There is no show in history more obsessed with its own lore than Saturday Night Live. Almost every week the long-running sketch show is sprinkled with returning alumni and jokes that reference the show’s illustrious and controversial past: its social club status for the great and good of New York; the drug-fuelled deaths of its brightest lights such as John Belushi and Chris Farley; the superstars it created in Eddie Murphy, Bill Murray, Adam Sandler, Will Ferrell and Tina Fey, to name but five of hundreds.

SNL is so fabled that it’s already inspired scores of documentaries and numerous scripted TV shows based on it, including 30 Rock and Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. In February, there will be a three-hour primetime special celebrating the show’s 50th anniversary, an event likely to be more starry than the Oscars (at a similar event for the 40th anniversary, Taylor Swift, Paul McCartney and Prince formed an impromptu band to entertain the afterparty). At the centre of it all, Lorne Michaels, the show’s inscrutable Canadian executive producer, who has become the most powerful man in American comedy, yet famously is incredibly difficult to make laugh.

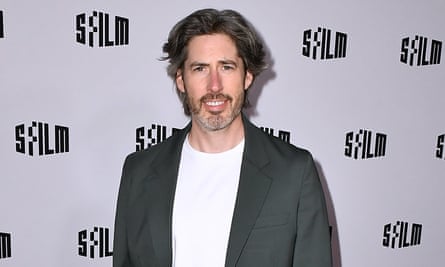

You’ll find few people more enamoured of the legend of SNL and the man in charge of it than Jason Reitman. In 2008, Reitman was one of the buzziest directors working in Hollywood, having just had a surprise hit with the indie film Juno. He could have worked with pretty much anyone (and later did, with George Clooney on Up in the Air and Charlize Theron in Young Adult), but what he really wanted to do was fulfil his boyhood dream of writing sketches for Saturday Night Live. As a child, he had grown up around the original cast. His father, Ivan Reitman, was the director of National Lampoon’s Animal House and the original Ghostbusters films and Jason would follow him around on set. John Belushi gifted him a blanket as an infant, Bill Murray described him as a pain in the ass. SNL runs in his blood.

Michaels acquiesced and let him be a guest writer for a week, pitching sketches for a cast that at that time included Amy Poehler, Kristin Wiig and Maya Rudolph. He pitched three sketches and managed to get one on the air: Death By Chocolate, in which that week’s host, Ashton Kutcher, plays a murderous bar of Hershey’s, knifing strangers in back alleys. “It was one of the great weeks of my life,” Reitman tells me.

Being on set that week gave him the idea for a film about the very beginnings of SNL, before it was a TV institution. “What I have always been interested in is the moment when genius comes into the universe,” he says with no concern for accusations of bombast. “What is it like in the room when Paul McCartney writes Yesterday? Does it feel like something special happened, or is he just fucking around writing a song on a napkin? With SNL, it’s this magic trick, the choreography of the sound people, camera people, wardrobe people, how they operate together like a ballet in this tiny space in an office building in New York City. It’s insane.”

Now, 15 years later, Reitman is finally making his obsession a reality with the release of Saturday Night, a movie about trying to get the very first episode of SNL on the air in 1975. The film hits familiar beats: the network suits who are told they don’t understand the avant garde genius they’re witnessing; the pioneering comics who struggle to be contained by the constraints of television or, indeed, real life. But Reitman’s twist is to make it a thriller, more like watching Speed or Taken than a traditional biopic.

It begins 90 minutes before they’re due to go to air and everywhere chaos reigns. Belushi’s contract isn’t signed and he’s having punch-ups with Chevy Chase in the makeup room, the writers are bullying Jim Henson because they think his Muppets are stupid and the show’s effervescent comedic actor Gilda Radner is flying through the studio on a camera crane. There’s no script, no set and NBC is threatening to play a rerun of Johnny Carson instead. Will they manage to get the show on the air? The film answers the question in real time with Jon Batiste’s tick-tock score, recorded live on the set while the movie was being filmed, ramping up the tension.

Trying to interview Reitman and the film’s cast in a hotel in Toronto, there’s a similar degree of time-sensitive pandemonium. In a maze of hotel corridors I am shepherded, with no explanation, in and out of rooms where a different personality awaits – the calm of Reitman, say, or the wisecracks of comedic actor of the moment Rachel Sennott (Bottoms, Shiva Baby), playing SNL writer and Michaels’s first wife Rosie Shuster, or the serious thespian chops of Cory Michael Smith (who does an eerily accurate turn as Chase). Sometimes I’d be left completely alone in the room with an actor and given an hour – in other instances I get 10 minutes and bizarrely have four cameras trained on me.

One thing that’s clear is how much the cast have bonded. When I ask them about meeting Michaels while they were shooting, they can only try to make each other laugh. “What he said to me was: ‘Sir, get off my lap. I don’t know you, and I hope your career drowns,’” says Dylan O’Brien, who plays Dan Aykroyd.

There’s an obvious metaness to the whole project, which Reitman embraced – after all, just like Michaels, he too is trying to corral a group of excited, vulnerable young actors with varying degrees of experience into making something slightly unknown. So he let them run riot on the set and improvise at will.

“We didn’t have trailers. We had a big living room with tons of 70s furniture, old records, old movie posters on the wall, board games and ping pong tables,” says Gabriel LaBelle, who having just played a thinly veiled Stephen Spielberg in the director’s latest film, The Fabelmans, now takes a turn as the famously inscrutable Michaels. “Jason was so smart in making that happen and building the camaraderie between this cast.”

“We were just kind of free to do whatever the fuck we wanted,” says the British actor Ella Hunt, who plays Gilda Radner. “In one scene we’re running like banshees down the hall, and I took a massive pile of scripts and threw them into the air. It just felt like nothing was precious, and all of the mistakes were welcome.”

For the cast of Saturday Night, it meant they had the odd feeling of playing characters who were household names in their own homes. “My dad’s doing a watch party with his college friends,” says Sennott, whose background is in more risque indie films. “I’m just excited because he’s been watching me give blowjobs left and right. This is one he can watch with his friends and relax.”

Sennott, who is currently experiencing a moment of cultural explosion that the debut SNL cast might be familiar with, has appeared in both A24 cult hits and Charli xcx videos. Her college portrayal of Shuster gives the film a different centre of gravity to previous accounts of its history. Shuster is portrayed as an ego masseuse, sharp writer and general troubleshooter, who flirts with the stars and organises the big dreams of her husband into something that can get on the air.

Sennott spent time with Shuster before shooting: “Just hearing her voice, her laugh, and how she was so undaunted in the face of chaos and all these challenges – it was exciting to play, because that’s not what I’m like at all.”

after newsletter promotion

In contrast to Sennott, Hunt had never attempted comedy when she auditioned for Gilda Radner, the first person to be cast on the original SNL. “You’d think an English girl doing a brassy Detroit accent sounds like something out of a horror movie,” she tells me. “But she’s like me. Her goofiness feels very familiar to me in the way in which I act with my family.”

In real life, Radner had to negotiate endless sexism on set: Belushi would famously howl that “women aren’t funny” backstage. Hunt had to embody the way Radner would disarm men who crossed her, while still appearing like she could take a joke. “When I watch Gilda navigating that space, it just feels so virtuosic to me, she’s playing the room on so many levels. Thinking about Gilda and [fellow SNL female alumni] Jane Curtin and Laraine Newman occupying that space and just how many of the men in the room really didn’t think that they should be there, the odds were so stacked against them.”

Once he’d settled on the cast, Reitman sent them all emails telling them not to spend too much time watching old footage of the people they were portraying, to trust that they have the essence of the person in them. It was a huge vote of confidence … and almost every cast member completely ignored it.

“For about two months I would exclusively watch Chevy Chase,” says Michael Smith, a charming and self-serious leading man whose personality couldn’t be more at odds with the wisecracking Sennott. “I just watched him over and over and over until I felt like I was beginning to have his instincts – things like the way he blinks emphatically after a line to cue people to laugh.”

Chase is one of the most cocksure figures of the 1970s, but Smith wanted to understand what he was like just before that moment: “We all know confident, charismatic Chevy Chase, who has swagger. But this is the night before the world met him. He is closer to me: he’s hopeful and optimistic and a hustler and a little nervous, maybe feeling a little fraudulent. He famously had a humiliating first appearance on Johnny Carson where he was so nervous. Everybody laughed at him. That was helpful, seeing this vulnerable, nervous guy.”

The final film is chaotic and includes so many memorable performances that it’s almost impossible to mention them all: Nicholas Braun’s double acting duties as Andy Kaufman and Henson; JK Simmons playing the old school entertainer Milton Berle; Willem Dafoe as the NBC executive willing it all to fail; standup Lamorne Morris, the film’s most obvious comic actor, as Garrett Morris, SNL’s first Black cast member (no relation); and Cooper Hoffman (son of Philip Seymour Hoffman) as the overstretched young executive Dick Ebersol.

Some reviews have criticised the film’s lack of answers: it presents disaster after disaster and then somehow everything works out. It’s true that Reitman probably believes a little too much in the magic of the show, but the film succeeds in creating a taut chaos, never quite letting you settle into what’s going on, and is filled with new little titbits that superfans like Sennott’s father will love (for example that Billy Crystal was still smarting for years after his sketch got cut from the opening episode).

But I wonder how the film will land in the UK, where SNL doesn’t have such mythical status. Will audiences care that much about whether Belushi signs his contract? “SNL is just a location, but the film is about that adrenaline,” says Reitman. “Everybody knows what it’s like to put on a show, even if it’s a talent show or a high school play. At some point every person has tried to do something, where 30 minutes before you’re going: ‘How the hell is this ever going to come together?’ And then here’s a way that we coalesce, where enemies become friends and you make something. And I wanted to make a movie that really captured that concept.”

Reitman is clearly still enamoured of the magic of live TV, and giddy at the thought that he might now be the magician – taking a real set, an improvising cast, a live band and 80 microphones and trying to do what Michaels did 50 years ago: get the show on the road.

Saturday Night is in cinemas from 31 January.

This post was originally published on here