This post was originally published on here

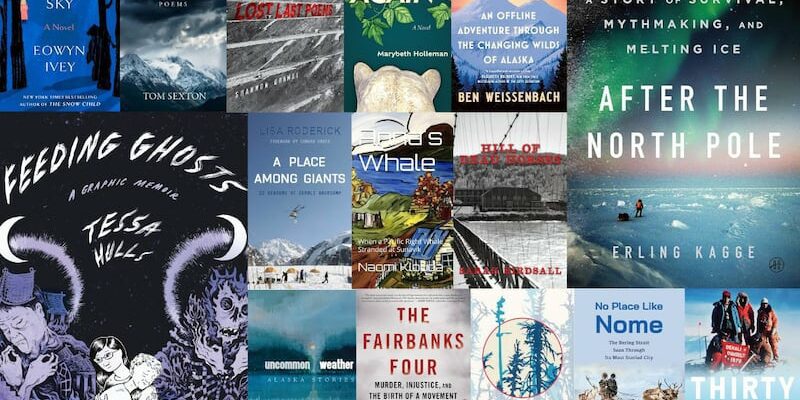

Anchorage Daily News book reviewers Nancy Lord and David James present the 2025 works that they found most memorable and meaningful. Their lists include poetry, works of fiction, adventure stories, a Pulitzer-winning memoir and multiple books that interrogate the changing nature of the North.

Nancy Lord’s favorites of 2025

Memoirist Patricia Hampl has said it well: “If nobody talks about books, if they are not discussed or somehow contended with, literature ceases to be a conversation, ceases to be dynamic. … Without reviews, literature would be oddly mute in spite of all those words on all those pages of all those books. Reviewing makes of reading a participant sport, not a spectator sport.”

I’m fortunate to be part of the conversation. This year, from the 31 books I’ve reviewed on these pages, I’ve selected the seven works of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry that I’ve most enjoyed and am pleased to recommend to other readers.

Fiction

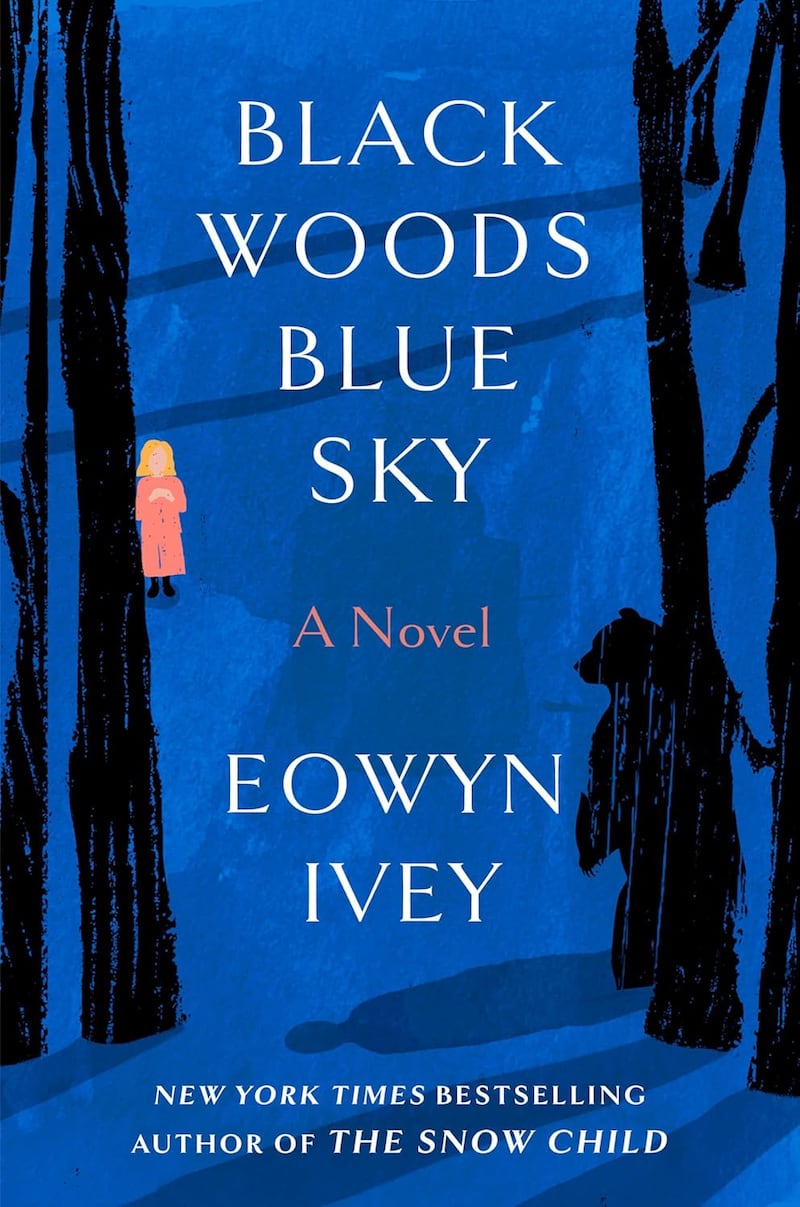

By Eowyn Ivey; Random House, 2025; 306 pages; $29.

Eowyn Ivey, the well-known Alaska author and Pulitzer Prize finalist, has returned to her fascination with fairytales to set her latest novel again in the landscape of “The Snow Child.”

The story, told in alternating viewpoints, involves the restless mother of a 6-year-old, her child, and a strange man who lives alone in a mountain cabin. While each character is presented as a complex, relatable personality, the child, Emaleen, holds the center of the narrative. Cleared-eyed and curious as well as imaginative, Emaleen is early to understand the truth of the strange man and to accept him just as he is.

ADVERTISEMENT

Ivey’s inspiration may have come from source stories, including those of beings that can transform between humans and animals, but “Black Woods, Blue Sky” is an original work of art that only Ivey’s inventive powers, deep knowledge of Alaska and its creatures, and commitment to depicting the real, loving, and often confused lives of her characters could create.

By Marybeth Holleman; University of Alaska Press, 2026; 294 pages; $95 Hardcover, $21.95 paper, $17.95 Ebook.

Marybeth Holleman, an Anchorage writer whose previous books include “The Heart of the Sound,” “Among Wolves,” and “tender gravity: poems,” has brought together her tremendous writing skills and her knowledge of places, science, environmental issues, art, and the human heart to create a compelling novel about the forces that entwine lives and events.

“Bloom Again” presents a realistic portrait of contemporary life with extreme weather, habitat loss, and characters who face their doubts and fears to learn, create, and find joy. Readers will be drawn to not only the two women central to the story — an artist from Alaska and a scientist from North Carolina — but the full cast of friends, family, colleagues, even animals and plants with key roles.

Science and art are at play throughout. As one character says, “Art can reach people in ways that science can’t. That it bypasses the analytical mind and goes straight to emotions and imagination, creating understanding and empathy.” This understanding lies at the center of this beautifully written story.

Nonfiction

Alaska’s extreme environments invite both actual adventurers and those who like to read their stories. This year three outstanding nonfiction works are set in very challenging places.

“Thirty Below: The Harrowing and Heroic Story of the First All-Women’s Ascent of Denali”

By Cassidy Randall; Abrams Press, 2025; 275 pages; $28.

In 1970, a team of six women (“the Denali Damsels”) climbed to the top of Denali — and, significantly, made it safely back down. This little-known expedition has finally been exceedingly well researched and told by author Cassidy Randall, who examined the lives of each woman as well as the climb itself.

A recurring theme throughout the book is the obstacles — in careers as well as climbing — that all the women encountered. For readers in 2025, it may be surprising — even shocking — to remember or learn the extent of discrimination that existed for women as recently as the 1960s. Women were not only barred from mountaineering clubs. They also faced roadblocks from entering medical and science programs and to finding jobs in those fields.

ADVERTISEMENT

Early chapters visit the backgrounds of all six women. The second half covers the expedition’s final preparations and then the climb itself, day by day. Armchair adventurers will get their money’s worth of learning what high-altitude, cold-temperature, avalanche-prone, and gale-force-wind conditions feel like and how they affect bodies, brains, and life-and-death dependencies. The high-drama of the descent makes for edge-of-the-seat reading.

“A Place Among Giants: 22 Seasons at Denali Basecamp”

By Lisa Roderick; Catharsis/Di Angelo Publications, 2024; 457 pages; $25.

The giants referenced in Roderick’s title, we learn, are Denali and the other mountains of the Alaska Range, but they might as well include the climbing guides, mountain rangers, glacier pilots, and rescuers who fill this absolutely absorbing memoir. “A Place Among Giants” chronicles the two-plus decades during which the author managed the basecamp on Denali’s Kahiltna Glacier, from which permitted climbers (over a thousand each year) mount their expeditions.

Roderick’s immersive writing takes readers right into the heart of life at the basecamp, including the logistics of daily life, the various personalities with whom she dealt, and the partying and pranks that helped define the community. She presents the pilots and rangers in memorable detail and does an equally exemplary job of describing the lives of alpinists and, always with understanding and personal anguish, some of the mountaineering and aviation tragedies that occurred during her time.

Beyond telling the story of a singular life in a remarkable place, “A Place Among Giants” asks readers to consider the values that shape a life and what it means to make choices that balance risk and safety, the needs of oneself and others, the ambitions of youth and the graces of maturity.

ADVERTISEMENT

“North to the Future: An Offline Adventure Through the Changing Wilds of Alaska”

By Ben Weissenbach; Grand Central Publishing, 2025; 301 pages; Hardcover $30. Ebook $14.99. Audiobook $27.99.

In 2018, Ben Weissenbach, an undergrad student from California, met Roman Dial, the renowned adventurer, mathematician, biologist, and APU professor, and accompanied him on a moose hunt. That led to two lengthy science expeditions through the Brooks Range with Dial, in 2019 and 2021. In addition to these, Weissenbach also spent considerable time with Kenji Yoshikawa, a reindeer-herding permafrost expert, and Matt Nolan, an independent glaciologist who studies Alaska’s Arctic glaciers. He refers to the three as part of “a small and hardy group … in a kind of scientific Wild West.”

Weissenbach presents the science he learned in all its complexity and surprises, as a process that asks questions and is constantly revised. The one accepted fact is that the north of Alaska has been warming much faster than most of the rest of the planet, resulting in significant changes to weather, plant growth, animal movements, the freeze-thaw cycle, and human lives. Weissenbach documents this through his direct experience in the Arctic along with reporting on the work of the scientists he accompanied and further research, including that related to earlier explorers and scientific studies.

In our age of alienation from genuine experience and the natural world, it’s refreshing to come upon a young person, open to being tested and fortunate in his encounters, who inspires by his example. Many dream of adventure; few actually seek it. Fewer still can turn experience into artful and informative storytelling.

Poetry

ADVERTISEMENT

By Shannon Gramse; Cirque Press, 2025; 123 pages; $15.

Shannon Gramse’s “Lost Last Poems” is no ordinary poetry book, and there is neither anything “lost” nor “last” about the poems. Instead, the book is based upon a clever and entertaining conceit. In “An Annotator’s Forward,” the “annotator” (S.G.) explains that the mysterious manuscript was found on a USB drive by a snowboarding student and that he examined it reluctantly one evening. Charmed by the poems, S.G. presents his find as a Wunderkammer, a catalogue of curiosities, a gift from an unknown poet.

The 59 alphabetized poems begin with “Approaching King Island” and end with “Zen Erratic” and are followed by 20 pages of scholarly annotations that attempt to explain references in the poems and historical or cultural material they may have been drawn from.

Gramse, who teaches writing at the University of Alaska Anchorage, has not only had obvious fun with his fictional project but proved himself, with this first book-length poetry collection, a poet of the first-rank. Many of the poems relate to Alaska and its exploration history, others to Vietnamese history and contemporary life. Their forms are narrative, lyrical, dramatic, and experimental, a rich mix. “Lost Last Poems” deserves to be found among the best of contemporary poetry.

By Tom Sexton; Loom Press, 2025; 87 pages; $20.

Tom Sexton’s last book, published posthumously, includes poems that illustrate two qualities that his work has long been admired for — his attention to detail, especially in nature, and his affinity with the ancient Chinese poets. In three sections, “Dark Cloud in Isabel Pass” applies a clear, empathetic eye to both the natural and human-shaped worlds Sexton, a longtime University of Alaska Anchorage professor and a former Alaska Poet Laureate, inhabited.

ADVERTISEMENT

The first and largest section here presents poems of Alaska and elsewhere in the North, while the third section takes readers to the East Coast, where Sexton and his wife lived seasonally in recent years. The short middle section looks to the other east, that of the Chinese poets. The poems throughout are nearly all personal, the poet speaking as himself about what he observes and thinks. They also showcase his gentle humor. Several contemplate aging. Even the seemingly simplest among them bear repeated readings and contemplation.

An introduction to the collection by Mike McCormick of Eagle River adds context to the work and to Sexton’s beginnings and long life.

David James’ favorites of 2025

As usual with my annual favorites list, one book always shines above all others, and the rest, both nonfiction and fiction, fall in no particular order.

“After the North Pole: A Story of Survival, Mythmaking, and Melting Ice”

By Erling Kagge; HarperOne, 2025; 368 pages; $32.

My absolute favorite book of the year barely touches on Alaska, instead heading much farther north and far deeper into the imagination. Norwegian author Erling Kagge’s “After the North Pole” meditates on humanity’s ancient and still ongoing fascination with the planet’s apex, the history of early misconceptions and uncovered realities regarding what lies there, its exploration and attainment, an account of his own long walk over the ice to reach it in 1990, and philosophical musings about what it all teaches us of human experience and meaning.

Kagge spans the millennia, telling of Greek astronomer Pytheas’ northern journey circa 325 BCE, 17th century cartographer Gerard Mercator’s fanciful and unfounded polar map, 500 years of Europeans voyaging into the Arctic, the race to set the first foot on the earth’s pinnacle (which involved no small amount of lying by the initial claimants), an all but overlooked 1962 Soviet submarine journey he argues to be the true first verifiable arrival, and the rapid sea ice melting that will one day make reaching the pole by foot all but impossible.

Kagge’s account of his own journey never overruns the historical narrative, instead offering brief glimpses of being on the ice that vividly illustrate what others saw before him. This is quite a book.

“Becoming Ken: One Black Man’s Journey from Ivy League to Prison and Back Again”

By Ken Miller; Thought Leaders Press, 2025; 286 pages; $24.

Ken Miller, founder and president of Anchorage fundraising and grant consulting company Denali FSP, offers a gripping account in “Becoming Ken” of a life that few could escape from intact.

Adopted at age five, he was brought to Anchorage where he excelled in school, graduating with an acceptance letter from Dartmouth. There his downward spiral began. As a Black student in an overwhelmingly affluent white culture, he sought acceptance by relentlessly partying, plunging into decades of drug abuse, crime, cocaine trafficking, homelessness, prison sentences, and more. That he found his way out of it and became a successful businessman and mentor to youth in crisis is, for lack of a better word, miraculous.

“The Fairbanks Four: Murder, Injustice, and the Birth of a Movement”

By Brian O’Donoghue; Sourcebooks, 2025; 350 pages; $27.99.

In October of 1997, 15-year-old Johnathan Hartman was beaten to death on a street in Fairbanks. With minimal investigation, four young men, three of them Native, were quickly arrested. Two offered confessions under interrogation, which studies have determined to be common for young suspects who are in fact innocent. A witness claimed to have clearly seen all four engaged in the beating despite watching from a significant distance on a dimly lit street while intoxicated. From this, all four men, who become known as the Fairbanks Four, were convicted.

Native groups rallied, proclaiming their innocence. Soon longtime local journalist and UAF professor Brian O’Donoghue and his students began examining the state’s case. 18 years later their work finally convinced the courts, and the state vacated the convictions.

O’Donoghue’s book, “The Fairbanks Four,” tells how they did it. It’s primarily focused on their tireless efforts, not on the experiences of the men themselves, a story that we desperately need to have told. But this book meticulously details why the disparate groups that rallied to their defense were more than right to do so.

“No Place Like Nome: The Bering Strait Seen Through Its Most Storied City”

By Michael Engelhard; Corax Books, 2025; 306 pages; $24.

Straddling mythology and urbanity, Nome is both a product of Alaska’s storied Gold Rush and a remote community holding fast to the far end of the continent. In “No Place Like Nome,” the always engaging Michael Engelhard, a former resident, walks both its streets and its setting.

Along with a lively and required telling of the town’s founding days, Engelhard details the natural history of the ecosystem it was built upon, explores the cultures and practices of the Indigenous residents who long preceded gold-thirsty European intruders, profiles some of the eccentric personalities who passed through the city, and illustrates it all with numerous historical photographs. Anecdotal and entertaining, it’s a guided tour by a man who knows the place well.

By Erica Watson; Porphyry Press, 2025; 192 pages; $20.95.

Erica Watson, a longtime resident of the Denali Park area, explodes preconceptions in her debut essay collection “Ghosts of Distant Trees.” She recounts her days as a seasonal employee at Alaska’s most popular national park, her gradual recognition that, contrary to popular belief, it can hardly be called a wilderness, and her settling into the nearby community, seeking balance between the lands she loves and the complicated lives of those who live on them.

Watson touches on many other subjects as well. Death, life, the urge to travel and the cost to the planet of every jet in the sky, climate change and her own complicity in it (and thus the complicity of all of us), the role of rocks and gravel in propping us up, and much more, all of it written with penetrating clarity, deep self-examination, and flashes of humor. She takes the award for best new Alaskan voice of 2025.

“Feeding Ghosts: A Graphic Memoir”

By Tessa Hulls; MCD/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2024; 400 pages; $40.

Juneau author and artist Tessa Hulls won a well-deserved Pulitzer this year for her memoir “Feeding Ghosts,” which delves into the wounds of history on one family’s journey through China and the United States, from pre-World War Two onward.

Tracing the experiences of her grandmother, mother, and herself, it’s a story of entrapment and escape. Hulls’ grandmother was born in the final years of China’s warlord era, endured the Japanese occupation of World War Two, and became a journalist and early critic of the People’s Liberation Army. She fled to Hong Kong with her daughter, Hulls’ mother, wrote a bestselling memoir, and descended into mental trauma she never recovered from.

The pair came to America, where Hulls was born and grew up torn between her American citizenship and Chinese heritage. Shifting across timelines and continents, she unravels all three lives, including her own, which she has spent seeking her identity by crisscrossing the country and traveling to China while her mother and grandmother wage their own battles with the emotional wounds they carry. It’s a much-needed examination of the immigrant experience in an unfortunate age of xenophobia.

[Alaska-based author and artist Tessa Hulls wins Pulitzer Prize for memoir ‘Feeding Ghosts’]

By Sarah Birdsall; Epicenter Press, 2025; 270 pages, 16.95.

Talkeetna author Sarah Birdsall continues to be Alaska’s noir virtuoso with “Hill of Dead Horses,” a story set in the southern foothills of the Alaska Range, and split between two eras.

The first is the late 1920s at a lodge built along the newly established railroad, where a mysterious young woman arrives to take a menial job. She’s a dead ringer for a girl that a local backwoodsman had once known and loved in Southeast Alaska.

Five decades later a couple from California settle in, seeking to heal their shattering relationship and free him from drug addiction by building a cabin on the land where the lodge once stood until burning to the ground.

Ghosts living and dead haunt this novel that slowly weaves two plots into one. Birdsall skillfully evokes landscapes and history while exposing the secrets humans keep even from those they are closest to, bringing it to a darkly atmospheric conclusion.

By Richard Chiappone; Alaska Literary Series/University of Alaska Press, 2024; 168 pages, $19.95.

Richard Chiappone has long wandered across Alaska’s literary landscape through essays, short stories, and, thus far, one novel. His writing delves into the truths of human nature and captures the lived experience of Alaskans, never falling into the stereotypical tropes that define who we are to so many people across the world.

“Uncommon Weather” collects vignettes set in locations rural and urban, from his hometown of Homer, to the Noatak River, to an off-the-grid cabin, to the streets of Anchorage. He presents the broad diversity of Alaska, and the commonality of individuals struggling with the places where they dwell and the choices they’ve made. Each story captures a few brief moments in their messy and unresolved lives before leaving them still there in the final paragraph. The inconclusive nature of these endings mirror the lives we all live.

By Naomi Klouda; Alaska Whale Press, 2024; 104 pages, $12.99.

Naomi Klouda’s charming young adult novel “Anna’s Whale” takes place in the fictional coastal village of Sunavik, where one day a whale washes ashore. Initially taken for dead, it’s subsequently discovered to be alive and carrying a calf. The villagers are unsure what to do with it, and soon government scientists arrive seeking their own solution.

The whale’s chief advocate is a plucky 12-year-old girl named Anna. Along with two young friends, she finds herself shuffling between village leaders and trained experts, negotiating between two cultures that are themselves pulled in differing directions from within. The heart of this story lies in how the children forge common ground between them. Klouda never creates a villain, nor does she favor one side over the other. Instead she uncovers the challenges and rewards of listening across divides as her characters resolve a problem none wants to end badly. It’s a lesson not only for children, but for all of us as we head into another year in an era when we need to do much more of that.