly everyone of them has been respectful to me and grateful for the information I give them.”

Tanner patrols as a volunteer in the late afternoons following his day job as a painter at Kaʻanapali Beach Hotel. Despite the fire burning all three homes on his Fleming Road property, he has missed only three days of duty. He also has help from neighbor and longtime Lahaina resident Earle Kukahiko, and his daughter and her boyfriend.

Tanner stops at four to five security checkpoints that are in place to limit access to the burn zone that still needs cleanup. He chats with the guards, waves to neighbors who are out for walks and makes sure his presence is known. He’ll greet people he doesn’t know to see what they are up to in parts of the neighborhood that are still recovering.

Tanner goes to his rental home in Kahana before returning to his old neighborhood for a night patrol, with an orange light on the top of his truck to let neighbors know he is helping to keep them safe. He points out that most of the burn zone desperately needs new street lights.

Tanner said more help is needed from residents who have the time. He also is also grateful the Maui Police Department have increased patrols through the area, especially at night.

He has documented nine incidents among the intricate notes he keeps on his phone, including an incident on Oct. 16 when he saw a man wielding a machete and shouting threats. Tanner stopped to talk the man to calm him down, and he said it worked with no issues from the man since.

On Fleming Road two houses mauka of Tanner’s property, Gene and Joann Milne are nearly done building the ‘ohana unit in the back of the property and hope to be living in it by Christmas. They currently live in a trailer on their property.

The Milnes say the Wahikuli watch program is needed. They try to keep an eye on neighbors’ lots who are not around. They say contractors leave tools and equipment at construction sites, which are bait for looters.

“I think more people involved would be wonderful,” Gene Milne said. “One, because it helps expand our friendships with our neighbors. And we get to know who’s where, and what they’re doing. So even if I’m not on a neighborhood watch (patrolling) and I know the people, I know if somebody’s not supposed to be there. Just if I’m driving by you know that that guy doesn’t live here.”

Milne said he has seen cars he’s not familiar with appear to be scoping the neighborhood at night, when there is little to no light around. One incident he remembered happened during daylight.

“We had a (nearby) incident where a truck pulled up and was loading tools and the workers came out and said, ‘what are you doing?’,” Milne said. “Those guys said ‘So we’re loading up our tools,’ and then it’s like, the workers inside came out and said ‘those are our tools.’ “

Gray Thompson warned against anyone on Maui becoming complacent.

“I’ve walked into 18 counties now across four states for fire and I’ve never seen so much protectionism around the fire (as Maui),” Gray Thompson said. “It’s interesting being on Maui because it’s the most complex fire I’ve worked. It’s the legacy of colonialism over everything, as it should be honored. It’s the island piece. It’s the number of casualties. It’s the fact that everybody in the world cares about Maui in a way they don’t care about most of the places I walk into.”

This post was originally published on here