Author Stephanie Saldaña recently spoke at Saint Thomas More Catholic Church in Saint Paul about her book What We Remember Will Be Saved: A Story of Refugees and the Things They Carry. The book encapsulates her conversations in 2016 across the Middle East and Europe with refugees from Syria and Iraq — more than half of Syrians were displaced, and millions of Iraqis were uprooted by ISIS.

In her book, Saldaña shares the stories of people who found a way to save a connection to their past despite losing everything. Many escaped without being able to take anything from their home. “The war introduced me to the terrible goneness of things,” she writes in her prologue.

The people she features, Saldaña says, taught her that even in the face of immense violence and loss, “there is always something small to be carried, some act to be done, and that these little things transform history in ways we only later understand.” She quotes an Arabic saying, “Awal al-shajara bithra” — a tree begins with a seed.

Find a full story about Saldaña and her book here.

Other recommended books:

The Braille Encyclopedia: Brief Essays on Altered Sight, by Naomi Cohn

This lyrical book of short essays is inspired from the author’s alphabetical musings on meaningful words that have moved from visual to tactile because of myopia. She was raised near the University of Chicago with academic parents, “in a nest feathered with words, texts, and books. I am made of words, the organized chaos of text, ant colonies of characters streaming over paper, each letter coalescing into ever greater meaning with its sisters.”

In the author’s note, she writes: “The medical system, doing its best to fix the unfixable, often made me feel like my body and I were a problem, My life got a whole lot better when I focused less on medicine and more on how to adapt, including engaging in vocational rehabilitation, which I experience as empowering me to live fully in the body I had.”

In an essay about Braille she notes that it has been said that more than half of our brain is allocated to processing visual input. “Visual pathways once said eyes crinkling without a smile meant repressed laughter. Thick line along seam of t-shirt meant inside out.”

The passage about Ointment, adjacent to the visual image for O, reads simply: “Something a fly gets stuck in. Unguent, healing salve. Meant to be soothing. A balm. In the medicine cabinet, half-used tubes wait, their emptied ends coiled like scorpion tails. A tube of toothpaste and a tube of ointment feel so similar in the hand. Desenex and Colgate feel so different in the mouth.”

Synesthesia: “How I feel I have seen the orange of an oriole when I hear its jazzy call in the cottonwoods. How the smell of wet acorns makes me feel I see their clever shape, their little shaggy berets atop glossy nuts. How ice smells blue.”

Unseen: “As in mysterious forces at work in the cosmos — gravity, electro-magnetism, love. … As in winter sun, veiled by clouds, unseen anywhere in its brief daily arc above the horizon. When, for a moment, the light breaks through, we snap to attention, like dogs, sniffing the air, sitting up for a treat.”

Core Samples: A Climate Scientist’s Experiments in Politics and Motherhood, by Anna Farro Henderson

This collection of well-written essays is from a long-time climate scientist, and mother, who worked as an environmental policy advisor to Minnesota Senator Al Franken and Governor Mark Dayton. It includes stories from research expeditions in the Bermuda Triangle, an icefield in Alaska, a meteor crater in Ghana, and an FBI laboratory. It seeks to lift up cultural narratives that matter to people in order to spark legislative responses to environmental changes. As the publisher note explains, the book is “a love letter to science and a bracing (and sometimes hilarious) portrait of the many obstacles women, mothers, and people digging for truth navigate,” illuminating “the messy, contradictory humanity of our scientific and political institutions.”

Several essays depict the labyrinth that is the political system. When she was a young mother working for Senator Franken, describing the lobbying issues faced by the general public and legislative staff: “If you go through the Senate’s procedures and add up the potential floor time each year, you can see the math doesn’t add up. There is not enough time for all the issues to come to the floor. We are drowning in problems that need solutions. … Yes, you are right, we could put every drop of our soul into your issue. But we are also concerned about people living without insurance, the rate of veteran suicides, mass extinction of plant and animal species, children who don’t have enough to eat, human trafficking, and national security.”

As a policy aide: “Pollution Control staff bring up how drainage from agriculture not only causes toxic algae blooms but also increases our vulnerability to catastrophic rainfall. Staff from the Department of Agriculture shove the spotlight onto the Department of Natural Resources, which allocates permits that pit the groundwater needs of wildlife against those of breweries, farms, and cities. Staff from the Department of Health raise the need to understand environmental problems as social problems.”

Working with Governor Dayton: “I’ve never seen anyone so disappointed in, and hopeful for, what the government can do. He expresses frustration at the constraints on his ability to improve the lives of Minnesotans: limited resources, divided government, bureaucratic processes, his age, personal conflicts. He cannot save the world alone or all at once. Actualizing change requires the collective. And it requires time — the key power that elected officials lack.”

On the art of negotiation: “The trick to moving negotiations forward was allowing people’s emotions to take up space. Only after this could we talk about letting the river rise higher, adding structures and expense that would reduce how much land the dam flooded. The meetings did not create unanimous consensus, but everyone gave a little. Extremes fell away. As in all negotiations, the resulting compromise satisfied no one, but it offered a way to move forward.”

From Conflict to Convergence: Coming Together to Solve Tough Problems, by Mariah Levison and Robert Fersh

Rise to the Challenge: A Memoir of Politics, Leadership, and Love, by former Minnesota Lt. Governor Marlene Johnson

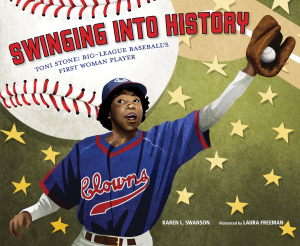

Swinging Into History, by Karen Swanson

This is a children’s storybook about Toni Stone, a Saint Paul woman who was big-league baseball’s first woman player (told in part from Minnesota Women’s Press stories).

Sign up for the new (monthly) Books, Arts & Events newsletter at womenspress.com/subscribe

This post was originally published on here