Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: pulps, spicy history stories

The story behind long running fiction magazine 10 Story Book runs through a number of Chicago newspaper and business institutions.

According to a 1906 overview of the history of fiction-focused periodical publishing in Chicago, the rise of Chicago-based literary story papers such as the Chicago Ledger and the Saturday Blade was fueled in part by the rise of mail-order catalog-based retail giants in that city and their advertising needs. Famous names like Sears, Roebuck and Co. & Montgomery Ward and Co. have their roots in Chicago, but it’s the people behind the lesser-remembered Chicago Mail Order Company that may have had the most interesting and direct impact on periodical fiction publishing history in America. Founder Benjamin J. Rosenthal (1867-1936) and the partners behind that company would soon become involved in a fiction-publishing newspaper syndicate and their own historically important fiction magazines. Chicago Mail-Order Company even became a footnote to comic book history during the Golden Age. That journey began with the Daily Story Publishing Company and the literary periodical 10 Story Book. In later decades, the title became known as part of the spicy pulp category, but it launched with different intentions in mind.

As most of these Spicy History Stories articles tend to do, this piece has spawled well beyond what it was intended to be. The original idea was to dig into the little-documented origins of Sun Publications, best remembered for its tenure in publishing 10 Story Book and the short-lived historical pulp Golden Fleece. But that led to an even more obscure and fascinating tale of the Chicago businessmen who originally financed 10 Story Book, and how that resulted directly in the launch of important fiction magazines Red Book, Blue Book, and Green Book.

And with that, it’s time for Spicy History Stories #6, the sixth installment of a weekly column about pulp magazine history that we’ve launched to coincide with Heritage Auction’s weekly pulp magazine auctions. Unlike other auction-centric posts we’ve done here, this column is not necessarily designed to be closely tied to any particular items up for auction. Mostly, it’s this: if you enjoy the nerdy details of comic book history, you’re going to love the astounding (and yes, sometimes weird) history of the people and companies that made the pulps.

Most histories date the founding of the Chicago Mail Order Company to 1889, the year Rosenthal left Gage Brothers & Co. to launch his own millinery business. Partners Louis Eckstein, Louis M. Stumer, and Abraham R. Stumer joined the firm by 1891. The partners’ initial major business launch was The Emporium in Chicago that year. Various aspects of the partnership businesses then evolved to include Chicago Mail Order Company by the turn of the century, while the partnership firm of Stumer, Rosenthal & Eckstein also became involved in other retail businesses, restaurants, and real estate endeavors in Chicago. The North American building in Chicago is one of their most historically famous development projects.

The Daily Story Publishing Company

Benjamin J. Rosenthal’s acquaintance with Chicago Inter-Ocean and Chicago Tribune newspaper reporter Dwight Allyn would lead the partnership down the pulp publishing path. A veteran reporter whose experiences as a field correspondent and press connections in Chicago left him well familiar with newspaper syndicate operations, Allyn launched the Daily Story Publishing Company with $5000 worth of backing from other sources in November 1899. Allyn’s operational partner and first editor at the company was a veteran reporter with deep ties to Chicago’s literary scene, James S. Evans. Evans had made a mark as a reporter in a number of states before coming to national notice for his coverage of the 1892 U.S. presidential campaign for the New York Sun. In Chicago, Evans had worked as a literary agent as well as contributing serial fiction to the Chicago Tribune. His time at the Daily Story Publishing Company was short-lived, as he had returned to reporting by 1902, this time for the New Orleans Times-Democrat.

The idea of the Daily Story Publishing Company was to syndicate fiction instead of news or more general material to daily newspapers, in an era when such fiction in newspapers was common. Literary syndicates were not a new concept in 1899, but they were still in their relatively formative early years in America. Technical advances in the American rail network and printing technology over the period of 1860-1900 resulted in an explosion in demand for cheap fiction and periodicals that printed fiction to satisfy that demand. Story papers, quarto libraries and weeklies, and other dime novel fiction-focused periodical formats were on the rise, and so were the number of news, magazine, and general interest formats that included or featured fiction. This included newspapers, which commonly included some fiction. According to Fiction and the American Literary Marketplace and the Role of Newspaper Syndicates in America, 1860-1900, by Charles Johanningsmeier, the number of daily newspapers in the U.S. increased from 387 to 2,226 over that period. This gave rise to increasing expectations about content from newspaper readers, which in turn caused the rise of newspaper syndicates that could provide fiction.

While various methods of syndication had been done in some specific circumstances prior to the 1860-1900 period, Ansel Nash Kellogg‘s use of the method that came to be called “patent insides” or “readyprint” beginning in 1861 came at the right time to gain traction. Kellogg moved to Chicago and started the A. N. Kellogg Newspaper Publishing Co. in 1865, becoming a significant force in newspaper syndication’s early years in America. Using this method, a portion of a newspaper could be printed at a central location and then sent by rail to the publisher for printing their local content. This gave way to syndicates sending stereotype plates to client newspapers as well. Per Johanningsmeier, some syndicates also offered the availability of galley proofs of their material to target larger papers after the rise of Linotype machines in the late 1880s. This method would also become useful for fiction-focused syndicates due to the smaller amount of material they sometimes offered.

Serializing Fiction in the Victorian Press by Graham Law notes that fiction syndication to newspapers began to scale up in the UK in the early 1870s with the efforts of William Frederic Tillotson and his Newspaper Fiction Bureau in England. Tillotson had entered the U.S. market by the early 1880s (which offered specific operational challenges for foreign authors both before and after the Copyright Act of 1891), while Johanningsmeier speculates that Tillotson’s 1884 visit to America spurred a number of U.S. firms to syndicate fiction. These included newspaper-operated syndicates such as the New York Sun, and the Boston Globe, as well as Samuel Sidney McClure‘s Associated Literary Press. Closer to home for Dwight Allyn and the Daily Story Publishing Company, the American Press Association was founded in Chicago in 1882, and by the time it began including fiction in its offerings in the early 1890s, it was one of the country’s dominant syndicates.

Despite the competition in this niche, the Daily Story Publishing Company seems to have found its footing in its early days of operation in the first half of 1900. Evans’ connections to American authors and within the newspaper industry around the country seemed to make for a potent combination.

American Press Association v Daily Story Publishing Company

But trouble emerged for Daily Story from the outset. Within the first few days of operations in January 1900, one client paper, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, published Daily Story material without its copyright notice as they were contractually required to do. Notice of copyright was required by the copyright law of that era in order to benefit from copyright protection, and it was common practice for newspapers and syndicates to crib material that was not copyrighted. Believing the story to be fair game, the American Press Association syndicate lifted it for distribution to its own client newspapers.

This type of situation was an existential threat to Daily Story, or many such syndicates for that matter. Full-service syndicates such as the American Press Association usually sent out material in the form of stereotype plates, thus sidestepping this potential problem, but with its short fiction-only focus, Daily Story was not in a position to do that. This meant they had to rely on their many client newspapers to correctly fulfill this requirement.

In October 1901, Daily Story sued the American Press Association for $2,000, alleging copyright infringement, and also stating their intention to sue American Press Association clients. The American Press Association countersued in an attempt to keep Daily Story from going after their clients. They maintained they had a right to syndicate the material due to the lack of copyright notice in one paper, and sought to prevent Daily Story from seeking damages from its client newspapers. In early June 1901, the court decided in Daily Story’s favor, determining that St. Louis Globe-Democrat‘s error did not invalidate Daily Story’s copyright protection. The case was appealed, but the decision was ultimately upheld. It became part of a larger struggle during this period to clarify copyright issues surrounding syndicated content in newspapers (see also Tribune Co. of Chicago v. Associated Press, 1900).

The 10 Story Book Experiment

Despite the legal wrangling, Daily Story’s fiction syndication business continued to build its list of client newspapers during 1901, and plans were made early that year to spin off the stand-alone periodical 10 Story Book. The concept in theory was that 10 Story Book would contain fiction submitted to Daily Story that was unsuitable for newspaper syndication.

The original group of Daily Story backers had been anchored by Chicago lawyer and investor Louis M. Cahn, but the developments of 1901 and the launch of 10 Story Book would require more capital. Stumer, Rosenthal & Eckstein bought stock in the company and may have bought out the original investors entirely. The exact timing of this investment in 1901 is not clear, but shortly before or after the debut of 10 Story Book is most likely. The first issue hit the streets of Chicago within days of the American Press Association v Daily Story Publishing Company court decision, and they were launching the title without advertising or a distributor.

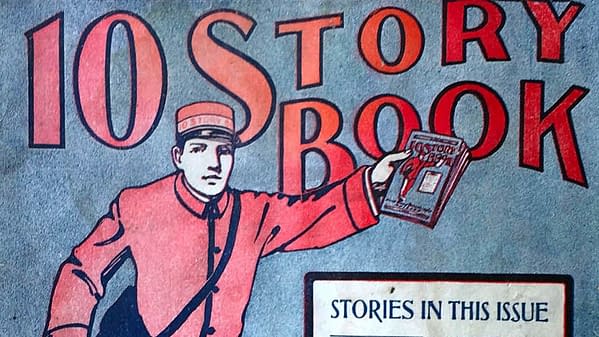

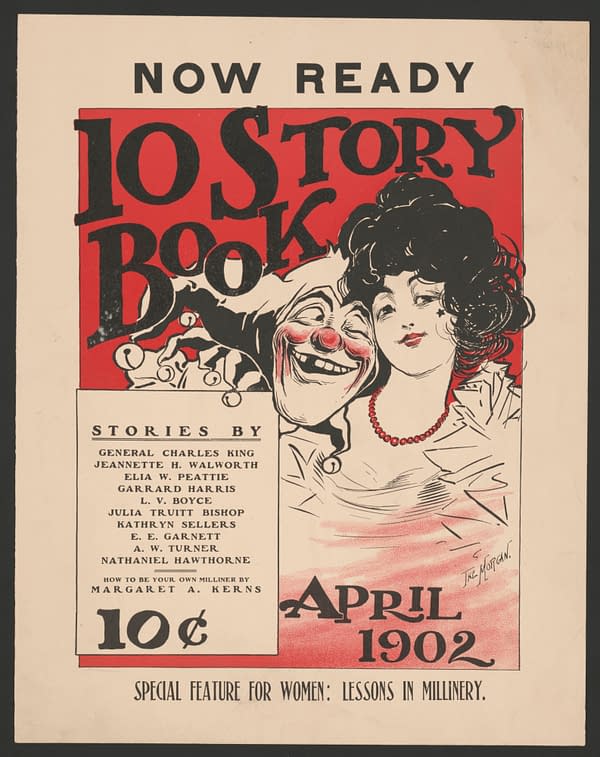

In Magazines of a Market-Metropolis: Being a History of the Literary Periodicals and Literary Interests of Chicago, a dissertation done at the University of Chicago in 1906 by Herbert E. Flemming, the launch of 10 Story Book is chronicled in some detail: “The first issue of 10,000 was tried on the Chicago public exclusively. The story-books were placed in the hands of sixty boys fitted out in striking red coats and white trousers [author’s note: these uniforms would seem to explain the artwork on the earliest covers]. The boys hawked them from the street corners in the loop district until stopped by the police. But that was not until sales had proved Chicago to have in its population a large class of people interested in smart stories. The Western News Co. called on the publishers for further issues, a post-office entry was made, and the Daily Story Publishing Co. began the periodic publishing of the 10 Story Book for the general fiction magazine market.”

Editor James S. Evans described the type of material Daily Story wanted for newspaper syndication in a letter to the Weekly Clarion-Ledger of Jackson, Mississippi in December 1899, noting that “The Daily Story Publishing Company is in the field for buying short romances — little love stories that will appeal to women and young people. The articles must be clean, free from giving offense to any race, religion, sect or denomination, and must be kept in 1400 words.”

But it would appear that Daily Story made the decision relatively early on to accept some types of submitted stories outside of those parameters, or to seek them out. As Flemming notes from his 1906 perspective: “In its attention to the unique, weird, and bizarre subjects and the mystery in detective tales the 10 Story Book was at first regarded as an imitation of that periodical ‘devoted exclusively to original, unusual, fascinating stories’ published in Boston — the Black Cat. But through the years it has budded some offshoots from the main branch of studied originality. ‘An emotion with every story’ is one of the mottoes of those directing the periodical. While the stories are not indecent, the manager frankly says that he is not squeamish. Although the stories are not positively risque, in many of them sexual passion provides the theme for human interest.”

Given that the name of 10 Story Book publisher Daily Story Publishing Company was so similar to Black Cat publisher Shortstory Publishing Company’s name that they were sometimes confused, it’s hard not to wonder if this was the target from the very beginning of the company. But both 10 Story Book and Black Cat, among other booklet-format literary periodicals, were inspired in part by The Chap-Book (1894-1898), founded by Harvard students Herbert Stone and Ingalls Kimball. Stone & Kimball moved to Chicago in August 1894, where Herbert’s father Melville Elijah Stone had founded the Chicago Daily News. Melville Elijah Stone also became the general manager of the Associated Press in 1893. The business story behind The Chap-Book would have been well known to Chicago newspaper figures Allyn and Evans.

Chicago historian Edward Sharp in Magazine Publishing in Chicago notes that in that city alone The Chap-Book inspired imitators including Blue Sky (1899-1902) and Four O’Clock (1897-1902) before the launch of 10 Story Book, and many more nationally. Nevertheless, 10 Story Book would soon carve out its own unique identity and attain early success in the process.

Red Book’s Origin Story

Allyn’s deal with Stumer, Rosenthal & Eckstein came with an expiration date. He had the option to buy the stock back by the end of 1902. Flemming suggests that 10 Story Book did well enough in its first 18 months of operation that Stumer, Rosenthal & Eckstein had realized “a small but neat profit on their investment” and offered to buy Daily Story Publishing Company outright and put Allyn on salary. Allyn rebuffed this offer and bought the stock back per the agreement. Evans left the company around the same time.

But Stumer, Rosenthal & Eckstein decided they liked the literary magazine business, and would stay in it without Allyn and Daily Story Publishing Company. Looking for a managing editor, they reached out to Charles M. Faye, who was Melville Elijah Stone’s managing editor at the Chicago Daily News. Faye himself was in the process of launching another magazine, The World To-Day, but suggested Chicago Daily News correspondent, Trumbull White would fit the role. Of course, this would lead to the launch of the legendary title Red Book and much more. We’ll discuss how this played out next time.

Stay up-to-date and support the site by following Bleeding Cool on Google News today!

This post was originally published on here