This post was originally published on here

A sacred book is paying a visit to Sacramento.

The Ireichō Book of Names is a monument representing the Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II. The book is the first comprehensive list of the more than 125,000 persons of Japanese ancestry incarcerated in U.S. government-run camps during the war.

The book is currently on a national tour, including stops at each of the 10 former camps for descendants of those incarcerated to leave a personal mark beneath the name of their loved one.

The California Museum is hosting the Sacramento stop, where the Ireichō Book of Names will be on display from Feb. 14-19.

One person deeply connected to the book is Sharon Fujimoto-Johnson, a Roseville-based children’s book author-illustrator and fourth-generation Japanese American. Her grandfather was imprisoned during WWII at an incarceration camp in Hawaii.

Fujimoto-Johnson never met her grandfather, but carries his legacy in the form of shells he collected while at the camp — shells which inspired her latest book.

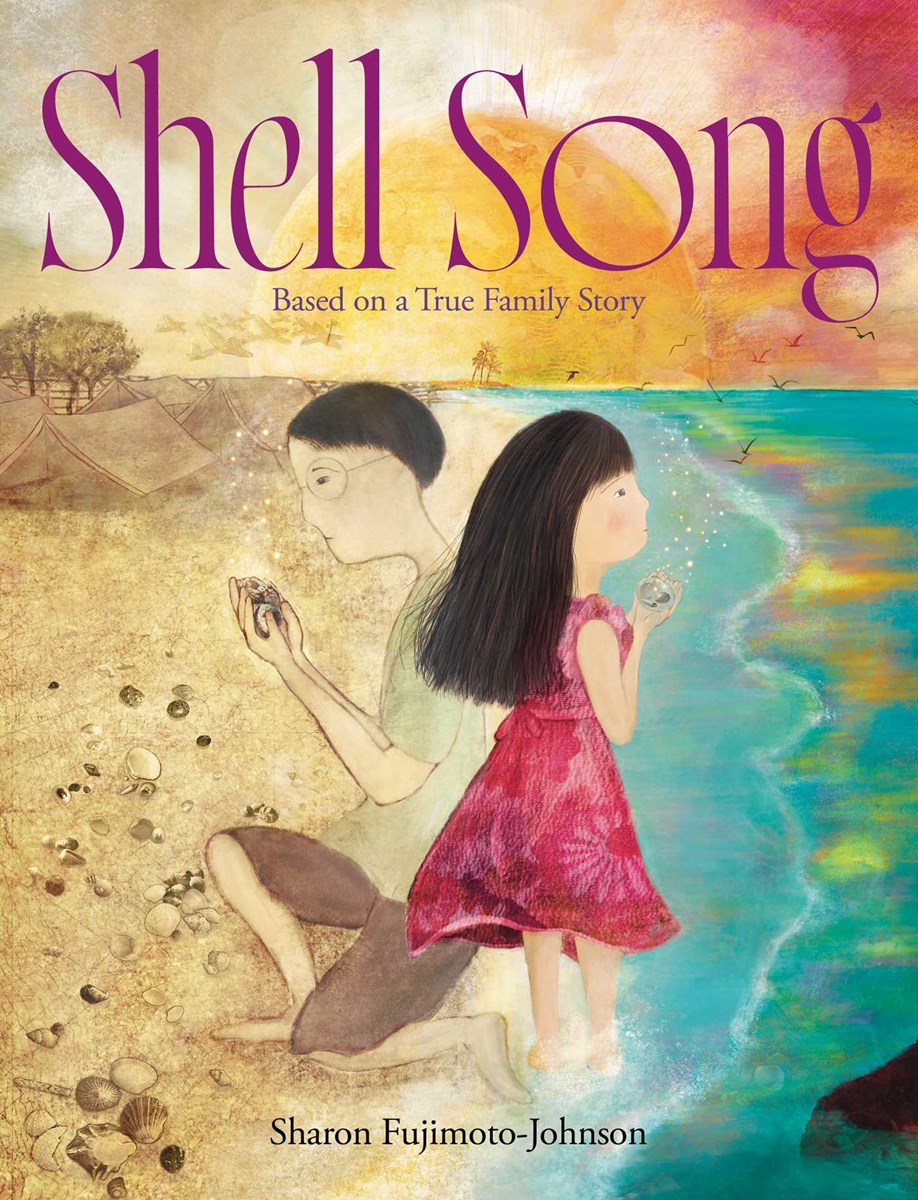

Fujimoto-Johnson joined Insight Host Vicki Gonzalez to talk about Shell Song, and how it draws inspiration from her grandfather’s story.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Interview highlights

Your family goes back four generations in the United States. Tell us about your family history.

My great grandfather immigrated from southwestern Japan to Hawaii in 1903. He was the first generation, he founded Fujimoto Trading Company on the big island in Hawaii. At that time most Japanese immigrants worked on the plantations or on the farms, but he went into business instead. His company ended up being the largest trading company between Hawaii and Japan

How did you begin learning about your grandfather?

Sharon Fujimoto-Johnson.Courtesy of Sharon Fujimoto-Johnson/Britt Honey Photography

Well, my grandmother was a storyteller. She was always telling us stories, and she also wrote her autobiography and a whole collection of poems in Japanese. When I was in college she actually entrusted that whole body of work to me, and I had the honor of translating all of her written work into English. Partly so that my family members who don’t read Japanese could access it, and also because I — even at that point — wanted the family story to go out to a wider audience.

You never met your grandfather. What can you tell us about what happened to him during his time being incarcerated at that camp in Hawaii, and also after the war?

Well, my grandfather, Shigeki Fujimoto, was actually a U.S. citizen by birth. So when Pearl Harbor was attacked by the Japanese military, many Japanese Americans in Hawaii were targeted. It was a little different from how it looked on the West Coast, where Executive Order 9066 allowed for the entire Japanese American community to be removed.

In Hawaii — which was not a state yet, it was a territory — martial law was used instead. Community leaders like teachers, priests and business leaders were selectively arrested and incarcerated. The actual target was my great grandfather, the founder of Fujimoto Trading Company. He had gone back to Japan on business and in war, the transportation between Hawaii and Japan was shut down. So he was unable to come back. So really it was in his place that my grandfather was arrested.

I happen to have in my possession his citizenship card verifying that he was a U.S. citizen, and also from the National Archives the paperwork that was used to process his incarceration. That paperwork is titled “Prisoner of War/Enemy Alien,” and he was obviously neither of those. He was a U.S. citizen by birth.

He only lived until his late 40s, correct?

Yes, that’s correct. Conditions in the camps were extremely harsh, especially in the beginning. There were threats of being shot. There were strip searches on a daily basis. Hard labor, lack of good food and really, perhaps the most damaging, isolation from family. And in my grandfather’s case, he was a young husband and father at the time. My grandparents had two young kids, ages two and one, and my grandmother was pregnant with their third child… who was actually my father.

She gave birth after my grandfather had been taken away from the family, and so my father met his father for the first time at Honouliuli Incarceration Camp when he was about four and a half months old. In her autobiography my grandmother writes about that moment, traveling these red dirt roads on a bus with the three young kids in tow, and how her husband was so thin and lonely behind barbed wire.

I actually had the chance last year to visit that actual site of the incarceration camp. It’s a national park now, Honouliuli National Historic Site. And last year they were commemorating the 10th year of this site being declared a national park. As a descendant I was invited to go on a tour to see the place where my grandfather had been incarcerated, because they’re talking now about the planning of this park, and what it’s going to look like in years to come. My 11-year-old daughter went with me on this trip, and so we were the first in my family to return to this place… and it looked exactly like my grandmother had described.

This incarceration camp was in a deep gulch between two mountain ranges. From the top of the mountain you can actually see Pearl Harbor in the distance, and then you descend down into this deep, deep gulch and when you look up, you can only see mountain and sky. It was extremely isolated, hot during the summers, cold at night. That’s where my grandfather spent his incarceration as well as a second location, Sand Island, also on Oahu.

The cover art of “Shell Song,” a new children’s book from Sharon Fujimoto-Johnson, a Roseville-based author-illustrator.Courtesy of Beach Lane Books/Simon & Schuster

The cover art of “Shell Song,” a new children’s book from Sharon Fujimoto-Johnson, a Roseville-based author-illustrator.Courtesy of Beach Lane Books/Simon & Schuster

What you are describing is such hardship. Why decide to make this into a children’s book?

I really believe children deserve access to all kinds of books. They deserve to see books that portray characters that look like themselves, but equally characters that don’t look anything like themselves or are living very different kinds of lives. I think that’s really how empathy starts, when we begin to understand that there are all kinds of storylines in life. Really each of our lives is a story, all of our lives are interconnected.

I wanted to write this book very honestly, but also simply enough and gently enough that even a young child could understand the core themes. It’s about family, hardship, loneliness and fairness.

You are also the illustrator of this book and it is just beautiful. What was the creative process like?

When I was about 10 or 11, I inherited my grandfather’s shell collection. Those shells traveled with me through the years. At some point I realized, it’s actually the shells that are the key to telling my grandfather’s story.

The actual shells are digitally collaged into the artwork, as well as soil from the two incarceration camp sites that he was in and that’s thanks to the Japanese American National Museum. They loaned me the soil samples to be photographed.

In the home scenes, I used my grandmother’s wedding kimono to create the wallpaper to sort of represent the warmth and security of home that she represented for my grandfather. And also in many of the scenes, the clothing that my grandfather in the book is wearing… I use textures and fabrics from my elderly father’s wardrobe. Essentially my grandfather is wearing the clothing of his now-elderly youngest son, who outlived him by many years.

The Ireichō Book of Names is coming to the California Museum this weekend. You will be going there and making that personal mark. How significant is this for you and your family?

This book represents so many names, and each of those names is a story. My grandfather’s name is in that book and his is only one of the many, but I’m so grateful that next week I have the chance to take my 83-year-old father to stamp next to his father’s name in that book.

What do you think that will mean to him?

I think it will be very emotional for all of us, and really it’s a way of continuing my grandfather’s story for this generation and for the next. To continue the idea that his story really mattered, and continues to matter.

CapRadio provides a trusted source of news because of you. As a nonprofit organization, donations from people like you sustain the journalism that allows us to discover stories that are important to our audience. If you believe in what we do and support our mission, please donate today.