Prasanta Chakravarty.

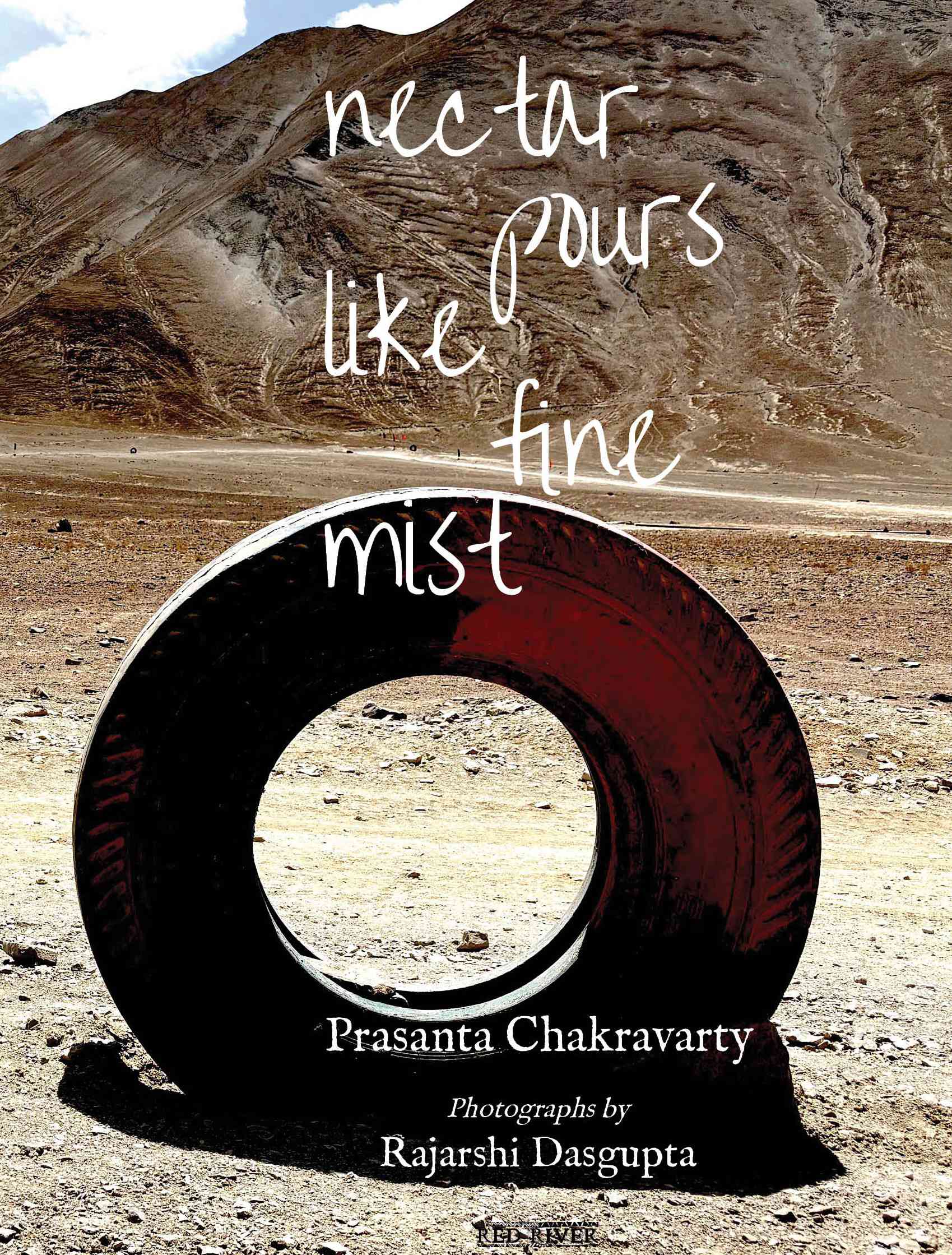

Prasanta Chakravarty has published two collections of poetry in a 12-month period – Nectar Pours Like Fine Mist and The Aravali Quatrains. The former is a collaborative work with Rajarshi Dasgupta, whose photographs are integral to the work. Chakravarty teaches English Literature at the University of Delhi and edits the web-magazine Humanities Underground. He spoke to Scroll about his books and the impulses behind them.

Two books of poetry this year. Would you like to tell us about the themes and motifs that run through the collections?

Frankly speaking, I do not believe that poems can be reduced to theme-bearing texts. It is very difficult to write about or explain utterances or ditties anyway. But the traces that unite the two miscellanies are perhaps an insistence on the miracles that the whole of creation bequeaths upon us at every radiant instant. And yet we realize the significance of letting go: welcoming change with grace and celebrating the lovingly familiar in joy and sorrow. Now that I look back, the common thread that runs through the lines collected in Nectar Pours Like Fine Mist is perhaps to do with our place and predicament under inevitable circumstances – a realisation that as thrown beings we can uncork and celebrate the life-force only by splicing open time. How does one appreciate the sublimely beautiful things around us when time seems to be pressured, careening down the cliff?

“Pulsation in the vein/Ten thousand years/ of velocity/in a globule”

This new set of poems is a kind of concentrated, felt digression to me, a detour to reach nowhere farther than the most familiar – where the marvellous hides. Is there any higher deliverance than various crossings in living itself? At every bend a surprise. In the momentary glimpse we rise and our souls turn minstrel-like. We start singing; walk directionless.

“My rucksack is obtuse/and tourism a trespass/Can you rearrange/ my legs?/I’ll walk.”

In the vastness and intricacy of creation, we form bonds. We pledge and assure each other. Such assurances are magical; and yet the contours of those moments evolve into something entirely new eventually. Duration changes gear. Most of all, our untold, heaping selves collide within the ribcage at every bend. We are and are not. All relations are beautiful and yet insistently vulnerable and contingent. Fragile and tremulous. Is it not that our surroundings are the imprints of time – like my holding of the chalk as it grates the blackboard, or feeling the traceries of the anklet on my beloved’s foot? And yet, change blurs and smudges time, bringing forth a quality that is in perpetual tension with our habits and interests. It gradually dawns upon one that time and changing matter are the real actors: playing their part, appearing from nowhere and disappearing in wonder.

And are the concerns in The Aravali Quatrains, published earlier this year, different?

The Aravali Quatrains, published in January, is the other side of the same quest, as I see it. There are 52 quatrains in the quiver. Each a kind of paper boat swimming in the flood. Their bobbings and pulses serve as heart-beats that measure their own duration. One may call each quatrain a spell of enthusiasm. Or, to put it more pointedly: each quatrain serves to mark the taut relationship between enthusiasm and a gathering tension perhaps?

All disgrace has untied me

Your abandoning has cleansed me

Whose dearest ones to the abyss gone?

Come, together, we shall make some salt.

The sense of common bankruptcy and destitution that can come from some felt and deeper attachment needs no attestation from any affiliation, party, ideology or method. Through the bushes and the briar we make our way. But those paths are also paved intricately with the filigreed work of yearning. Once all doubt is gone, this longing shimmers bright. It lurks just beneath the surface: we crave for touch, the roost, the hearth.

My lectures I have prepared well

Pupils come and wait

I slur an digress, halt and mumble

Aching for the nest

Doting quivers within a scintilla of the essential glance – of burning fingertips that touch, a morsel of rice offered by my loved one. Sentimental length of time is like a spray of flowers, a corsage drenched in adoring and treasuring intensity. And that is the reason why all illusions are beautiful, all fiction throbbingly real. Each such slice of sentimental time is a reversible journey from craving to being bereft and a renewed return to essential dwelling. Between the firmament and the ground, we hover. Poetry hovers too. Shall human creatures carry this sense of homesickness at home forever? Is there a force that makes and breaks all tenderness and devotion? In and through the sheer force of attachment, our bodies are broken into pieces, butchered and gathered in little mineshafts of loving fiction. There is no respite.

You burn and sieve all husk and grain

Calligraphic glaze

In Iron grates you peel my skin

The naked rock within.

What are the processes behind your poetry? Are there inspirations and influences? How do you organise your poems?

When I look back to the initial moments that gave birth to the first few lines of the two collections, I see an increasing hesitation in articulation. I am not being able to say things with emphasis or even communicate with others – in my songs and poetry. There is too much noise around, far too many assertions. Relentless cycles of glee and anxiety bury us.

There is a marked difference in these compilations with the poems in my earlier collections. Indeed, there has been an inward demand to utter things which lie outside of the pail of arguments, loquacity. One realises that an imaginative work cannot be a sermon in disguise. I remember WB Yeat’s inspired words: “We make out of the quarrels with others, rhetoric, but out of the quarrels with ourselves, poetry.” Giving attention to our inner selves and to our interlocutors and materials that lie strewn all around us could take us away from the bric-a-brac and arrangement of language – sometimes called poesy – to the surging chaos which we call living. For instance, each cluster of the gulmohar/krishnachura flower contains an infinite variety of particular reds, though we usually do not distinguish between them. The variations seem uniform. But if attended closely, we shall find that the obvious colour of any discrete flower is actually infinitely abstract. Observing, and then assimilating, abstraction in pulsating matter requires a kind of attentive distraction. Fragmentary utterances emerge sometimes. They arrive. We feel rhythms that light us up as we attend closely to the chaos. I can comprehend all these, but am I being able to express these in my words? Am I being smug or too distracted in my own assertions?

Anyway, in closely packed utterances there is a danger, I know. The minimal form in poetry can easily turn into little nuggets of wisdom. The obverse is also true: the form may simply turn into imagist brushstrokes or modes of marking fictive disruption where meaning is not an essential component. Neither of these approaches interests me, but I have often been drawn to the compact poetic utterances of Abbas Kiarostami, Mukund Lath, AE Houseman and Sisir Kumar Das – each of their styles, and approaches to the short lyric, are different of course. Instead of wisdom, I think the idea of the partial whole is closer to my sensibility.

Photographs are integral to Nectar Pours Like Fine Mist.

This collective work with Rajarshi Dasgupta, where each of us did our own thing – writing poetry, taking photographs – could not have come about without years of being close friends, sharing obsessive concerns and passions, and serious disagreements about art and thinking. Beyond their figurative mode, there is a sense where the photographer has always found his friend’s poetry charged with nocturnal colours and raining with mysterious gestures. I may have found my friend’s photographs curling into deeply solitary and other spaces of everyday and secret vacations. Where they meet (I feel) is in restrained and silent intervals, in conversations that break up and disperse their identities, and in collaborations where they become more vulnerable.

Excerpted with permission from Nectar Pours Like Fine Mist, Prasanta Chakravarty, photographs by Rajarshi Dasgupta, Red River.

This post was originally published on here