“Kick me,” says Bruce Lee, dappled by the light of a tree while giving a martial arts lesson in an idyllic garden. The nervous teenager standing opposite kung fu’s greatest icon in Enter the Dragon (1973) is Stephen Tung Wai, who was brought on to the production by his former Peking Opera school classmate, the stuntman Lam Ching-Ying, who would later star in Tung’s directorial debut Magic Cop (1990).

“Lam Ching-Ying had worked with Bruce Lee on The Big Boss [1971], and after he came back he was full of high praise for Bruce,” says Tung. “Lam Ching-Ying and I shared the same master; he was my senior, and I was shocked because I’d never heard Lam Ching-Ying praise someone like that before. At the time, I didn’t know that working with Bruce Lee would turn out to be so significant, but after Bruce Lee passed away, I felt lucky to have done a scene with him. It was only one day of shooting, but because of that scene, people remember me, so I feel very lucky.”

If Tung had never made another film, that 1973 kung fu lesson would have assured his place in movie history, but Tung has become one of Hong Kong’s most acclaimed action choreographers. In Herbert and Albert Leung’s new film Stuntman, art imitates life as Tung plays Sam Lee, a former action coordinator who quit the industry after an accident on set left a stunt double paralysed. Coaxed out of retirement by a director (To Yin-Gor) making his swansong, Lee’s old-fashioned, risk-anything-for-the-shot style clashes with the production’s star, a former member of his team, Wai (Philip Ng).

Like Jackie Chan and Sammo Hung, Tung belongs to the generation of filmmakers who joined the industry from the world of Peking Opera, having studied at Fen Ju-Hua’s Spring and Autumn Drama School in Hong Kong. “When I was younger, Hong Kong’s economy was not that good, so no matter if kids were naughty or not, their parents would consider sending them to the Peking Opera school,” he says. “In that era, most of the well-known stars were from Peking Opera. Nowadays, Peking and even Cantonese Opera are dying arts, they’re not as popular as they were.”

In Stuntman, Sam Lee is unyielding in his drive for perfection, but Tung’s career has been defined by adaptability, spanning kung fu and wuxia cinema to gangland bloodbaths and arthouse fare. In the later 1970s, Tung had the good fortune to travel to Taiwan to work alongside one of the most influential choreographers in the business, Han Ying-Chieh, whose credits included Lo Wei’s The Big Boss (1971) and Fist of Fury (1972) starring Bruce Lee, and King Hu’s wuxia classics Come Drink with Me (1966) and Dragon Inn (1967).

“I was very young, transitioning from a child actor to a stuntman, and Han was a very experienced Peking Opera master,” says Tung. “At the time the action style was very different because it was more like the stage, theatrical style. My first trip to Taiwan was arranged by Han. I went there with Lam Ching-Ying and Yuen Biao. Han preferred working with us because it was easy for us to communicate as we all came from Peking Opera. We learned a lot from Han. We were all so green back then.”

Back in Hong Kong, Tung co-starred with Sammo Hung in Joe Cheung Tung-Cho’s kung fu comedy The Incredible Kung Fu Master (1979) and had featured roles in several martial arts television series. However, kung fu fell out of fashion as the 1980s rolled on, and Tung helped drive the shift from period martial arts movies to a contemporary action cinema when he served as action choreographer on John Woo’s ‘heroic bloodshed’ masterpiece A Better Tomorrow (1986).

Tung says working with Woo, “truly inspired me. At that time, there were not many Hong Kong films with gunfights, and Woo’s treatment of the gunfights and the drama was so good.” He describes the experience as, “like a lightbulb went off in my head, the way that John Woo built up the tension,” noting that Woo wasn’t alone in developing the action film in the 1980s. “There are other directors, like Sammo Hung with The Prodigal Son [1981], where he mixed comedy and drama within the action and hence built up a stronger sense of tension in those scenes. These were like nutrients that made me grow more mature in my knowledge of making action movies.”

Tung’s maturation has been evident in his subsequent success – he’s won best action choreography at the Hong Kong Film Awards seven times, a feat equalled only by the Jackie Chan stunt team. And he’s earned the respect of his peers, with the veteran master Lau Kar-Leung trusting Tung to take over his duties on Tsui Hark’s Seven Swords (2005).

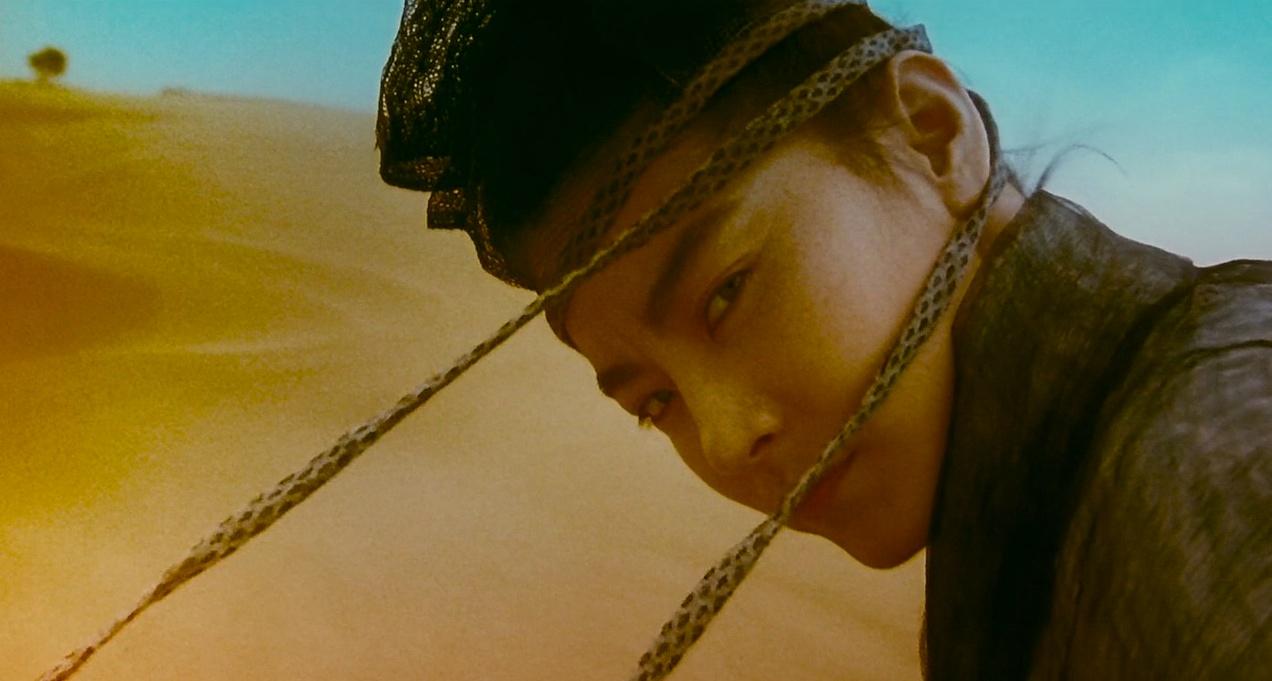

“Lau Kar-Leung sifu passed me the baton because of his health condition,” explains Tung. “Tsui Hark had a lot of ideas, and he needs someone like me to help him transform the ideas into action. As an example, Tsui might think of doing something with a hand fan, and then we have to think, okay, what kind of action can we do with a hand fan? I did a lot of reshoots for Tsui Hark; for example, at the end of Seven Swords there were two people fighting on a wall and we had to reshoot that scene. Tsui Hark trusted me and gave me the autonomy to do what I proposed, but of course I had to communicate with Tsui and let him know what I was going to do first.”

For comparison, Tung says arthouse favourite Wong Kar Wai prizes originality above everything else. “We would sit together and think about what director A, B, C or D would do and then he’d say, ‘We’re not going to do it that way, we have to throw that style out and think of something new,’” says Tung, who worked with Wong on As Tears Go By (1988), Days of Being Wild (1990) and Ashes of Time (1994).

“With Tsui Hark, sometimes we’d sit together and discuss what interesting things we could do. The process would take much longer with Wong Kar Wai. Sometimes we’d go to a location and everything would change. In Days of Being Wild, when Leslie Cheung’s character is in the train station, my original proposal using a first-person perspective was already a bit abstract, but through Wong Kar Wai’s style of shooting and editing it became even more abstract. Working with Wong Kar Wai, you have to find out what he wants and adapt.”

In Stuntman, Sam Lee rages against the young performers who disobey his instructions, even as he struggles to connect with his estranged daughter (Cecilia Choi). The script positions Sam as part of a vanishing generation, seeking one final moment of glory. Similarly, throughout the conversation, Tung expresses his belief that the modern generation lacks the strong foundation imparted to Tung and his contemporaries by the unforgiving regimes of the opera academies and bemoans the lack of opportunities in the local industry.

“In China they have more productions, and their stuntmen and action actors can gain experience faster than their Hong Kong counterparts,” he says. “It would be very hard for Hong Kong action cinema to get back to its heyday.” Yet despite the recent poor health of the Hong Kong industry, 50 years after his onscreen encounter with Bruce Lee, Stephen Tung continues making movies and winning awards. Following Lee’s exhortation, he’s still kicking.

Stuntman is back in selected cinemas as part of BFI’s Art of Action season. It will be released on Blu-ray and digital in early 2025.

This post was originally published on here