In 1628, Shah Jahan acceded to his father’s throne to become the fifth padishah of Hindustan. The event is described in the text of the Padshahnama, an official chronicle of the reign, and it is also depicted in a painting commissioned to accompany the words. It shows the emperor receiving his three eldest sons in a glittering court scene.

The centre of the image, the focus that draws the viewer’s eye, is a young Dara Shukoh bowing low before his father; Shah Jahan’s arms are extended too, to clasp his beloved eldest son’s shoulders. It is a tender moment, clearly recognisable to any Indian who has ever bent down before a parent or grandparent as a gesture of respect. But the elite audience this painting was made for would not have read it the way we can today, with our knowledge of history: Aurangzeb standing on the margins of his father’s affection, foreshadowing the destruction of his family. For us, the image transforms from one of celebration to one of foreboding.

It is this imaginative potential that contemporary illustrated histories, like The Book of Emperors (co-authored by Nikhil Gulati and myself) and The People of the Indus (by Nikhil Gulati, with Jonathan Mark Kenoyer) draw on. Illustrated histories aren’t a new format in English, especially outside of India: kids (and adults) have giggled through the irreverent art in the Horrible Histories series or enjoyed the photographs that fill publisher Dorling Kindersley’s handsome volumes, and there are newer attempts to use the medium of comics to make history engaging, like The Middle Ages: A Graphic History by Eleanor Janega and Neil Max Emmanuel.

This article is NOT paywalled

But your support enables us to deliver impactful stories, credible interviews, insightful opinions and on-ground reportage.

In India, though, most people first encounter history in school, where engaging with the people of the past takes a back seat to the memorisation of names, dates, and lists, all without sufficient context. We view coins, sculpture, buildings and artefacts outside of the worlds that produced them, which often elides what made them significant in the first place. This contextless-ness renders us unable to recognize that the past was populated by real people making decisions in varied circumstances that are far removed from our own.

Illustrated histories present an opportunity to fill in these missing details, to make the story of the past more accessible, and more interesting. These works are written for audiences of all ages to whom they present history in a way that invites engagement instead of intimidating the reader. At a time when the discipline of history is under siege, with misinformation running rampant even as funding for research dries up, vividly illustrated narrative accounts help demystify the past and push back against misinterpretation and misrepresentation—two things that both the history of the Indus Valley Civilization and the Mughal Empire seem especially prone to today.

Also read: Deleting history from NCERT textbooks is lying to children. It’s also betraying parents

Beyond heroism and villainy

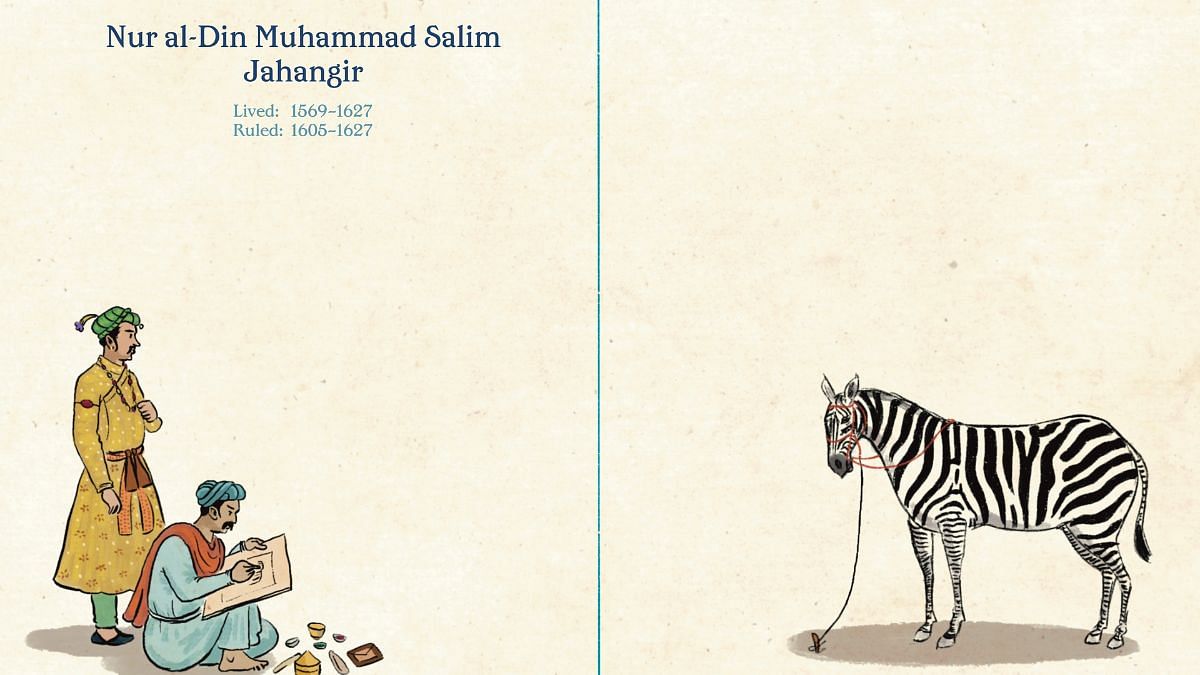

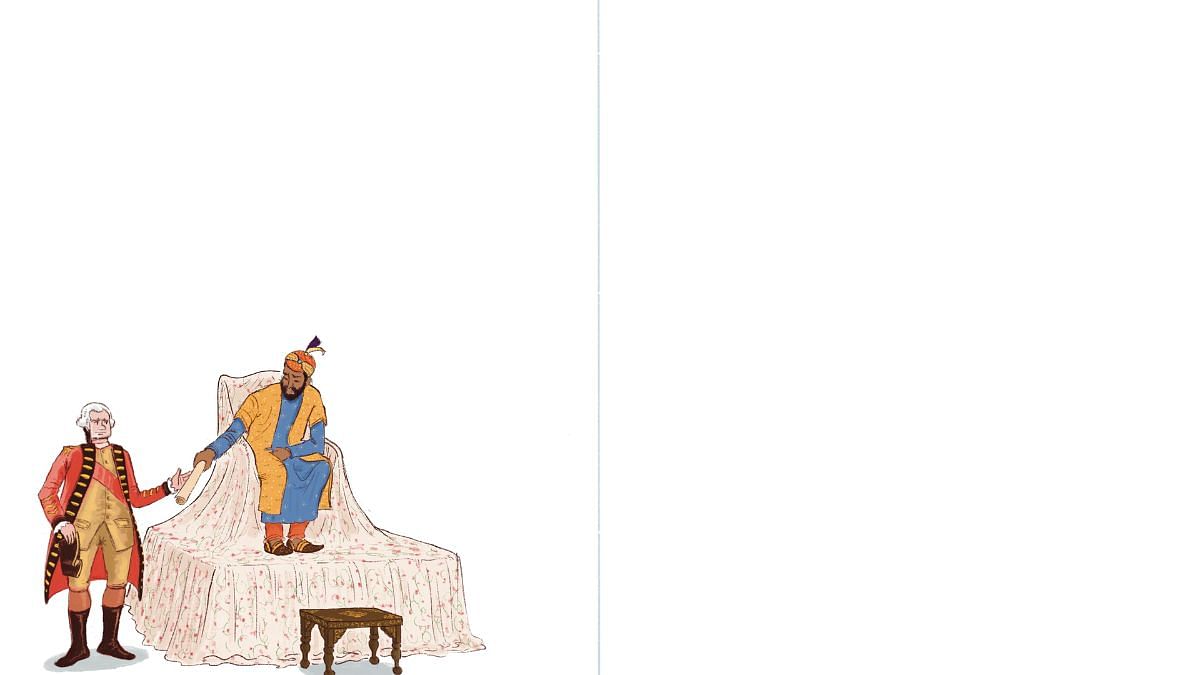

In The Book of Emperors: An Illustrated History of the Mughals, the emperors and those around them are given purpose and personality rather than being reduced to one-dimensional caricatures as they often are. Each emperor portrait epitomises a quality or a trait that most represents its subject: Jahangir peers over an artist’s shoulder as he draws a zebra; Shah Jahan stands with his back to the reader, watching, across the water, a white marble tomb be built; Shah Alam is laid low by despair as he hands the diwani over to a looming Robert Clive.

The narrative chapters on each emperor are interspersed with double-page spreads that draw inspiration from Mughal art: we see the Mughal garden full of fruit and flowering trees, a functional space for both pleasure expeditions and court business; we see the marketplace bustling with traders hawking their wares to merchants both Indian and foreign; we see the emperor ride his elephant as he pursues his quarry in a qamargah-style hunt, surrounded by beaters, beasts and spectators. We see the individuals who made up the empire in context, as actors whose worldviews and ideals were shaped by a variety of influences.

For ancient or early medieval India, such context and individuality are harder to find, and must be mined from a variety of sources, from the archaeological to epigraphs and literature. And when we go back thousands of years to the Indus Valley Civilization, all we have are the remnants of the lived-in spaces and objects found in them—seals, toys, jewellery, utensils, and weapons. Seeing them in a sterile museum display case, it is easy to forget that they once belonged to someone.

To bridge this distance, The People of the Indus foregrounds the people of the Indus, imagining them into being in its first few pages in a wordless sequence that shows a family packing up their belongings and leaving for the big city. Veering between the present-day and the past, it places the physical remnants from the display-case back into the world they come from. Five thousand years may separate us from the people who made these objects, but through the medium of comics, the years fall away. Suddenly, we see traders using weights, children playing with toys, coppersmiths plying their trade, and hunters with their bows out to find food to feed their families. Instead of faceless entities we can project our own ideas onto, the people of the Indus become real, and we build a sense of kinship and understanding that transcends time.

Illustrated histories, with their potent combination of narrative and art, is an effective way of getting us to imagine the past in minute detail, giving us a visual reference for what life would have looked like hundreds or thousands of years ago. Crucially, they also put people front and centre, nudging us into understanding that the people of ancient India and medieval India were animated by the same impulses as us: love, greed, ambition, and the desire to make a mark on the world. This kind of work feels especially important to produce in our polarised times, when historical people are turned into black–and-white figures of either heroism or villainy, and the past is weaponised to justify present-day violence.

By placing history and historical figures in context, illustrated histories can highlight our continuity with the past, even as they immerse us in worlds that are very different from our own. In this way, they can help make the argument for why the past is relevant, and worth remembering with empathy rather than judgement.

Ashwitha Jayakumar is a writer of narrative history for readers of all ages. She has an MA in Medieval Studies from the University of Leeds and is the author of The Book of Emperors: An Illustrated History of the Mughals and Incredible Indians: 75 People Who Shaped Modern India. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

This post was originally published on here