Will Trump Wage ‘No New Wars’?

Lessons from the past about Trump as commander in chief.

President Donald Trump salutes as he walks out to greet Argentine President Mauricio Macri and his wife, Juliana Awada, at White House in Washington, D.C., on April 27, 2017. Jim Watson / AFP via Getty Images

The U.S. president has significant latitude to use military force even in the absence of congressional authorization and even when such action would violate international law. Through its military interventions in the Middle East since Oct. 7, 2023, the Biden administration has both further eroded the existing guardrails constraining presidential war powers and possibly bequeathed a new conflict with the Houthis to his successor.

Despite President-elect Donald Trump’s oft-deployed slogan of “no new wars” and claims that United States was at peace during his first administration, Washington both engaged in new conflicts and expanded and intensified existing ones without fresh congressional authorization under this leadership between 2017 and 2021.

The U.S. president has significant latitude to use military force even in the absence of congressional authorization and even when such action would violate international law. Through its military interventions in the Middle East since Oct. 7, 2023, the Biden administration has both further eroded the existing guardrails constraining presidential war powers and possibly bequeathed a new conflict with the Houthis to his successor.

Despite President-elect Donald Trump’s oft-deployed slogan of “no new wars” and claims that United States was at peace during his first administration, Washington both engaged in new conflicts and expanded and intensified existing ones without fresh congressional authorization under this leadership between 2017 and 2021.

Trump’s first four years in the White House revealed a commander in chief who, while erratic, had certain tendencies with respect to the use of military force. Due in part to his transactional nature, Trump was generally skeptical of large-scale U.S. military presence overseas and the value of U.S. alliances and partnerships. He was prone to one-upmanship with respect to U.S. military action—launching attacks in part because prior presidents had refrained from them.

Given the wide freedom of action afforded the commander in chief and the might of the U.S. military, decisions by the incoming president on the use of force could be globally consequential. In light of those stakes, it is worth revisiting Trump’s track record on the use of military force during his first term in office.

When Trump took office in 2017, he inherited a narrowly focused U.S. military mission in the complicated battle space of the Syrian civil war. Despite broader policy objectives, his immediate predecessor, President Barack Obama, had limited direct military force in Syria to fight the Islamic State, rejecting calls from his advisors to attack Bashar al-Assad and enforce the administration’s self-imposed “red line” on chemical weapon use.

Despite a monthslong review of the Obama administration’s campaign plan to fight the Islamic State, the Trump administration’s most notable initial shift was redubbing “ISIL” to “ISIS.” Although the destruction of the Islamic State’s physical “caliphate” and the killing of its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi ultimately occurred on Trump’s watch in 2019, mostly his administration continued Obama’s counterterrorism playbook.

However, Trump had cause to revisit Obama’s red line early in the administration when Assad’s forces launched a deadly sarin attack on Khan Shaykhun in 2017, killing dozens of civilians, including children. According to two of Trump’s children, Trump decided to strike in retaliation after seeing images of Syrian children fatally poisoned. Trump’s statements also suggested that he wished to one-up Obama, critiquing his predecessor for failing to enforce the red line.

Yet, Trump’s original retaliation plan wasn’t implemented. According to reporter Bob Woodward and later partially confirmed by Trump, Trump called Defense Secretary Jim Mattis seemingly to demand the assassination of Assad, shouting, “Let’s fucking kill him! Let’s go in. Let’s kill the fucking lot of them.”

Woodward reports that Mattis told his subordinates, “We’re not going to do any of that. We’re going to be much more measured.” (Trump has denied this account of events.) And so, the U.S. retaliation was more measured, consisting of airstrikes on the Shayrat airbase, which was allegedly used to conduct the fatal sarin attack.

Although Trump was enthusiastic about killing terrorists, he had an aversion to anything he perceived as nation-building and was deeply skeptical of large-scale troop deployments. These sentiments contributed to his precipitous decision in December 2018 while on a phone call with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan—to withdraw all U.S. forces from Syria. The sudden move led to the Mattis’s resignation.

Despite Trump’s announcement, U.S. forces remained in Syria as officials in his administration walked back the decision of total withdrawal. This was partly due to Trump’s intermittent focus on the matter and the separate, more ambitious Syria agendas of his underlings, some of whom were more interested in using U.S. troops to counter Iran rather than the Islamic State. Later, in October 2019, Trump did in fact partially pull back US troops in northern Syria at the urging of Turkey.

Trump was also convinced by officials within his administration and members of Congress to retain some U.S. forces in Syria to “keep the oil.” These advocates appealed to Trump’s long-stated desire for concrete material benefit from U.S. military deployments. The reality that “keeping the oil” was both impractical and illegal did not matter.

Trump’s policy shift on Iran was more dramatic. Obama left office having constrained Iran’s nuclear program through a painstakingly crafted multilateral agreement while Tehran’s paramilitary proxies in Iraq observed a wary truce with U.S. forces as they both fought the Islamic State.

After firing many of the supposed adults in the room in his administration, Trump pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal and reimposed sanctions to apply “maximum pressure.” These actions upended a tense modus vivendi in Iraq. With Tehran no longer restraining them, Iran-backed paramilitary groups based in Iraq resumed attacks on U.S. forces in 2018.

Even so, Trump was not eager to engage in a major conflict with Iran. After the Iranian downing of a U.S. drone over the Persian Gulf in 2019, Trump ultimately refrained from the retaliatory attack advocated by his hawkish advisors—reportedly due to cautionary counsel from Tucker Carlson. Trump also refrained from attacking Iran in response to Iranian missile strikes on oil facilities in Saudi Arabia. Despite publicly blaming Tehran for the September 2019 attack, Trump announced he would “like to avoid” conflict with Iran and indicated interest in a new nuclear deal with the Islamic Republic.

Yet, the Iran hawks surrounding Trump ultimately convinced him to take significant and provocative military action against Iran. According to reporting by Jack Murphy and Zach Dorfman, officials such as then-CIA Director Mike Pompeo began planning to kill Iranian Gen. Qassem Suleimani as early as 2017. Continuing attacks on U.S. personnel in Iraq from Iran-backed forces in late 2019 provided justification; he was ultimately killed in January 2020.

What exactly Trump’s advisors told him about the likely Iranian response to Suleimani’s killing is unclear. But he does not seem to have expected the retaliatory ballistic missile barrage that Iran unleashed on U.S. troops in Iraq. Certainly, he sought to immediately downplay the attack in an effort to de-escalate with Iran—tweeting out “all is well” following the strikes. Trump has continued to minimize the injuries to U.S. troops—more than 100 service members with traumatic brain injuries—as headaches. Indeed, Pentagon officials were reportedly concerned that awarding Purple Hearts to wounded troops would undermine Trump’s narrative.

Such predictable Iranian retaliation was the reason that both the Bush and Obama administrations had refrained from killing Suleimani.

The Trump administration, Iran hawks in Congress, and the commentariat have subsequently tried to cast Suleimani’s killing as “restoring deterrence” vis-a-vis Iran. Such spin obscures not only Iran’s immediate ballistic missile attack on U.S. troops, but also further attacks on U.S. forces in Iraq by Iran-backed groups during the remainder of Trump’s term, some of which resulted in U.S. fatalities.

In Yemen, the Obama administration gave Trump a counterterrorism campaign against al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and a conflict with Houthi militants in which the United States was not directly fighting (apart from a single strike on Houthi radar facility in late 2016).

Still, the United States was providing essential arms, maintenance, and spare parts for the ruinous bombing campaign waged by a Saudi Arabia-led military coalition. The coalition’s penchant for using U.S. weapons to bomb Yemeni civilians—and its failure to improve targeting over 18 months—led the outgoing president to suspend precision-guided munition transfers to Saudi Arabia after its warplanes bombed a funeral in Sanaa, killing more than 100 civilians.

Among Trump’s very first military actions as commander in chief was greenlighting a rare and risky commando raid against AQAP in Yemen that the outgoing Obama administration had forgone. The U.S. assault alongside forces from the United Arab Emirates resulted in numerous civilian casualties—including children—and the death of a U.S. Navy SEAL.

Trump also promptly reversed Obama’s lame-duck arms sales suspension. While he had little interest in direct U.S. military engagement in the Saudi-Houthi conflict, Trump was all too eager to sell weapons to Riyadh.

Although his administration would later seek assurances from Saudi Arabia that it would use U.S. weapons consistent with the law of war, the desire to sell weapons overshadowed accountability. After Saudi Arabia used U.S.-supplied precision-guided munitions to attack a school bus full of Yemeni children in 2018, Trump characterized the strike as a “horror show” and candidly admitted that the Saudis “didn’t know how to use the weapon.”

When the State Department’s inspector general investigated U.S. arms sales to Saudi Arabia and the Department’s efforts to limit civilian casualties, Trump fired the inspector general and the Department later suppressed the investigation’s full results.

There is no crystal ball to predict how Trump will wield his power as commander-in-chief. The degree of Trump’s personal involvement in policy, who he chooses to listen to, and the willingness or ability of his team to temper outlandish proposals are among the many sources of uncertainty.

Nonetheless, his record from 2017 to 2021 and subsequent statements—particularly following the 2024 election—could offer a preview of his agenda as commander in chief.

Trump is no dove, and he is fond of issuing blustery military threats. (His recent comments regarding potential military action with respect to Greenland and Panama appear to be mostly trolling and bluster—for now.) And though such threats alone may harm U.S. interests, he has often lacked follow through, and it seems he would avoid intentionally involving the United States in a major armed conflict. Indeed, he may again seek to remove U.S. forces from conflicts in Syria, Somalia, and potentially Iraq.

Yet, Trump’s instincts should provide only limited comfort to those concerned about further U.S. wars. His willingness to escalate U.S. bombing campaigns in Somalia and Afghanistan before moving to withdraw U.S. forces could provide a template for how he will handle the conflict with the Houthis he may inherit. His track record with enabling Saudi Arabia’s military campaign in Yemen suggests that he is happy to fuel other countries’ wars, no matter how they are waged.

And, as with the Suleimani strike, Trump may act heedlessly without fully appreciating the consequences of his actions—particularly if encouraged by his advisors. In this respect, Trump’s musings during his first term about missile strikes on Mexican drug cartels are particularly worrying.

By casting doubts on whether the United States would come to the defense of allies and partners, Trump may encourage adventurism by revisionist rivals as well as nuclear hedging by countries such as South Korea, which may decide that it is time for a level of self-reliance they have not previously considered necessary.

Trump’s boosters sometimes laud his unpredictability as a virtue that keeps foreign adversaries off balance and deterred. Whether it is a virtue or not, the commander in chief of the world’s most powerful military will again be unpredictable and likely even less constrained than he was during his first term given the weak guardrails on use of force by the U.S. president.

Brian Finucane is senior advisor in the U.S. program at the International Crisis Group. He is also a non-resident senior fellow at the Reiss Center on Law and Security at NYU School of Law and a member of the editorial board of Just Security. Prior to joining Crisis Group in 2021, he served as an attorney advisor in the Office of the Legal Advisor at the U.S. State Department. X: @BCFinucane

More from Foreign Policy

-

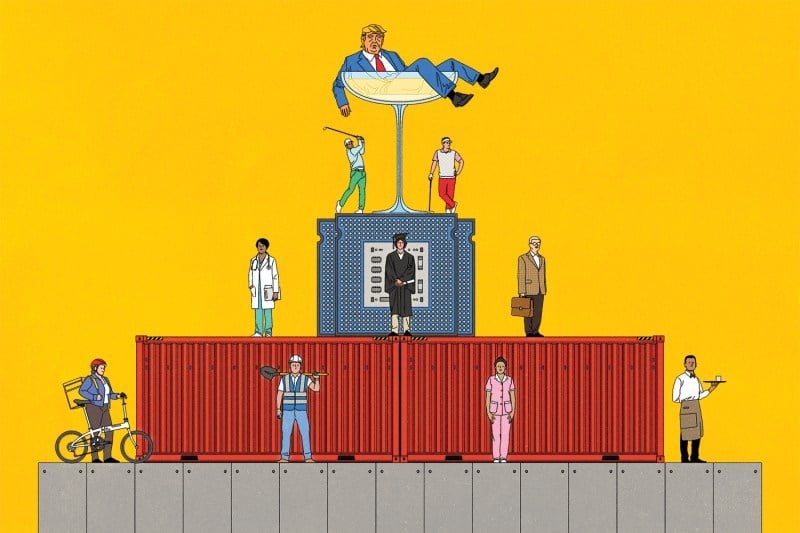

An illustration shows three tiers of classes, working class on the lowest with a bike messenger, a construction worker, a hotel worker, and a waiter; the second tier shows the professional-managerial class with a doctor, a graduate, and a man with a briefcase; the top layer shows two men golfing. Between them is a Donald Trump in a champagne coupe. America Is Locked in a New Class War

Money and education no longer explain voting patterns.

-

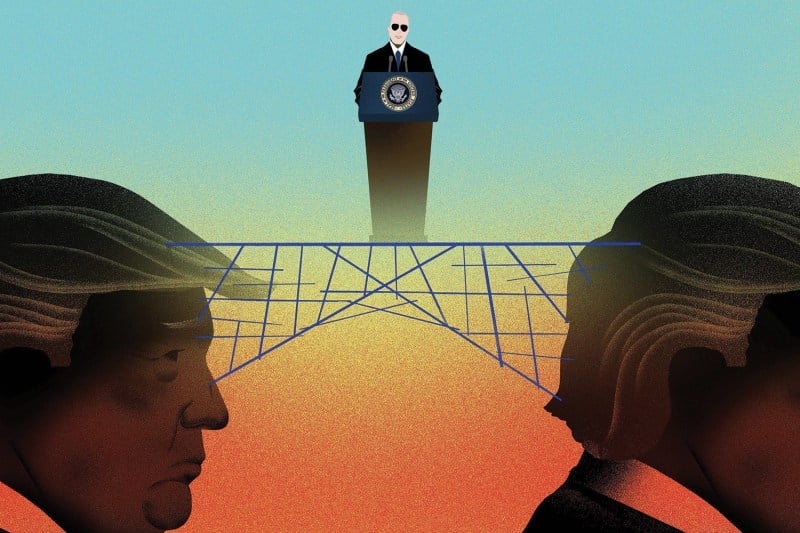

An illustration shows Joe Biden at a lecturn on a bridge spanning a chasm with two heads of Donald Trump in profile forming the base of the bridge. Why Biden’s Foreign Policy Fell Short

The White House never met its own grandiose standards.

-

An illustration shows Donald Trump smiling zanily with yellow hair flying one direction and a red tie snaking through his ears and around his head wildly. Does the Madman Theory Actually Work?

Trump likes to think his unpredictability is an asset.

-

An illustrations shows the silhouette of Donald Trump with a face filled with pricetags. Trump Is Ushering In a More Transactional World

Countries and companies with clout might thrive. The rest, not so much.

This post was originally published on here

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber?

.

Subscribe

Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username |

Log out