The grinding trial-and-error process that precedes world-changing scientific discoveries doesn’t really lend itself to dramatization. Instead of our heroes chasing bad guys down dark alleys, the exciting story action involves them standing in front of a blackboard or gazing into a microscope. So dramatic tension is injected by financial or political forces threatening to derail a project of urgent importance (Oppenheimer); the scientists fighting for credibility in the face of belonging to a marginalized group (Hidden Figures, The Imitation Game, any biopic of a female scientist); or the old reliable of the main scientist being a difficult, maverick genius (Oppenheimer again).

Joy: The Birth of IVF, Ben Taylor’s new film out now on Netflix, about the arduous path to develop a viable technique for fertilizing human eggs outside the body and implanting them in the womb, aka in vitro fertilization, hits many of these notes. There’s the irascible pioneer, here played by Bill Nighy at his most crotchety but sympathetic as gynecologist Patrick Steptoe, who introduced laparoscopy to the U.K. He’s teamed with the driven visionary—physiologist Robert Edwards, played by James Norton, who, like Jude Law, is always required to conceal his innate gorgeousness under an unbecoming wig or glasses to convince as an ordinary guy. And together they must struggle against a fusty medical establishment, hostile tabloid coverage, and reactionary religious opposition.

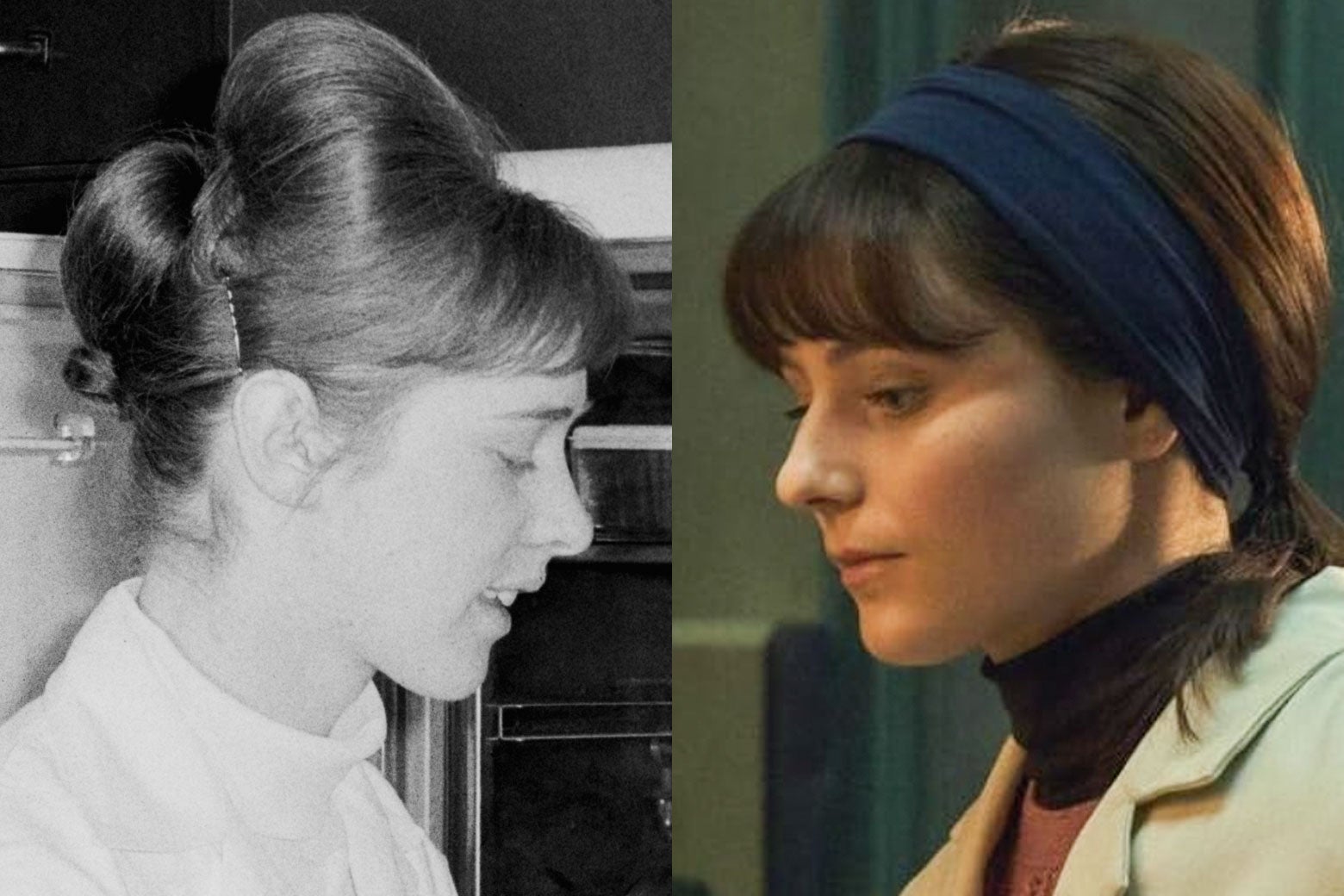

Working in a dilapidated, disused hospital wing due to lack of funds, the two are joined by former nurse Jean Purdy (Thomasin McKenzie), who becomes the central character in the film. Though she is originally hired as a lab manager, her role expands to include preparing the cultures in which the retrieved embryos are stored, recording the data from experiments, and, most importantly, looking after the interests of the 200 women who donated their eggs to the experimental work, desperate to find a cure for infertility. The team’s efforts eventually result in the birth of the world’s first “test-tube baby”—Louise Brown—in 1978, but only after 10 years that encompassed 457 attempted egg retrievals, 331 attempted fertilizations, about 221 embryos, and five pregnancies. We look at what’s fact and what’s fiction in this account of the research that has had such a massive impact on families everywhere.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Central Press/Hulton Archive/Getty Images and Netflix.

Was Jean Purdy Actually Banned From Attending Her Church?

Before joining the research team, Purdy, who lives with her devout mother, is a frequent churchgoer and committed member of her congregation. But as word spreads about the nature of the team’s experiments, Purdy is told she’s not welcome at the church unless she quits her job, and ultimately her mother says she can’t live at home anymore as long as she continues the IVF research. Purdy nevertheless refuses to quit.

Reproductive medicine historian and co-author of the definitive study of the Edwards–Steptoe IVF research Martin Johnson found that Purdy was indeed a devoted Christian, although we were unable to confirm whether she was discouraged from attending her usual church or her mother threw her out. However, it is certainly true that the IVF research attracted the ire of organized religion, especially the Catholic Church, which viewed with alarm the possible disposal of fertilized embryos that weren’t implanted (to the point where it officially protested Edwards’ receiving a Nobel Prize in 2010). The Vatican also objected to the procedure because the embryos were not the result of conjugal sex.

Was Purdy Really Sexually Liberated?

In 1969, before joining Edwards’ team in Oldham, in the north of England, Purdy is working as a technician at a lab in Cambridge, when one of the researchers, Arun, takes a shine to her. He asks her out, and despite her strict religious upbringing, at the end of the evening she says they can have sex as long as he doesn’t get attached.

This is highly unlikely to be based on actual events, and Arun is most probably a made-up character. According to Barry Bavister, a Ph.D. student of Edwards’ whose work with hamster embryos played a crucial role in Edwards and Purdy’s ability to create cultures suitable for preserving sperm and extracted human eggs, “Jeannie was a devout Christian who told me that she was ‘saving herself for marriage.’ The movie’s depiction of her intimate relationship with a fellow lab researcher ‘Arun’ is, to the best of my knowledge, pure fiction.” Moreover, Bavister was so incensed that he posted on the film’s IMDb page: “Jean Purdy was my friend and colleague; I regard her as a heroine who devoted her short life to the alleviation of infertility. So, I am especially outraged at her portrayal in the movie as a woman who ‘slept around but couldn’t get pregnant herself’ as she is shown telling her mum.”

As well, the film shows Purdy and “Arun” getting down on the dance floor in a club to some late ’60s rock, but research by Johnson and his co-author Kay Elder, who became Steptoe’s clinical assistant in 1984, revealed that Purdy’s off-duty pastimes included listening to recordings of classical music and playing the violin, hobbies that suggest she might have been more inclined to spend quiet evenings in than go out clubbing.

Was Muriel Harris a Real Person?

Having persuaded Steptoe—who has developed a new, less invasive technique for embryo implantation—to join the project, Edwards and Purdy travel four hours to Steptoe’s clinic, where they are greeted by the clinic’s no-nonsense West Indian “matron” (as senior nurses were called) Muriel Harris, who puts them to work making the lab fit for purpose. Organized and capable, she becomes a valued member of the team.

In fact, Steptoe’s operating-theater superintendent was called Muriel Harris, but she was a white British woman who was born in Cornwall. So dedicated was Harris to the research that she organized a team of “volunteer” unpaid nursing staff to help recover eggs for fertilization, a process that often required unsociable hours. It seems likely the film changed Harris’ nationality to pay tribute to the large number of West Indian nurses recruited to strengthen Britain’s National Health Service after World War II.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by PA Images via Getty Images and Netflix.

Was There an “Ovum Club”?

Purdy initially treats the women donating their eggs as a sort of superior form of lab rat, but gradually, she starts perceiving them as individuals and tries to make the experience less alienating and emotionally grueling. After learning that the volunteers have started calling themselves the “Ovum Club,” she organizes a group beach trip to raise spirits.

It’s not known if the beach trip ever happened, but the Ovum Club certainly did. Grace Macdonald, the mother of the second “test-tube baby,” a boy named Alexander, recalled her excitement at being accepted into the research program. “I made some wonderful friends,” she said. “We called ourselves the ‘ovum club’. We knew we were involved in something very special, and that taking part was about more than just us. The other women were very generous with their feelings. I remember one of the other patients saying to me ‘if it doesn’t work for us Grace, it will work for someone else.’ ”

Was Purdy Herself Infertile?

When Arun proposes, Purdy turns him down without telling him her real reason for doing so: She knows he wants children and she is unable to get pregnant due to endometriosis. Later, she has a consultation with Steptoe, who tells her that her endometriosis is severe and he can’t help her. It is this personal understanding of what infertility means that motivates Purdy to work so tirelessly to help Edwards find a cure.

It seems very likely that Purdy did suffer from the disease. Physiologist Roger Gosden, who worked under Edwards and wrote a biography of Purdy, told Time that a close friend of Purdy’s had mentioned to him that she suffered from episodes of acute pain; some were bad enough to require hospitalization, a symptom consistent with endometriosis, which, he said, “has been assumed to be the cause of a problem that she had over many years.” However, he also said he doubted whether the immensely private Purdy would be happy to see her gynecological issues being aired on the big screen: “I don’t think she would want to have been depicted as a victim of a disease.”

Even if Purdy did have endometriosis, it is unlikely that Steptoe could have diagnosed her from a pelvic exam in the mid-’70s. According to Fiona Kisby Littleton, an editor of Presenting the First Test-Tube Baby, at that point ultrasound and laparoscopy devices were not yet available, making the disease “extremely difficult to diagnose.”

Was Purdy Really Seen as an Equal Partner to the Male Scientists?

The film starts out at a ceremony to dedicate a plaque on the site of the research lab to Edwards and Steptoe, and Edwards insisting that Purdy should be on the plaque as well. Later on, when Purdy takes three months off to care for her ill mother, the project shuts down because it can’t function without her. Then, when the two doctors are photographed holding newborn baby Brown, Edwards pulls Purdy into the picture.

This is largely, and refreshingly, true. Edwards did campaign to get Purdy added to the plaque (which she was, eventually, in 2022, along with Muriel Harris), and at a lecture on the 20th anniversary of clinical IVF, he announced: “There were three original pioneers in IVF, not just two.” Far more than just a lab manager, between 1970–85 Purdy was Edwards’ co-author on 26 academic papers about IVF that appeared in leading British medical journals Nature and the Lancet. And recalling the time she took off from the project, he said, “Jean’s cooperation had become crucial. It was no longer just Patrick and me. We had become a threesome.”

Edwards’ and Steptoe’s acknowledgment of her contribution stands in contrast to another, slightly earlier mid-20th-century team working on a transformative scientific breakthrough. Watson and Crick discovered the double helix, unlocking the language of DNA—but Rosalind Franklin, a chemist and X-ray crystallographer who captured painstaking X-ray diffraction images of DNA, was crucial to that discovery. Watson (who, it’s worth noting, dismissed the IVF team’s work as “infanticide”) and Crick did not credit Franklin’s contributions, especially after she died in 1962, shortly before they won their Nobel Prize.

There is one other woman whose contribution to the IVF project was essential but who is not mentioned in Joy. Although the film suggests that work ground to a halt after the British Medical Research Council refused to finance the team, in fact the researchers were able to continue thanks to funding from an American heiress, Lillian Lincoln Howell. She donated approximately $100,000 between 1969 and 1978.

Purdy’s greatest contribution actually happened after the birth of Louise Brown, when the NHS refused to support the transplant services any longer. It was Purdy who found the site for a private clinic near Cambridge and who did the lion’s share of fundraising over the course of two years, eventually opening the world’s first IVF clinic, Bourn Hall, where she helped launch fertility services as technical director. In 2018 her contribution was recognized with the blessing of a new headstone memorializing her as “the world’s first IVF nurse and embryologist, co-founder of Bourn Hall Clinic.” Louise Brown laid flowers on behalf of the families who were beneficiaries of her work.

This post was originally published on here