This post was originally published on here

Sci-fi is typically associated with gadgets, special effects, and far-flung futures, but there’s a lot more to the genre than that. At its best, it can be a philosophical instrument, a psychological mirror, or a structural experiment. The finest sci-fi stories use an imagined tomorrow to comment on today.

With this in mind, this list looks at some more unorthodox sci-fi movies that challenged the genre’s conventions and broadened its possibilities. They use their speculative elements as a vehicle to explore rich themes and complex characters, resulting in triumphs that have redefined sci-fi for the silver screen.

‘Alphaville’ (1965)

“Sometimes reality is too complex. Stories give it form.” Alphaville is a tech noir by Jean-Luc Godard. That already lets you know you’re in for something unique. It presents a futuristic city governed by a sentient computer that has outlawed emotion, poetry, and irrational thought. Into this cold, technocratic world arrives a hard-boiled secret agent (Eddie Constantine) tasked with dismantling the system from within. From here, the plot filters detective tropes through philosophical inquiry, all trench coats and existential musings.

The central conflict is thematic and psychological: the tension between cold technological rationality and messy human feeling. In terms of aesthetics, Alphaville totally demolishes the idea that science fiction requires elaborate sets, distant planets, or flashy special effects. It mostly just uses real contemporary Paris locations, deprived of ornamentation. By stripping the genre down to its core, Godard reminds us that it can be a potent tool to comment on the present.

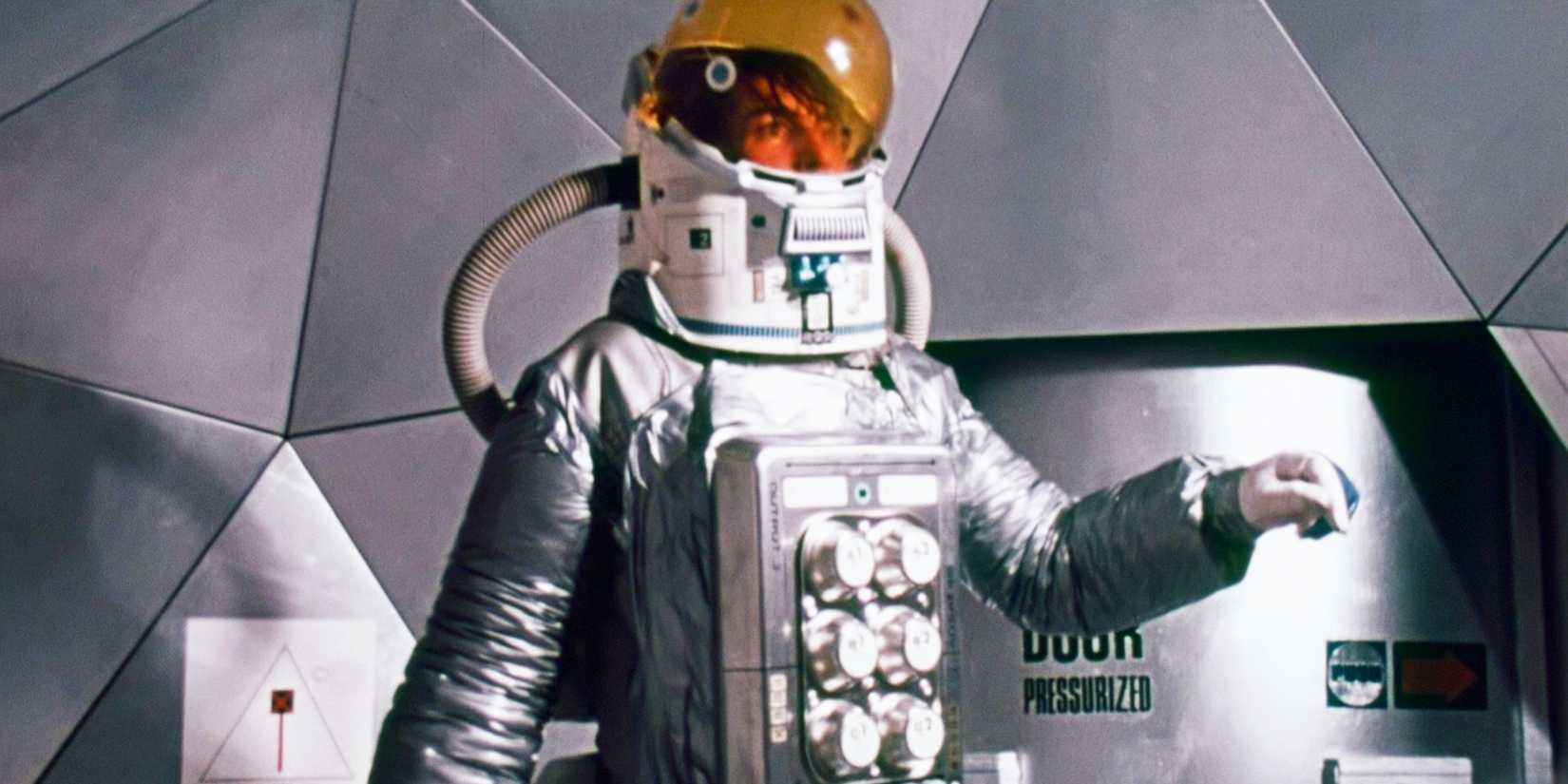

‘Dark Star’ (1974)

“Let there be light.” Dark Star is the lean, low-budget feature debut from John Carpenter, co-written by Alien‘s Dan O’Bannon. Rather than being polished and slick, it is a lived-in, grimy sci-fi that follows a crew of astronauts drifting through deep space on a long-term mission to destroy unstable planets. Their days are filled with malfunctioning equipment, philosophical debates with sentient bombs, and crushing boredom. The plot barely advances, instead looping through routines, breakdowns, and absurd crises.

On the surface, it might just look like a wacky comedy, but its stronger effect is quietly destabilizing. Space is not a frontier of wonder here, but a workplace defined by drudgery: monotonous, alienating, and spiritually draining. Fundamentally, Dark Star suggests that even in the vastness of space, human pettiness and absurdity persist. In this regard, the movie was a major break with the sci-fi conventions of its time.

‘Gattaca’ (1997)

“There is no gene for the human spirit.” Gattaca imagines a near future where genetic engineering determines social hierarchy. Those conceived naturally are relegated to menial labor, while genetically optimized individuals dominate prestigious careers. In this stratified world, Ethan Hawke plays Vincent Freeman, a man born with perceived genetic “defects” who assumes another identity to pursue his dream of space travel. His story is both a character study and a thriller as he strives to avoid detection: every hair, drop of blood, and fingerprint becomes a threat.

The movie is great because it’s all eerily plausible. The minimalist aesthetic and restrained performances ground the more speculative elements. Plus, many of the ideas it engages with are becoming more real by the day: already, ethical debates are raging about gene editing and designer babies. Some people warn that we’re heading to a future where inequality extends down to the cellular level, with wealthy elites buying even genetic advantages.

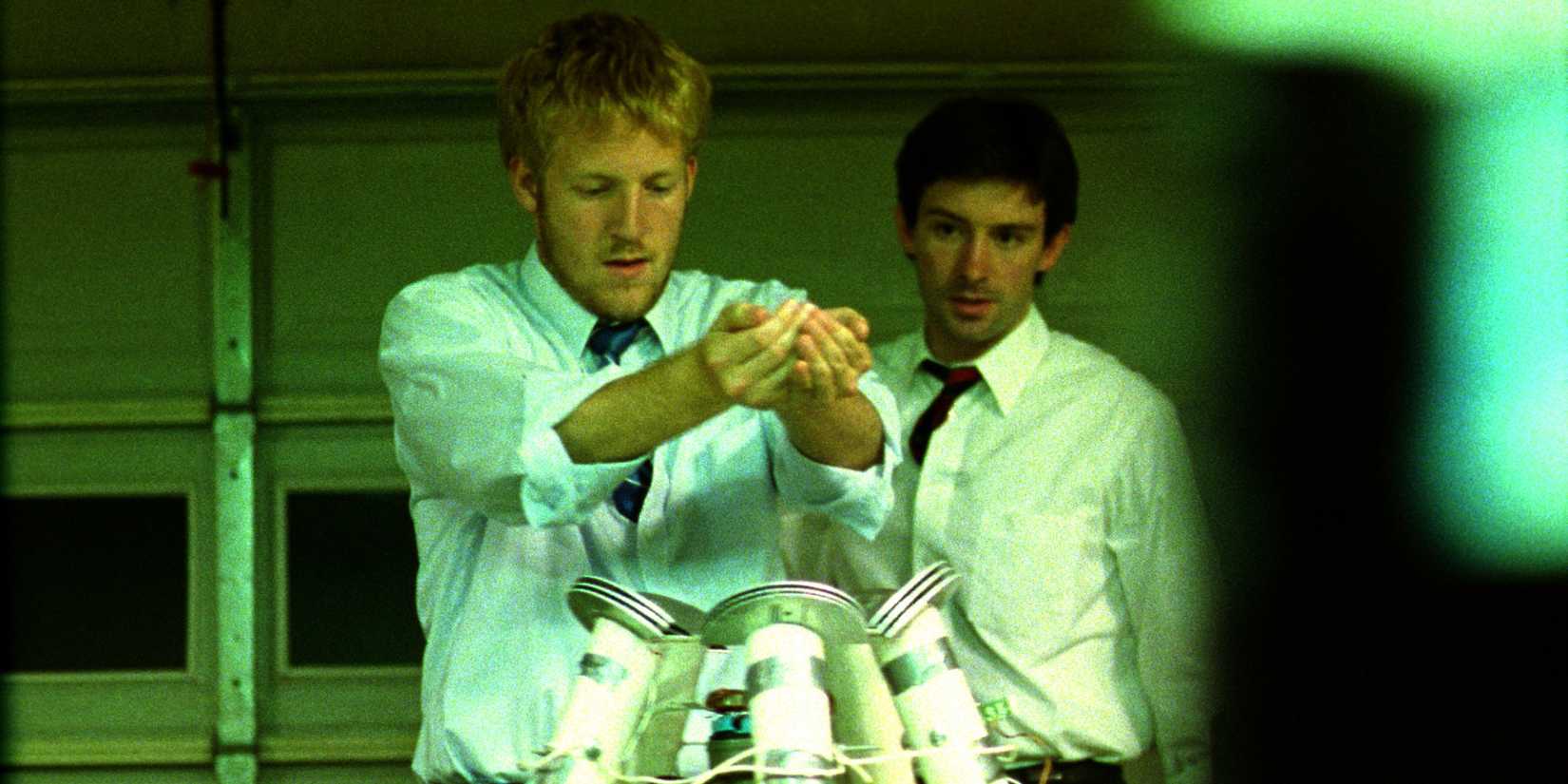

‘Primer’ (2004)

“I haven’t really told anyone this.” Primer is one of the very best time travel movies ever made, built almost entirely on incredibly careful plotting. It’s about two engineers (played by David Sullivan and Shane Carruth, who also writes and directs) who accidentally invent a form of time travel while working on a side project. Rather than being a grand adventure, the movie treats time travel as an engineering problem, complete with diagrams, overlapping timelines, and mounting paranoia. It’s very much a film of ideas rather than action.

The plot quickly becomes recursive and opaque. Conversations reference events the audience hasn’t seen yet, and cause-and-effect collapses under repeated temporal interference. It all means that Primer can be confusing on first watch, but it lends itself to repeated viewings and grows more satisfying the more you understand its subtleties. It’s truly impressive what Carruth achieves here on a budget of just $7,000.

‘Solaris’ (1972)

“We don’t want other worlds. We want mirrors.” Solaris is one of the defining achievements of Soviet filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky. It centers on a psychologist (Donatas Banionis) sent to a space station orbiting a mysterious planet capable of manifesting human memories. Upon arrival, he discovers the crew psychologically unraveling as physical incarnations of their guilt and longing appear aboard the station. Eventually, he, too, begins seeing impossible things, including a replica of his dead wife (Natalya Bondarchuk).

Through it all, the planet remains unknowable, resisting explanation or conquest. Tarkovsky turns this setup into a sweeping meditation on the boundaries of reason and the strange, destructive pull of doomed love. It’s an emotional sci-fi rather than a technical one. In the end, Solaris reminds us of how fragile our sense of reality can be, and how forcefully the unconscious mind shapes us. The American remake is solid, but those curious about this story should seek out the original.

‘Dark City’ (1998)

“You still don’t understand what you’re dealing with, do you?” Dark City is a sci-fi neo-noir from the mind of Alex Proyas, director of The Crow. The main character is John Murdoch (Rufus Sewell), a man who wakes up in a bathtub with no memory of who he is, only to discover that the city around him is manipulated nightly by shadowy figures known as the Strangers. As midnight arrives, time stops, buildings rearrange themselves, and identities are reassigned, turning the city into a living laboratory.

There are some parallels to Alphaville in that this movie is also a noir mystery wrapped inside metaphysical sci-fi. As the protagonist pieces together his past, he begins to suspect that memory itself is the mechanism of control. Themes aside, Dark City is simply atmospheric and visually striking, like a living Edward Hopper painting. Though it flopped on release, the film has now rightly become a cult favorite.

‘Stalker’ (1979)

“Happiness is a very serious thing.” Tarkovsky strikes again. Stalker follows three men — a guide (Alexander Kaidanovsky), a writer (Anatoly Solonitsyn), and a scientist (Nikolai Grinko) — as they journey into a forbidden area known as the Zone, a place rumored to grant a person’s deepest desire. The plot is deceptively simple: a trek across desolate terrain toward a room that promises fulfillment. But what unfolds is not an adventure, but a spiritual trial. Rather than a journey to the outer limits, we get a journey inward.

The Zone resists logic, punishing certainty and rewarding humility. Each character is forced to confront the gap between what they say they want and what they actually desire. Tarkovsky provides ample space and time to delve deep into their psychology. The visuals reflect this patience, too: the camera moves are subtle, and the takes are long, with the average shot lasting over a minute.

‘Coherence’ (2013)

“I don’t think this is our house anymore.” Coherence is another low-budget sci-fi that proves that a good script is more important than elaborate special effects. It begins with an intimate dinner party among friends on the night a comet passes overhead. Soon, reality itself fractures, and the group discovers that multiple versions of themselves may be occupying parallel worlds, each one diverging in small but devastating ways. The characters begin to question not just where they are, but who they are relative to alternate selves who may have made slightly better or worse choices.

The tension comes from the protagonists trying to figure out the situation and, indeed, make it back to their reality alive. It’s enjoyable watching them come up with ingenious ways of outsmarting their other selves. It all builds up to a delectably dark ending that’s the perfect payoff for everything that’s come before.

‘Her’ (2013)

“The heart is not like a box that gets filled up.” Spike Jonze‘s Her was already great on release, but time has revealed it to be one of the most perceptive and prophetic sci-fi movies of the 2010s. Joaquin Phoenix leads the cast as a lonely man who begins a relationship with an advanced operating system (voiced by Scarlett Johansson) designed to adapt, learn, and emotionally engage with its user. Through these characters and their bond, the film explores intimacy, dependency, and the limits of human connection in a technologically mediated world.

In other words, the dynamic between the protagonist and his machine is worlds apart from Bowman and HAL 9000, and a lot closer to the reality we’re rapidly moving toward. The idea of a person developing a close relationship (indeed, falling in love) with an AI companion is no longer far-fetched at all. As AI technology continues to advance, and as people grow more isolated and lonely, Her‘s message is only going to resonate more deeply.

‘Paprika’ (2006)

“Reality is inside the mind.” Many people may know Paprika as one of the movies that inspired Inception, but there’s a lot more to this animated masterpiece than that. Story-wise, it focuses on a team of scientists who develop a device allowing therapists to enter patients’ dreams. When the technology is stolen, dreams begin to spill into waking life, collapsing boundaries between fantasy, memory, and reality itself. From here, the plot accelerates into controlled chaos, with identities dissolving and visual logic giving way to associative imagery.

While the themes are rich, the most lasting impact of this Satoshi Kon masterpiece was aesthetic. It hugely innovated in terms of how sci-fi can be visualized. The movie treats consciousness as fluid, playful, and dangerous, using animation to express ideas impossible in live-action form (well, unless you’re Christopher Nolan). Scenes melt into one another; identities blur; reality becomes porous in a visual stream of consciousness.

Paprika

- Release Date

-

October 1, 2006

- Cast

-

Megumi Hayashibara, Tohru Emori, Katsunosuke Hori, Toru Furuya, Akio Otsuka, Koichi Yamadera, Hideyuki Tanaka, Satoshi Kon, Yasutaka Tsutsui, Satomi Korogi, Rikako Aikawa, Mitsuo Iwata, Shinya Fukumatsu, Eiji Miyashita, Shinichiro Ohta, Akiko Kawase, Anri Katsu, Kozo Mito, Katsunori Kobayashi, Seiko Ueda, Daisuke Sakaguchi

- Runtime

-

90 minutes

- Director

-

Satoshi Kon

- Writers

-

Seishi Minakami, Satoshi Kon