As Election Day unfolded, speculation swirled about what a new administration in Washington might mean for cities, metropolitan areas, and communities across the nation. Over the past four years, President Biden’s administration ushered in unprecedented federal investments in industries, infrastructure, clean energy, and more. Now, the election results offer a clearer sense of the future for the place-based, locally led solutions that state and local leaders have championed in recent years.

Ample evidence suggests that the incoming Trump administration, backed by a compliant legislature, will prioritize tax cuts and deregulation. The president-elect has also signaled opposition to social safety net programs, diversity initiatives, climate policies, and immigration reforms. Yet the potential impacts on critical areas such as artificial intelligence, workforce development, and infrastructure remain uncertain.

To explore these issues, this compendium brings together insights from Brookings Metro scholars, examining how the next four years might shape cities, regions, and communities across the United States and the related impacts on people, economy, and environment. It leads off with a look at the nation’s evolving demographic trends, which will profoundly influence places regardless of who occupies the White House.

One thing is certain: state and local leaders, across both public and private sectors, will face a dramatically different federal landscape starting in January. At Brookings Metro, our mission is to partner with these leaders to ensure that our research and expertise inform practical, scalable policy solutions. In this time of uncertainty and heightened federal challenges, it is more important than ever that we do so.

William H. Frey

Trump’s policies need to recognize the nation’s underlying demographic shifts

In light of President-elect Trump’s sensational campaign characterizations of open borders, illegal immigrants, and negative stereotypes about immigrants’ country of origin, race, or ethnicity, his new administration is certain to begin implementing an array of policies such as the deportation of immigrants and abolishment of diversity initiatives in early 2025. While such actions might be popular with his heavily white and older voter base, they disregard fundamental shifts in the nation’s demographic structure that both increased immigration and elevated attention to diversity—especially younger minorities—that is crucial for the nation’s future economic vibrancy.

U.S. population growth is slowing and aging rapidly. The 2010–2020 decade showed the second-lowest growth in the nation’s history along with rapid aging. In that decade, the baby boom-infused population ages 65 and older grew by nearly two fifths, while the labor force-aged population grew less than 5% and the population of those under the age of 18 actually declined. In a future of decreasing births and increasing deaths across an already aging population, moderate to high immigration levels are vital for long term national growth, and countering what would otherwise be extreme aging. (See Figure 1.)

Census projections based on a range of immigration levels make this clear. Under current (or moderate) immigration levels, the U.S. population would start declining after the year 2080. Under low immigration (similar to those in Trump’s first term), declines would begin in 2044. And under zero immigration, the U.S. population would decline next year. Only under an assumed 1.5 million immigrants per year arriving in the country over the next 75 years—a level observed occasionally in the past—would the U.S. population continue to grow over time.

Immigration is not just necessary for population growth but also for making the population younger, as immigrants and their children are more youthful than the native born. Under the same alternative projections above, low or zero immigration would lead to zero or negative population growth in the nation’s labor force-age population by 2035. This is crucial especially because it is the labor force population that is largely responsible for funding the Social Security and Medicare programs that serve a good part of Trump’s base and is widely supported across the political spectrum. Thus a sharp decline in immigration would put at risk those and other state and local funds, contributed by working aged taxpayers.

Of course, immigration is also responsible for the growth or decline in many states and communities In 2023, immigration was responsible for all of the population gains in 13 U.S. states and 11 large metropolitan areas. An analysis by my colleague, Alan Berube, shows that immigrant populations accounted for 31% of 2000–2020 growth in big cities and a good part of the growth of smaller metropolitan and nonmetropolitan counties. Thus policies focusing on the integration of immigrants are necessary in all parts of the country.

Rather than casting immigrants as “un-American” and engaging in a plethora of programs designed to demonize those already here, it is crucial to move the discussion to a serious analysis of the importance of immigration for the nation’s demographic and economic growth, and how broad policies such as comprehensive immigration reform can address future needs both nationally and locally.

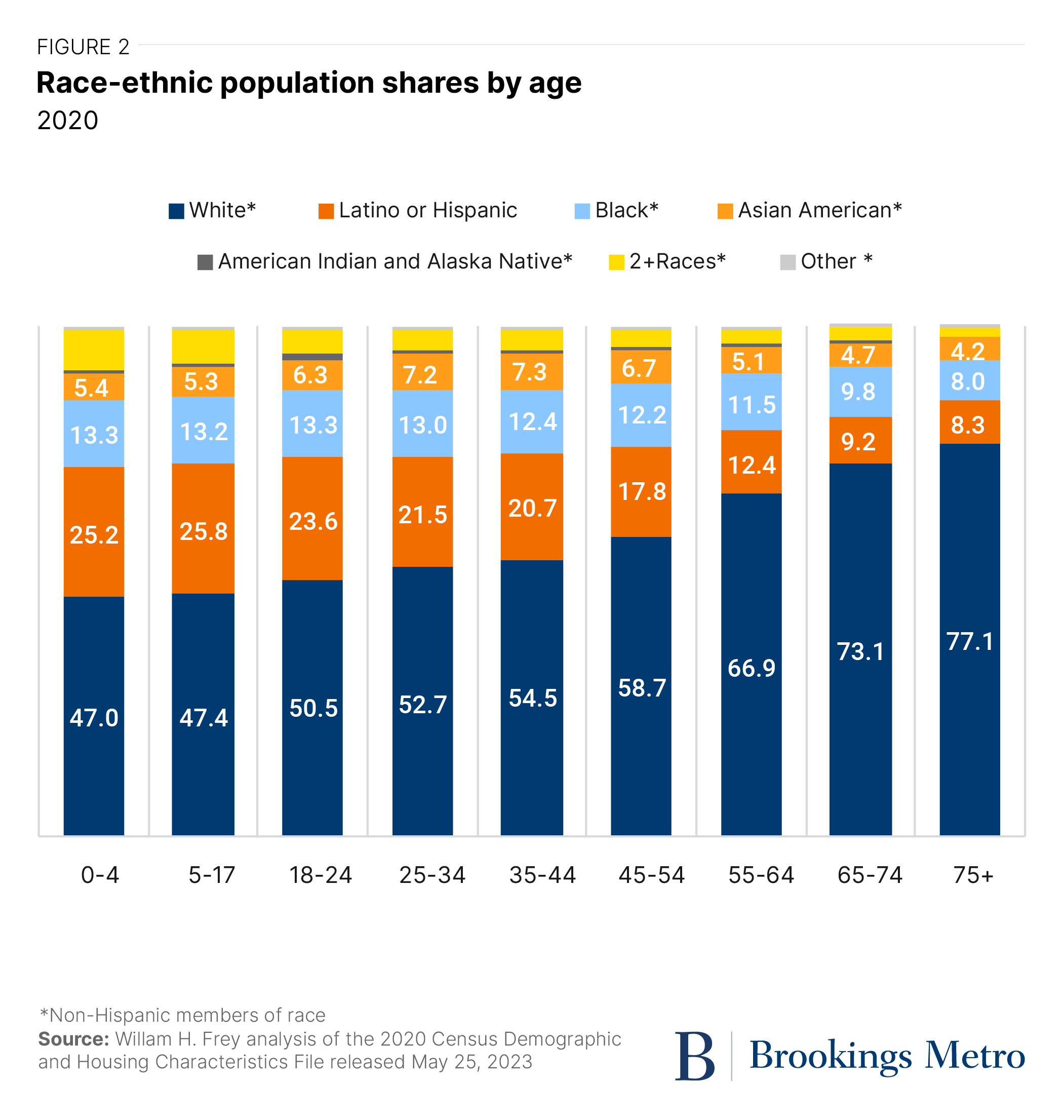

Another seismic demographic shift that is relevant to the nation’s future is the rise of its racial and ethnic minority populations. The 2020 U.S. Census showed decline in the country’s aging white population over the previous decade such that minorities accounted for all of its population growth and now comprise more than 40% of the national total. Yet aging is not race neutral. As the white population ages out of younger age groups, racial and ethnic minorities, including Latinos or Hispanics, Asian Americans, and persons identified as two or more races, have been filling the gaps, especially among the younger population, (See Figure 2.)

The majority share of the U.S. population under the age of 18 is now “minority white,” with Latino or Hispanic and Black populations comprising nearly two fifths of children nationwide. In all states, the child population is more racially diverse than older populations, and in most, this also applies to the younger working aged population. This is especially the case in Texas, the state with the biggest-gaining child population, where minorities comprise 70% of children.

Sharp racial disparities in child poverty and other socioeconomic measures continue. They represent the “starting point” of a trajectory of racial and ethnic inequalities that have been evident among young adults in recent generations with respect to educational attainment, homeownership, wealth accumulation, and other measures. They also reflect the current family context of these young people with respect to receiving adequate nutrition, health care, and social services.

The U.S. is at the cusp of significant age and generational change. Its child population, growing at historically low levels, will be feeding into a modestly growing labor force that will need to support the Social Security and Medicare needs of a rapidly growing senior population as well as the nation’s ongoing productivity. The major engine of this modest growth of the young is a new generation of children born into families of color—the largest groups of whom stand on the wrong side of rising racial and ethnic inequalities.

Although “demography is destiny” is often dismissed as an overly simplistic view of the future, it is an apt one for examining the issues addressed here. This is not the time to make bad choices on federal immigration actions as we face a rising senior population and slow-growing labor force. It also is not the time to put the brakes on programs that address the diversity disparities among America’s youth—the future of our labor force. While some of these programs exist at the state and local levels, the federal government as directed by the new administration will set the tone. It is imperative that those that shape its tone come to recognize the importance of such policies for the decades ahead.

Xavier Briggs

It’s time to reinvent the pursuit of equal opportunity through government and markets

A rancorous political campaign and the second election of Donald Trump as president have major implications for the pursuit of “opportunity for all,” one of America’s most treasured, if contested, ideals.

On one hand, there’s the polarization factor. Trump and his allies have stirred tremendous anger about “diversity, equity and inclusion” strategies he claimed are part of a dangerous woke agenda by the radical Left. This kind of argument has long been a staple in American politics, typically via appeals to economic resentment, racial and cultural grievances, and zero-sum thinking, as in ‘doing more for your group surely means less for mine.’

In decades past, transitions to a Republican president have led to substantial cuts in federal funding for civil rights enforcement and aid programs that help low-income people of all backgrounds—but also to tabling any ambitions to effectively use government contracting, say, and other tools to expand business opportunities and wealth, especially for racial minorities and sometimes for women, veterans, and other groups facing barriers too.

Based on the president’s “Day One” agenda, budget framework, and first State of the Union address, the American public will begin to learn whether that template holds and, if so, whether congressional Republicans are inclined to refuse some major funding cuts proposed by the president, as they did in Trump’s first term in office. The launch of a nongovernmental, commission-like Department of Government Efficiency is not encouraging on that score.

On the other hand, by a wide and steady margin, voters—not just conservative judges or Trump’s cabinet picks—have been rejecting affirmative action policies for years now. This is true even in demographically diverse, liberal strongholds such as California, where, in 2022, voters, for the second time in a generation, said no to a ballot measure that would allow for, among other things, race-conscious college admissions and preferences in government hiring and contracting.

Public opinion research consistently shows that Americans know discrimination is illegal and also agree—across lines of race, educational attainment, party affiliation, and other differences—that it is wrong. But research also shows that white Americans significantly overestimate how much measurable racial progress has actually taken place.

The pivotal question, then, is two-pronged. On the first prong is the table stakes: Will we make meaningful effort to enforce rules barring discrimination on the basis of race, gender, and other traits? Funding levels matter, but public and media attention tends to matter even more, so tracking perception versus reality will be key on this issue, like so many others.

The second prong (setting aside left and right mantras and polarized DEI labels) is what additional steps, beyond detecting and deterring illegal discrimination, are warranted in America, to move us toward genuinely broad-based opportunity? Long experience and recent politics suggest several steps, which could garner substantial and durable public support, and significant state, local and private sector commitment, whether or not they are championed by the next president.

One is betting big on community colleges, which serve diverse, high-need groups of students, including working adults trying to shift into higher-wage occupations and nationally important “strategic sectors,” and also—as my colleague, Andre Perry, has underscored, historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs), which have long produced most of the nation’s Black doctors, engineers, and other well-paid professionals. Another is using the bipartisan drive to onshore manufacturing, and embrace new power sources and a more resilient energy future, to dramatically expand diverse-owned supplier businesses—not just manage relatively small, compliance-oriented set-aside contracting programs anchored in a 1970s politics long gone—as our collaborative research on America’s next “industrial revolutions” is making clear.

A third is respecting the role of unions. They are now enjoying more public support across the political spectrum than at any point since the 1960s, while also encouraging alternative forms of worker voice in non-unionized workplaces, as investments in manufacturing, generative AI and other disruptions affect the job market and quality of work.

Finally, state and local government momentum around the equitable delivery of government is significant, and it shows no signs of turning back as voters nationwide broadly voice distrust in institutions and demand change. As Brookings research has shown—contrary to the inaccurate claim that President Biden’s Executive Order on promoting equity codified favoritism—voters understand that one-size-fits-all government does not serve any group or place, whether small rural town or big metropolitan area, very well.

Voters value tailored, more responsive approaches, if they are crafted transparently and fairly. Policymakers and implementers at all levels of government know how to do much better, and the urgent need to act on that know-how might be the most vital common ground of all.

Manann Donoghoe

For climate action, there’s an opportunity to redouble efforts at the local level.

The 2024 election was not a referendum on climate action. In fact, despite two major climate-related disasters occurring within 2 weeks of in-person voting, climate hardly featured in the election campaigns. Yet, president elect Trump’s openness as a climate sceptic, and his actions in his first term in office, make his disdain for climate policy clear. In a crucial period for action, these next 4 years are consequential to the effectiveness of international emissions reduction efforts needed to keep global warming as close to 1.5 degrees Celsius as possible.

And yet it’s difficult to label the new administration, and many members of the incoming 119th Congress, as anything other than anti-climate action. So, is there any room for progress federally? There may well be in at least two areas.

First, one effective element of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was to demonstrate the power of climate action as industrial policy. The IRA was popular among both homeowners and businesses, with unanticipated uptake of tax rebates for homeowners to upgrade household energy efficiency that have helped spur demand for businesses to scale up renewable technologies. While Trump has indicated a desire to unleash new oil and gas extraction and cut these tax breaks, the general public and the private sector have seen the benefits of this policy. They may pressure the administration and Congress not to hobble the now growing market for renewables.

Second, before the climate justice movement and the rise of public policy for resilience and adaptation, climate policy was disaster policy. To no small extent in the United States, it still is. Disaster policy was one of the few climate issues that saw bipartisan legislation passed in 2023, including substantial reforms to Federal Emergency Management Agency that increased the coverage and effectiveness of disaster payments for households. Disaster policy could provide a vehicle to continue passing needed climate reforms, including shoring up insurance markets, improving climate risk disclosure, and increasing disaster relief.

Finally, while the results of the 2024 election feel like a climate setback, this moment is also an opportunity for local policy experimentation. The gaps created by federal inaction will only increase the demand for local tools, policies, and structures for action. For all its depiction as a global issue, disconnected from the lives of working-class people, the impacts of climate change are felt most locally. They amplify “bread and butter” issues such as inflation and household costs, increasing electricity prices and insurance premiums, and they cause administrative headaches for elected officials, including infrastructural failure and civilian displacement. Irrespective of political ideology, climate impacts, from heat waves and sea level rise to droughts and hurricanes, will continue to cause tremendous economic damages and personal suffering.

Indeed, across the U.S. where voters had the opportunity to show their support for climate policies through ballot measures, they voted to conserve the environment and take action on climate justice. Local leaders who want to stay in office will be searching for the tools and policies they need to climate-proof their infrastructure, minimize private property losses, and protect vulnerable communities. In this way, local government policy experimentation could provide scalable frameworks for when the federal window again opens for climate policy reform.

Annelies Goger

It’s time to stop using deficit language for work-based learning

Whether one had attained a college degree was a significant factor in voting behavior in the 2024 election. This may not come as a surprise given the debates about elitism in higher education, the growing bipartisan support for skills-based hiring, and concerns about rising inflation. In short, many Americans feel left behind in the U.S. economy today. Despite low unemployment and tight labor markets, many people without a college degree feel their skills, knowledge, and experience are unjustly devalued in the labor market.

Educational attainment is now the identity politics of our time. The evidence is clear that the institutions we have inherited for higher education, career and technical education, and hands-on training in the workplace are seriously inadequate to meet the needs of today’s rapidly changing digital economy. The inability of legislators, K-12, higher education, and workforce leaders to adjust and adapt these institutions has had serious consequences by eroding public support and trust in our educational institutions.

One place to start repairing that support and trust is to honor and reclaim the value of learning-by-doing and stop using the terms “non-credit” and “non-degree” to describe it. This deficit-based language used to describe any kind of learning that takes place outside a formal, accredited program—typically referred to as “non-credit” and “non-degree” programs or credentials—itself contributes to the continued devaluation and second-class status of the individuals who hold them in the labor market. Until our society makes the cultural shift away from such deficit language, it will be impossible to build the case that employers and learners should value it more.

I am not arguing that all learning should be formalized, or that we should sweep away all the programs themselves. Because “non-degree” and “non-credit” refer to more than just work-based learning, it is important to think through a full typology of what this learning is and how it adds value for a learner or employer. Creating more differentiation across different types and forms of learning and finding ways to recognize high quality hands-on learning pathways for credit in the formal system will give individuals with work-based learning credentials and degrees more status in the labor market and employers a better sense of what skills and experience that individual has. The lack of consistency, clarity on progressions, and choices makes it hard for learners and employers to understand what these credentials mean or to determine quality.

There is a lot of existing innovation to build on to move this conversation forward. Many states have already started to have sophisticated conversations about how to value non-degree credentials or “credentials of value.” Researchers and practitioners also have mapped out how to define quality among non-degree credentials. There is a robust network of academics and researchers working on non-degree credentials and an organization that provides a registry and coding language for navigating the chaotic jungle of credentials. But all of this important work seems to be undermining itself and our human capital by keeping to the deficit language of “non-degree” and “non-credit.”

Ultimately, without ditching this deficit language, and by extension the individuals who have earned these credentials and have valuable work experience and skills, then this primary descriptor will continue to communicate a sense of alienation among Americans who have not completed a college degree, which is a majority of Americans. So let’s figure out how to value learning in all its forms, and then value the many talented Americans who learn more by doing than one could achieve in an accredited classroom alone. Stop using “non-credit” and “non-degree.” Use affirmative descriptors to give value to these skills, knowledge, and experiences.

Joseph W. Kane

Accelerating infrastructure projects and jobs will not stop anytime soon

Washington’s rapid political shift is fueling speculation on many fronts, but federal, state, and local leaders will continue to drive historic infrastructure investments over the next couple years (at the very least), including the support of millions of jobs nationally. The $864 billion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) has a five-year runway, and the country still has two more years of implementation to go—from rebuilding roads, to fixing water pipes, to installing new broadband systems. Bigger questions surround the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), particularly around climate-focused tax incentives for electric vehicles and other technologies, but even these investments have already unlocked new collaborations and efforts around infrastructure workforce development.

The challenge facing state and local leaders, especially, is the extent to which they can take advantage of the remaining IIJA funding to catalyze both short- and long-term infrastructure workforce development—and not just focus on immediate construction projects and jobs. Many of the transportation departments, water utilities, and other infrastructure employers receiving funding continue to follow business-as-usual training, hiring, and project development practices, which can limit the ultimate impact of this funding, particularly to support more durable work-based learning opportunities, sector partnerships, and more. These employers, alongside other workforce leaders, face a pressing need to coordinate and test new approaches with the funding that remains, amid a growing wave of retirements and other recruitment and retention needs.

The first Trump administration signaled interest in both infrastructure investment and jobs, but did not get legislation across the finish line or always provide clear supports (via federal agencies, such as the U.S. Departments of Transportation and Labor) to help state and local leaders address their infrastructure workforce needs. The uncertainties surrounding new leadership at these and other agencies and their priorities also cloud what the next few years will look like. State and local leaders consequently have all the more reason and urgency to tackle their workforce needs head-on, by maximizing the window of federal infrastructure funding that remains and positioning themselves for what comes afterward.

Farah Khan

Prioritizing wealth at the expense of equity and inclusion at the federal level will require urgent local action to protect marginalized communities

President-elect Trump’s proposed cuts to social safety net programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Medicaid, and housing assistance, combined with extending the 2017 tax cuts that disproportionately benefited the wealthy alongside lifting the cap on state and local tax deductions, underscore a broader agenda prioritizing the interests of the rich while marginalizing vulnerable populations. Framed as fiscal prudence, these reductions are intended to offset the costs of extending tax breaks for the rich, yet they will disproportionately harm low-income households.

When paired with Trump’s broader efforts to dismantle diversity programs and censor discussions of race and gender in education, these policies are especially harmful. Marginalized communities, including Black, Latino, and immigrant populations, face a dual threat—reduced access to economic safety nets and systemic attempts to erode racial and gender equity—as rhetoric targeting diversity initiatives finds solid footing in policy.

What’s more, these proposed federal policies will exacerbate systemic inequities, underscoring the critical role of welfare economics at the state and local level in analyzing and advocating for equitable resource allocations and the inclusion of underrepresented communities in these policy arenas. In this context, state and local governments have a unique opportunity to adopt economic policies that prioritize inclusion and address the compounded harm inflicted by regressive economic and social policies. This will require a deliberate focus on bridging divides, fostering resilience in underserved populations, and advancing productivity through equity-driven initiatives.

Molly Kinder

Workers will face more disruption from generative AI. How federal and state policymakers police it will be key to workers’ wel-being and the broader economy.

The potential impact of generative Artificial Intelligence on work and workers is likely to be a key policy issue in 2025. In many ways, the recent presidential election litigated past economic disruptions, especially to blue collar work, with President Trump proposing to crack down on trade and illegal immigration. Surprisingly, neither presidential candidate addressed a key current and future source of disruption to jobs: generative AI.

Yet as Mark Muro, Xavier Briggs and I recently wrote, this silence belies a stark reality: the Trump administration will inherit an economy already changed by this new and disruptive technology—and heading for much greater disruption in the next few years. Even some of President Trump’s closest advisors, including Elon Musk, have warned of AI’s threat to jobs.

The new Trump administration and the incoming 119th Congress are uniquely positioned to shape the country’s response to this fast-moving technology, including its impact on millions of American workers. President-elect Trump has pledged to repeal the Biden White House’s AI Executive Order and signaled his opposition to regulating AI. But it is critical that Washington balances its support for AI innovation with proactive policies, regulations, and safeguards to ensure that American workers share in the gains from this technology, avoid its harms, and shape its trajectory.

While the outlook for pro-worker AI regulations is uncertain at the federal level, states will continue to play a key role in pioneering new legislative approaches to shaping AI’s impact on work. A growing number of states introduced legislation this year that would regulate AI’s use in the workplace, including protecting workers from automation and job losses. Expect to see more policy innovations in 2025, with more state legislatures drafting bills to introduce safeguards for workers.

Tracy Hadden Loh

How is Trump’s reelection likely to affect US cities and regions?

The election of a “red trifecta” to federal leadership might at first seem oppositional to largely blue American cities and regions. Certainly, local governments had a friend in the Biden administration, which extended game-changing generational aid through the 2021 American Rescue Plan. Yet it is not clear whether either the new Trump administration or incoming 119th Congress will actually follow through on all of the various priorities that were emphasized during the election campaign, some of which (such as mass deportation) could certainly have concentrated impacts on specific places (not all of them urban).

If local governments across the country simply find themselves on their own, then this is not that different from the historic status quo in which for much of American history local governments have had their own revenue sources, domains of responsibility, and varying capacities to match. If anything, at many notable periods, federal policies and “cataclysmic money” (as dubbed by Jane Jacobs have weakened American places in ways we can still see today—think ever-expanding highways, bypassed historic towns, and urban renewal projects where demolition was not always followed by quality construction.

Yet there is no clear reason to assume the second Trump administration will be just like the first. Thus, while Elaine Chao’s U.S. Department of Transportation in Trump’s first term did not advance the deployment of transportation infrastructure financing to increase the productivity of highly accessible real estate, the next Transportation Secretary may still decide that it is a good idea to empower locals to put their own assets to work.

Two legislative priorities of Trump seem very likely to advance in the early days of 2025: tax cuts and deregulation. On that first front, the Opportunity Zone program that was part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act is worth revisiting to strengthen the program’s geographic targeting, transparency, and mechanism of impact. For the latter, I anticipate a mixed bag for places. Environmental regulations that protect clean air and water saved American cities in the 1970s, and now that manufacturing has shifted to more rural areas it would be a loss to all Americans to see the natural assets of those places degraded or destroyed. At the same time, outdated securities regulations have restricted the growth of promising new forms of community capital while dubious value propositions such as cryptocurrencies have flourished.

Regulatory reform to democratize securities instruments currently only accessible to “accredited investors” could enable local places to do what they want to do without waiting for the federal government to show up: invest in themselves.

Hanna Love

A harder path forward on public safety is not a reason to lose hope

The 2024 election made two mandates clear: Voters crave strong action on the economy and crime. While crime is down considerably from pandemic-era peaks, Americans’ perceptions have not caught up to these trendlines, leaving room for President-elect Trump to champion a ‘tough-on-crime’ agenda that emphasizes punishment, deportation, and federal oversight over local criminal justice reforms. This punitive turn is a stark departure from the Biden Administration’s public health approach to reducing violence, which established the first White House Office of Gun Violence Prevention, unlocked unprecedented federal funds for localities to invest in community-led violence prevention, and supported the first gun violence prevention legislation to become law in decades, the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act of 2022.

A second Trump administration has the potential to disrupt this progress if his campaign promises are kept. It could hamstring the U.S. Department of Justice, shut avenues for police oversight and accountability, and leverage executive orders and judicial appointments to advance tough-on-crime priorities. These proposed actions also run the risk of increasing mass incarceration and fueling the racial injustice it perpetuates.

Luckily, however, the real opportunity for advancing evidence-based public safety policies lies at the state and local level. The nation’s approximate 18,000 law enforcement agencies are governed primarily by state and local law and 88% of the nation’s incarcerated population is under state control. States can enact their own legislative reforms and investigations into police accountability, and importantly, many of the preventative investments needed to improve public safety are under the purview of local governments. In Detroit, for example, after local leaders adopted a holistic, public health approach to violence reduction that doubles down on violence intervention and upstream investments in communities, they achieved their lowest homicide rate in 57 years. Similar successes have been seen in cities nationwide.

The 2024 election revealed that Americans are concerned about crime, but they are far from embracing a wholesale rejection of criminal justice reform. Across the nation in places including Travis County, Texas, Albany County, New York, Lake County, Illinois, and Orlando, Florida, voters elected more progressive prosecutors against “tough-on-crime” challengers. And even in states that voted for Trump, such as Kentucky, Montana, and Michigan, voters elected liberal judges to their state Supreme Courts.

While the federal opportunities for advancing humane, evidence-based public safety policies will likely be made more complicated by the new administration, all hope is not lost. There is a strong opportunity for states and localities to lead and strategically partner to prioritize investments in public safety that not only reduce crime, but also foster more equitable, resilient, and prosperous cities and regions. By embracing evidence and innovation, states and localities can deliver the results that voters are craving—safe, opportunity-rich communities.

Robert Maxim

The Trump administration poses risks for underrepresented workers and Native communities. Congress, states, and cities will need to step up to protect them.

Donald Trump spent much of his campaign attacking ideas that he pejoratively deemed as “woke.” This included promises to further roll back race-conscious policy in U.S. life, and to reject efforts to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion in areas such as education and employment. Yet as our new research shows, certain groups, including women, as well as Black, Latino or Hispanic, and Indigenous workers, remain significantly underrepresented in the best-paying, most digitally oriented occupations in our economy. Given that, what is needed now is not a retreat from policies aimed to connect underrepresented workers to these occupations, but rather new investments to support equal opportunity for more workers of all backgrounds.

Meanwhile, over the past four years, the federal government has made a deliberate effort to broaden access for tribes and Native American communities in federal funding opportunities, which has resulted in a record level of federal investment flowing to Indian Country. These efforts to better include Indigenous communities in U.S. policymaking culminated in October, when President Biden issued a historic apology for the U.S. government’s destructive system of federal Indian boarding schools, in which the U.S. government kidnapped Native children from their homes, cut off their ties to their families and cultures, and abused them—sometimes to the point of death. Earlier this year, the U.S. Department of the Interior recommended a set of policy actions the federal government can take to begin rectifying the legacy of the boarding schools. With Trump now set to take office, it’s not clear whether these critical follow-on steps will happen.

In both cases, Congress will need to act to support these communities if the new Trump administration refuses to do so. Growing the number of underrepresented workers in the digital economy will require new investments in digital skills development and digital infrastructure, increased access to capital, and more robust place-based investments into underrepresented communities. And Congress remains the most essential actor for investing in tribal communities because of its so-called “plenary power” over Native nations.

In the absence of congressional action, states, regions, and cities will need to do more to support these communities. State and local actors can promote more equitable access to digital work by enacting their own policies to promote digital skills, build digital infrastructure, and increase investment in left-behind communities. For Native American communities, states including Montana and Minnesota, have enacted Indigenous Education for All acts, which ensure that all students understand Native American history. Other states, among them California, have created state Truth & Healing Councils to reckon with their own legacy of harm to Native American people, and explore policy actions they can take to support and invest in Tribes and Native American communities today.

While the federal government has historically led on both of these issues, in the coming years state and local actors may instead need to enact robust new investments, with the goal of maintaining momentum and serving as a template for future federal action.

Mark Muro

Going back to state and local policymaking to sustain place-based technology development and renewal

Arguably one of the deepest revelations of the 12-year Trump era has been the national, regional, and intellectual recognition of the country’s deep divides: social and cultural, yes, but also economic and geographic. Trump’s second term is only going to sharpen those concerns, albeit while shifting aspects of the policy scrimmage.

What my colleague Joe Parilla and I call “place-based industrial policy” won’t go way, for example, but the focus will shift from “Bidenism’s” big federal challenge grants to an urgent “sustainability challenge” for past winners alongside more self-help in communities. Federal programs won’t in most cases be repealed or otherwise erased but they may be neglected, meaning that regions that have received federal launch grants now will need to channel their elevated aspirations into urgent “bottom up” efforts to shape and finance transformative develop initiatives. Some implementors will feel they are “going back” to an earlier time of less support, but at the same time many executors have learned a lot since then.

Many of them will innovate and flourish. What’s more, continued economic vitality and improved state budgets may allow for new places to emulate Biden-area winners’ strategies with their own new ventures. Brookings Metro will “stay with the story” to see what the next stage of “place-based” development looks like.

Turning to the next technology stage, it appears clear that Trump 2.0—with its ties to tech disrupters and its focus on the China competition—will place artificial intelligence (AI) at the center of its activities. This will likely entail an acceleration of AI research and development, yet speculation on Capitol Hill persistently suggests that there could a fusion here of federal AI investment with a new surfacing of place-based, region-oriented research and adoption efforts.

On this front, GOP suspicion of Big Tech could play a role in some decentralization of AI investment; so could the home-region priorities of red-state senators. In any event, a degree of attention to the geography of AI innovation and adoption would be welcome given the extremely narrow map of leading-edge AI work currently. Metro has already begun to explore the regional geography of AI talent, innovation, and adoption. Even though there is much uncertainty surrounding the deployment of AI across our economy and society, there are also many compelling opportunities for places that Brookings Metro can and will help them explore.

Stay tuned.

Joseph Parilla

Navigating uncertainty and sustaining momentum for place-based economic development in a new political era

One priority receiving bipartisan support over the past four years has been the need to channel greater investment in technology, innovation, workforce development, and industrial competitiveness to places left behind by prior waves of economic growth. As the new Trump administration and the incoming 119th Congress take office in January, the next two years will be a different environment for place-based policy.

Rather than a public investment agenda in key strategic sectors, the incoming administration will likely emphasize trade policy as the main lever for reindustrialization. As for major pieces of legislation, the bipartisan foundation of the CHIPS and Science Act offers some protection against outright repeal. It would be an odd use of political capital for Republicans to try to pull back incentives already provided to global semiconductor companies.

Yet, there is not currently widespread appetite in Congress to fully appropriate the Science portion of the legislation, including key programs such as the National Science Foundation’s Regional Innovation Engines program and Economic Development Administration’s Regional Technology Hubs program. For all the money that has gone out the door for these and other programs, further challenges such as staffing turnover in key agencies, permitting delays, geopolitical uncertainty, and an insufficient focus on building local capacity could undercut the ultimate economic benefit of these investments for an inclusive swath of workers and communities.

Yet, even if another dollar is not allocated by Congress and the new Trump administration, the $40 billion investment from place-based industrial programs—and the hundreds of billions in incentivized private investment in strategic sectors—can still offer new economic development pathways in dozens of cities, metropolitan areas, and rural communities across the country. Seizing this opportunity will require America’s complex multi-level system to marshal the capacity to implement this economic development agenda such that it actually delivers economically for American workers and communities.

As the new administration transitions in, it is crucial for implementers, investors, and policymakers to sustain the momentum. Continued partnerships across government, industry, and philanthropy, rooted in place, will be essential to maximize the economic, social, and technological impact of these potentially transformative policies. Over the next six months, Brookings Metro will be exploring the continued implementation of these place-based federal investments, distilling how emergent economic development models are structured, financed, and governed. This applied research agenda can not only improve the implementation of $40 billion in federal funding, but also surface the knowledge, networks, and ideas required to design, finance, and implement future generations of place-based economic policy.

Andre Perry

Will the Share of Black Business Continue to Grow in the Face of a Backlash?

In 2021, the number of Black-owned employer businesses (businesses with more than one employee) increased by 14.3% from the prior year. In fact, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Annual Business Survey, the number of Black-owned employer businesses grew consecutively from 2017 to 2021. Black-owned employer businesses also had the highest percentage increases in employees (7%), revenue (30%), and payroll (27%) in 2021 compared to white, Asian American, Latino or Hispanic, and Native American employer businesses.

Still, the share of Black employers, at 2.7%, is the least among other racial groups. Comparatively, white Americans owned 82% of employer businesses and made up 72.5% of the population, while Asian Americans owned 10.9% of employer business and made up 6.3% of the population. Latino or Hispanic and Native Americans1 also had disproportionately low shares, representing 6.9% and 0.8% of employer business owners yet 19.1% and 2.6% of the population, respectively.

In the face of this growth in Black-owned businesses, there has been a backlash against federal agencies that may have contributed to an increase in Black employers. In March, a federal court in Texas decided that the agency in the case cannot factor in race or ethnicity when providing support to businesses, as it breaches the Equal Protection Clause. In a different case in September 2023, a Tennessee court ruled in Ultima Services Corp. v. U.S. Department of Agriculture that the Small Business Administration’s 8(a) program discriminated against white people, referencing recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions on affirmative action. Around 4,800 small businesses that are socially and economically disadvantaged benefit from the 8(a) program through training and technical support, aiding in reducing the gap for Black-owned firms by assisting businesses that have been operational for over two years.

Brookings Metro’s Center for Community Uplift has monitored the growth of employer firms across race and place. If the recent presidential election serves as a mandate for an economy that works for everyone—and the business community plays a vital role in achieving this goal—then monitoring outcomes across diverse districts, both blue and red, and engaging with communities of varying racial backgrounds is essential for the business sector to drive significant growth and enhance overall productivity.

Martha Ross

State and local leaders will face hard decisions and difficult times should mass deportations proceed on the scale promised by the new Trump administration

The immigration priorities of President-elect Trump present state and local leaders with profound uncertainty and potentially massive disruptions. As a candidate, Trump said his administration would carry out “the largest domestic deportation operation in American history,” and upon his victory, the details are coming into better focus. Deportation on the scale Trump and his team envision would be extremely destabilizing socially and economically, as well as complicated to carry out.

Some state legislators and governors are enthusiastically supportive—and in many cases have demanded stronger immigration enforcement for years. These governors can activate the National Guard to assist with non-enforcement deportation activities and a number of states already have laws requiring state and local law enforcement agencies to cooperate with federal immigration officials. Other state and local leaders are vehemently opposed. A number of governors, attorneys general, mayors, and legislators have announced they will not cooperate and are strategizing about how to react to mass deportation efforts.

State and local leaders face a range of scenarios and for those who are opposed, the uncomfortable truth is that it will be difficult to prepare. This is partly due to uncertainties about how the new Trump administration will proceed, partly due to the disorientation that accompanies such a shift in how the United States treats immigrants, and ultimately because state and local governments do not have enforcement power over who enters and exits the country.

Trump’s initial staff appointments of Stephen Miller and Tom Homan suggest that his campaign statements were not rhetorical. In a post-election interview on Fox News, Miller said that one of Trump’s first acts would be to “sign executive orders sealing the border shut, beginning the largest deportation operation in American history.” Homan, the incoming “border czar,” stated that his Day One immigration actions would cause “shock and awe.”

There are an estimated 11 million unauthorized immigrants in the United States as of 2022, and the majority have been in the United States a decade or more. They live in about 6 million households, most of which include a mix of people who are and aren’t authorized to reside in the country. An estimated 8.3 million unauthorized immigrants are in the U.S. workforce (almost 5% of the workforce) and are concentrated in a few industries, among them agriculture, construction, and hospitality.

Homan said that the administration would prioritize certain groups for deportation—people who pose public safety and national security threats, such as people involved in drug cartels—but would also seek to remove migrants without criminal backgrounds who are in the country illegally, including by carrying out worksite arrests. As a practical matter, however, it can be difficult to find people who pose public safety and national security threats. Per ICE’s 2023 annual report, the agency removed about 5,900 known or suspected gang members in 2018 and about 4,300 in 2023. Of course, there are undoubtedly more dangerous individuals, but if the number is doubled, tripled or even multiplied by ten, it is far short of the number of people Trump would like to deport.

Since targeting “the bad guys” won’t produce the numbers the administration wants, it will have to reach more broadly into communities and the general population. Per public statements, the incoming administration is planning to deport millions of people; as a candidate, Vice-President-elect J.D. Vance suggested starting with one million. To reach this number, the administration will have to include people without criminal backgrounds. Worksite arrests are planned, and although Homan has said there would not be a “mass sweep of neighborhoods” it is hard to take him seriously.

This would be a mammoth undertaking, straining their current capacity. In 2023, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) deported (or “removed”) 143,000 people. In the previous Trump administration, ICE removed higher numbers of people—256,000 in 2018 and 267,000 in 2019—but still a fraction of what they are proposing now. Both Miller and Homan have already noted they’ll need more resources to carry out their plans. Homan called for Congress to provide funding for “a massive amount of detention beds.”

To help with the effort, Trump is planning to declare a national emergency and mobilize military assets. Per Homan, service members would be used for “non-enforcement duties” such as transportation; he mentioned turning to the U.S. Department of Defense for assistance with flights to supplement ICE’s resources. Trump also has indicated he would turn to the National Guard, which would require governors to activate them.

What does this mean for state and local leaders? Only the federal government—primarily the U.S. Department of Homeland Security—has the authority to carry out immigration enforcement, but it relies upon partnerships with state and local governments. The most fundamental question for state and local leaders is whether and how actively to cooperate with the Trump administration in its deportation efforts.

As noted above, the response thus far is mixed. At one extreme, Texas is so eager to help that it is offering 1,400 acres in the Rio Grande Valley to build a new detention center. Meanwhile, other state and local officials have said they will not assist ICE—too many to list individually, but including the mayors of Boston, Phoenix, and Denver in addition to other local and state leaders.

In response to such “sanctuary” policies in Trump’s first term, Trump released a 2017 Executive Order declaring sanctuary jurisdictions ineligible for federal grants. In a subsequent memo, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions clarified that the EO applied to grants administered by the Department of Justice and the Department of Homeland Security, and no other departments. Several states and localities sued the Trump administration, and the Biden administration withdrew the executive order in 2021. It’s possible the new Trump administration could reinstate the Executive Order, and several legislators have proposed legislation to similar effect.

Another issue for state and local leaders is managing the downstream effects of any deportation efforts, should they occur and depending upon their magnitude. Previous worksite raids resulted in parents being detained and children being left without caretakers. These actions would have a direct effect on schools, child welfare systems, and other community stakeholders. Local economies and businesses could also be affected by worksite raids and increased deportations. Business leaders and employers in a variety of fields, including construction, agriculture, hospitality, and health care, are nervous.

There also is the issue of where and how to add capacity to detention facilities. The administration is considering re-opening old sites, building new ones, or expanding existing ones in non-border areas with large immigrant populations, such as Denver, Los Angeles, Miami, Chicago, New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C.

In the end, it’s not clear that the Trump administration will be able to deport as many people as it hopes. Even so, it will cause a great deal of damage, in some ways that are immediately obvious and others that will unfold over time. State and local leaders will be on the front lines of the response.

Adie Tomer

The country is about to learn what Builder Trump really wants

It may seem like a distant memory, but back in 2016 most of the country expected then president-elect Donald Trump to be the builder president—in no small part because he told us so. And with the Republicans controlling both congressional chambers, the political stars seemed to aligned for major investments in housing, infrastructure, and domestic manufacturing facilities. Of course, the major domestic construction program never arrived during Trump’s first term of office, leaving states and localities to lead on their own.

This time around, much of the hard work’s already been done. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), and CHIPS and Science Act will give the second Trump Administration a mix of ribbons to cut on previously committed spending and groundbreakings for the new grants they’ll award. There is now far more bipartisan interest in national housing supply shortages and affordability issues. The table is set to see exactly what President Trump and his team really want to build when given the chance.

It’s imperative that states, municipalities, and private companies continue to pay close attention to the actions and signals of the new administration and incoming 119th Congress. Per our Federal Infrastructure Hub, the IIJA and IRA alone authorized more than 200 competitive programs, with tens of billions of dollars in appropriated funding left to award. Understanding what Trump administration officials want—and persuasively making the case for local projects—could be worth millions of dollars for many communities. It’s wise to make calls to newly appointed officials, listen to agency-hosted webinars, and consume any other information that can help make submissions as attractive as possible.

Yet there’s one other lane that shouldn’t be dismissed, especially for mayors, governors, real estate developers, and other entrepreneurs—appealing directly to the President-elect’s builder persona. Major construction projects are legacy-defining for those who bring them to fruition, especially when they’re high-profile, such as a new waterfront neighborhood or a major bridge redesign. It could even apply to unlocking America’s electric future with modern interstate transmission lines. This next year is a golden opportunity to sell the country’s biggest ideas.

This post was originally published on here