Not too long ago, the Wall Street Journal reported on the “hot market” for rare early medical texts, citing last year’s $2.2 million sale (after a $1.2 million high estimate) of a 1555 copy of De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem by Flemish physician Andreas Vesalius at Christie’s. Realistically, the market for these historical encyclopedias, anatomical atlases and surgical manuals is rarely that hot, if only because there aren’t enough early editions of books like Francisco Bravo’s Opera Medicinalia, Nicolò Gervasi’s Antidotarium Panormitanum and William Harvey’s De Motu Cordis to go around. (Only a single copy of Opera Medicinalia, the first medical text printed in the Americas, remains from its original printing.) And it’s worth noting that the mega-million copy of the Fabrica was annotated by Vesalius himself.

There is, however, no shortage of somewhat less rare, less annotated and less well-preserved early medical texts out there at a pleasantly wide variety of price points—good news if you’re looking to start collecting. And if you do start, you’ll be in good company. Rare book dealer Jeremy M. Norman, in a 1985 article in Medical Heritage, wrote that “modern penchant for collecting first and early editions of the classics of medical history” can be traced back to the Father of Modern Medicine, Sir William Osler, whose 7,600-volume library went to McGill University when he died. Other notable collectors include pioneering neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing and Swedish surgeon Erik Waller, whose trove of medical books was so large that his Wikipedia parenthetical is not ‘doctor’ but ‘collector.’

You don’t have to be in medicine to start buying historical medical texts, though it probably makes building a library that much sweeter. Renowned cerebrovascular neurosurgeon Dr. Eugene Flamm has been collecting for six decades—his first acquisition was a Vesalius he bought while a resident, and that work kicked off a life-long passion for collecting antiquarian books that document the history of anatomy, medicine and surgery and, more broadly, incunabula and books with interesting provenance. He sees the significance of early medical texts as multifaceted: historically important, scientifically important and culturally important.

“To understand what was done with all good intentions for patients three hundred, four hundred or five hundred years ago gives one insight into our current accomplishments and shortcomings,” he told Observer. “The books, of course, provide no information for carrying out surgery today, but they do keep one informed and honest about the limitations of complex surgery, even now. Aside from all that, they are often beautiful objects from a period when printing sprang up fully grown, seemingly without an infancy.”

The past-president of the bibliophiliac Grolier Club in New York has over time amassed a collection of thousands of books documenting what he calls the “scientific and intellectual milestones” of mankind. Books, he said in no uncertain terms, should be regarded as an intellectual investment, not a financial one. Fledgling collectors ought to first be interested in a topic and then explore it according to their means and desire to learn.

But while many collectors with Brobdingnagian bookshelves bequeath their libraries en masse to universities or other institutions to cap off a personal quest for knowledge, Dr. Flamm, who is 88 years old, has different ideals about the future of his collection.

“It has always been my wish to return my collection to the marketplace so that younger collectors can have an opportunity to acquire early books and live with them,” he said. A Christie’s auction that opens online on January 14 and runs through January 28 is, he added, the first step toward carrying out that plan. “If all books are institutionalized, we will annihilate the spirit and importance of the collector.”

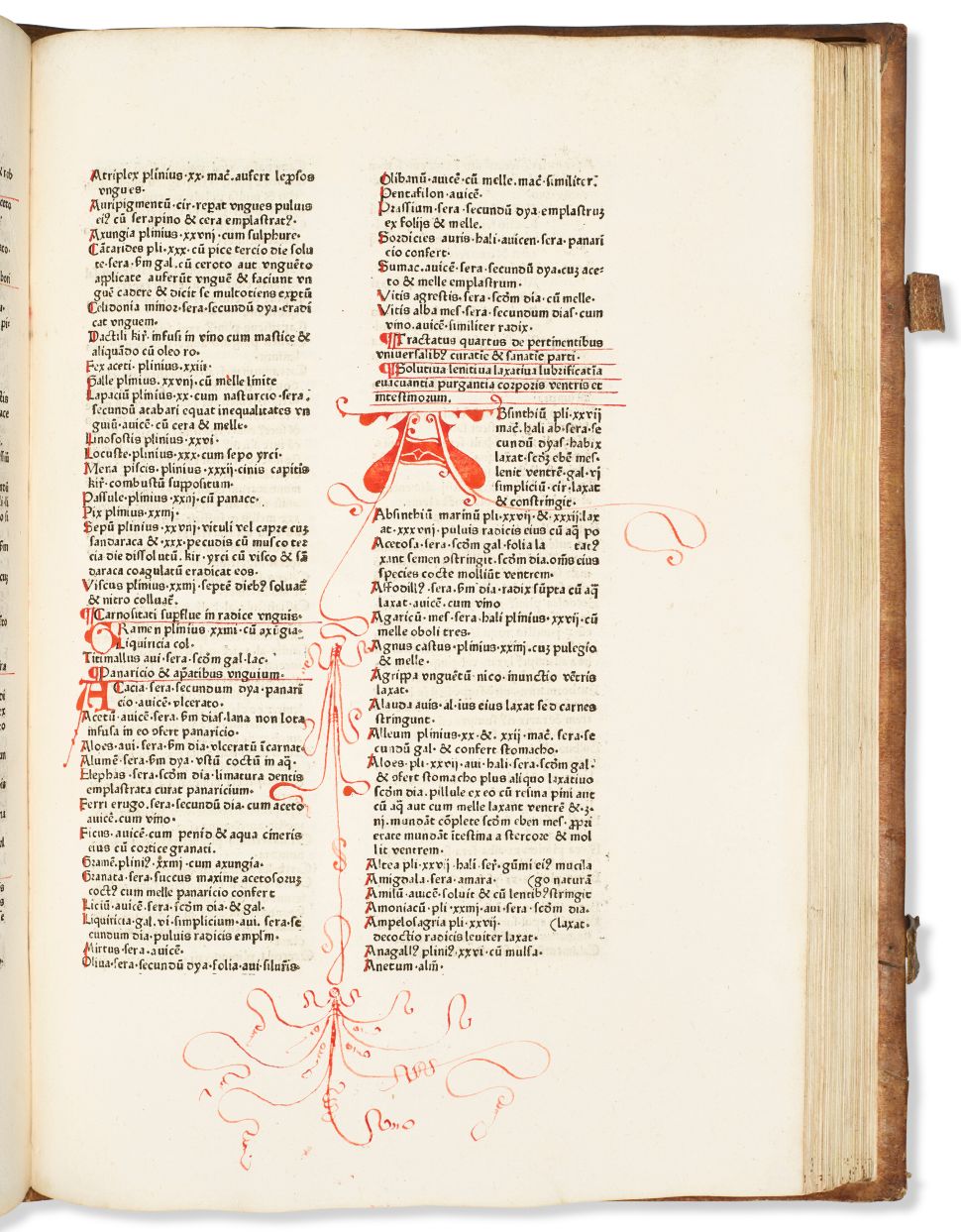

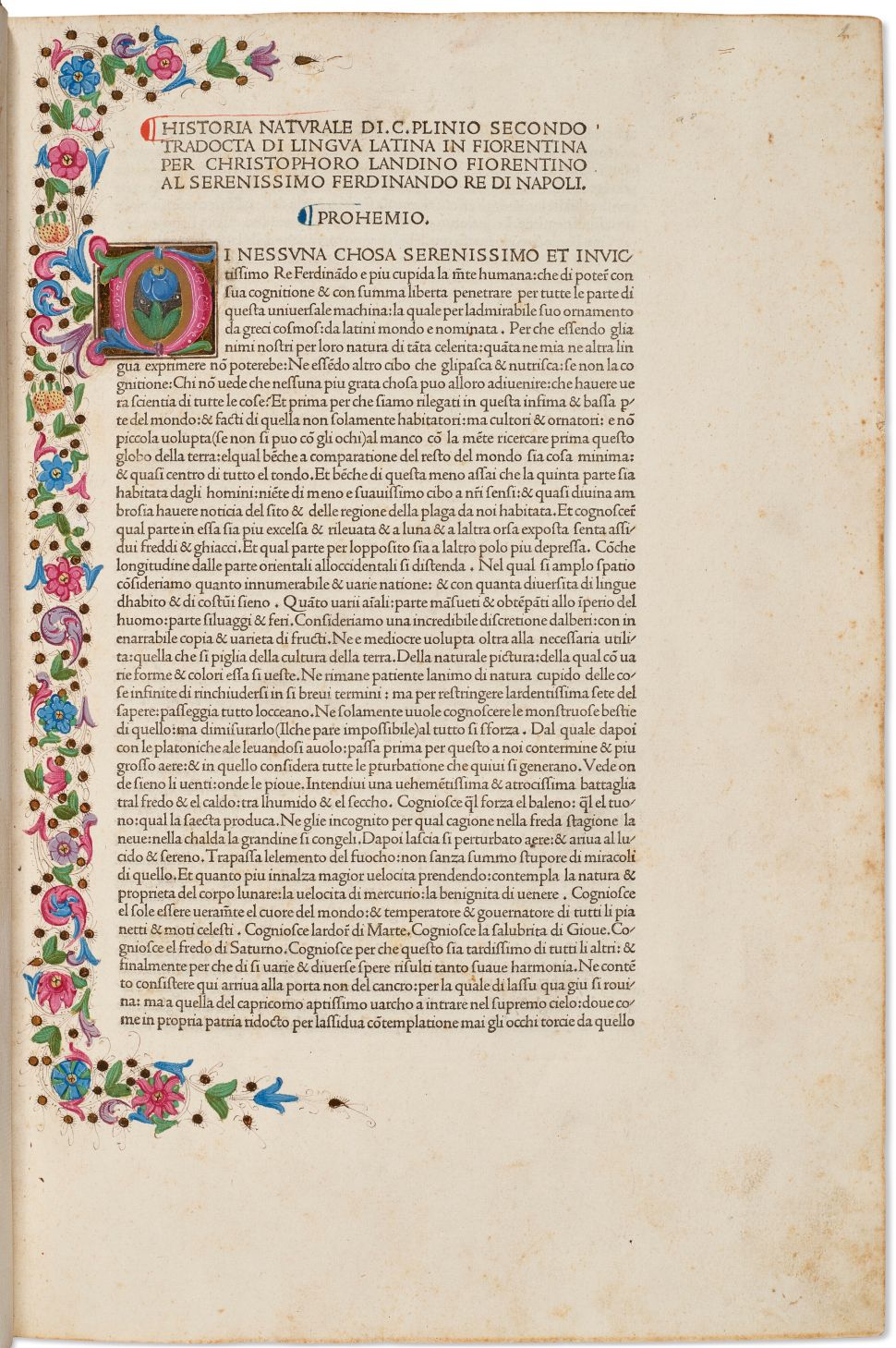

Among the 230 lots in the Fine Printed Books and Manuscripts including Americana sale will be Incunabula from the Collection of Eugene S. Flamm: early printed examples of encyclopedias, bibliographies, histories, medical illustrations, scientific works and other texts. There’s the first and only edition of Ludovicus’ Trilogium animae (high estimate: $12,000), with a woodcut of the brain by artist Albrecht Dürer. There’s the first illustrated edition of Mundinus’ Anathomia corporis humani (high estimate: $20,000), a work that re-introduced the concept of anatomical dissection. And there’s Jacobus de Dondis’ Aggregator, sive De medicinis simplicibus (high estimate: $120,000), which is one of the earliest texts dedicated entirely to medicine.

Other works from Dr. Flamm’s collection going on the block include Pliny the Elder’s Historia naturalis (the third edition has high estimate of $15,000; the first Italian edition has a high estimate of $150,000), Albert Magnus’ Philosophia pauperum (high estimate: $20,000) and Bartholomaeus Anglicus’ De proprietatibus rerum (high estimate: $100,000).

When I ask Dr. Flamm, who has curated several public exhibitions of works from his collection at venues like Johns Hopkins University and the Grolier Club, if there’s a dream text he’d love to acquire, his answer is coy but will resonate with passionate collectors across all categories: “The list is too long to send.”

This post was originally published on here