This post was originally published on here

By: Majid Maqbool

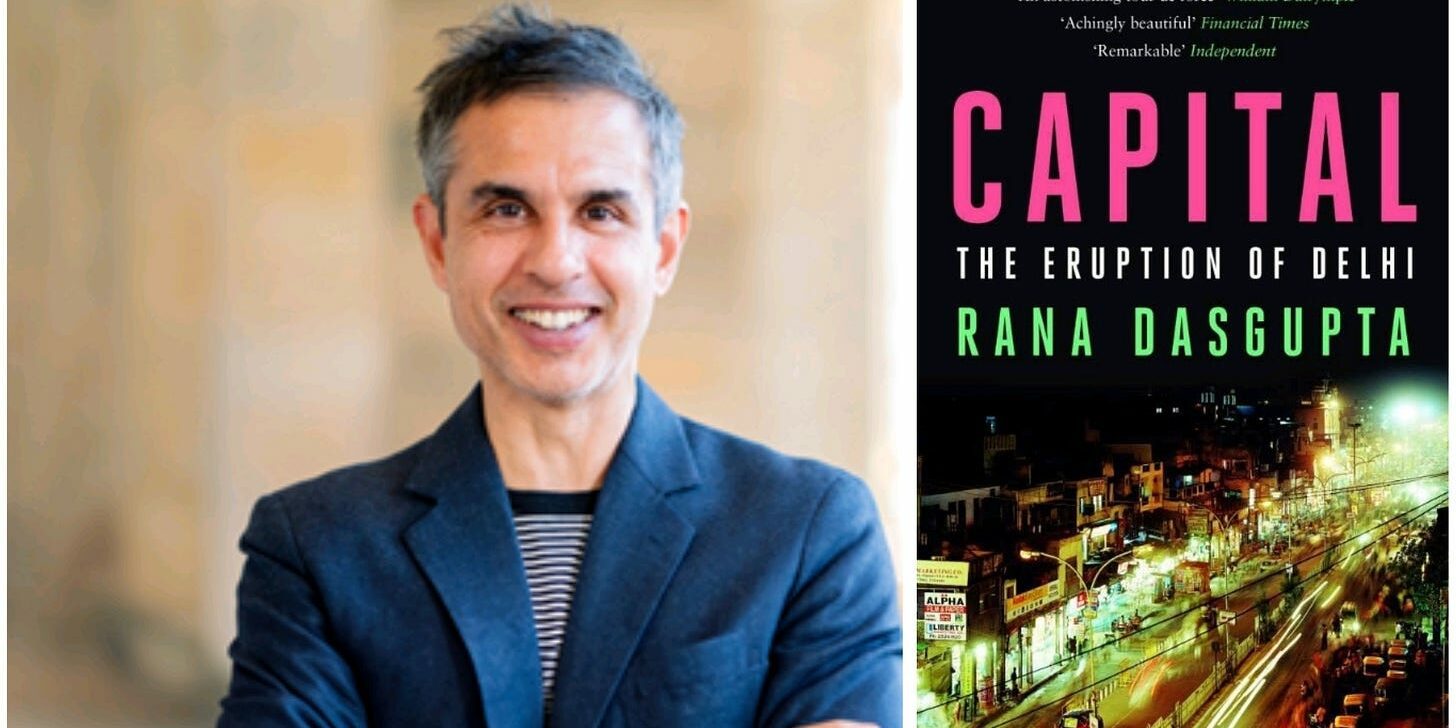

British-Indian novelist and essayist Rana Dasgupta studied philosophy at Balliol College, Oxford, and earned a PhD at the University of Wisconsin-Madison before turning to writing. His debut collection, Tokyo Cancelled—a set of interconnected stories inspired by modern folktales—was published in 2005. This was followed by his novel Solo (2009), which chronicles a Bulgarian centenarian’s reflections on 20th-century upheavals and futuristic visions. The novel won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize.

His 2014 nonfiction book on the impact of globalization on his adopted home city, Capital: The Eruption of Delhi, received the Ryszard Kapuściński Award, was shortlisted for the Orwell Prize, and nominated for the Ondaatje Prize.

Dasgupta’s most recent book, After Nations: The Making and Unmaking of a World Order (Allen Lane/Penguin, 2025), traces the evolution of the nation-state system—from ancient empires to today’s tech-driven crises. It “critiques failures in addressing migration, ecology, and inequality, urging a post-national reimagining of citizenship, law, and economy.”

In an interview with Majid Maqbool for Asia Sentinel, Dasgupta—whose writings explore themes of migration, inequality, and global systems across genres—discusses growing up between two cultures that have shaped his writing and reading life, and how thinkers and writers like Marx, James C. Scott, and Thomas Piketty have influenced his intellectual and literary outlook while critiquing imperialism, capitalism, and global power structures.

Edited Excerpts:

You grew up between two cultures in England, with Indian roots shaping your sense of the world. What kinds of books did you read as a child and adolescent, and how did those early reading experiences influence the writer—and reader—you later became?

Yes, my two cultures affected my outlook significantly. I was a British kid who didn’t fit entirely into the British story, but who certainly didn’t fit into the Indian story either. So I’ve always had some dissatisfaction with the grand stories nations tell about themselves. As an adolescent, I was particularly drawn to stories of outsiders – including Camus’s The Outsider. I loved Dostoevsky.

What are some works of nonfiction that have profoundly shaped your intellectual and literary outlook, particularly influencing your critiques of imperialism, capitalism, and global power structures?

I reached adulthood in the aftermath of Soviet collapse – during the triumph of Western liberalism and capitalism. But that era was very unconvincing. It was supposed to bring peace and freedom, but the opposite was true. I tried to understand why systems built on apparently peaceful principles could never in fact be peaceful. Marx, of course, was a touchstone. But also more recent thinkers such as James C Scott, who had a clearer understanding of state power, colonialism and ecology, and Thomas Piketty, who documented the decline of Western equality.

Your recent book ‘After Nations’ examines how the empire continues to economically and politically rewire Asia. During the research and writing of this book, which texts were most central in helping you develop and sharpen its arguments?

A major theme is international law: how international law has worked to perpetuate the power relations instituted during the period of European empire, and to stop nations from rising or falling in the economic hierarchy. A few books were essential in this: Antony Anghie’s Imperialism, Sovereignty and the Making of International Law (Cambridge University Press, 2005), Katerina Pistor’s The Code of Capital (Princeton University Press, 2019), and Branko Milanović’s Global Inequality (Harvard University Press, 2016).

I feel the implications of Chinese power are also poorly understood, partly because our conversations are very short term. With his book, The Great Divergence, Kenneth Pomeranz began a very important conversation which has been taken up by such other fascinating writers as Peer Vries and Roy Bin Wong.

For readers engaging with your latest book, ‘After Nations’, are there other books or texts you would recommend as parallel or companion readings that can deepen understanding of the issues you explore in the book?

I feel strongly that we are victims, today, of the fact that our picture of the world is very artificial. We are bewildered by the world because our stories of it are fossilized, and have little to do with the world as it actually is. Some books which can correct this: Ntina Tzouvala’s Capitalism as Civilisation; David Graeber & David Wengrow’s, The Dawn of Everything.

In your nonfiction, especially in Capital, you’ve written powerfully about urban transformation and the lived experience of cities like Delhi. Any books or texts you found especially illuminating on cities, urban change, and modernity you’ve also explored in this book?

Mike Davis’ astonishing book, Victorian Holocausts, offered a perspective I wished I’d known about when I wrote Capital. It would have expanded my sense of the traumatic history of colonial urbanism. But after writing three books about cities, I think After Nations has increased my appreciation of the global countryside. One of the most serious charges against the modern nation-state system is that it has destroyed, not only our natural heritage, but also agrarian systems and cultures. Peasants, the upcoming book by my partner, Maryam Aslany, offers a crucial corrective to the urban bias which shapes almost all consideration of “modernity”.

Is there a lesser-known or under-read book that you feel captures the current moment of xenophobia, fragmentation, and global disorder particularly well?

I see the nation-state system as a mechanism for transferring resources from poor regions to rich ones, and for exporting war, poverty and ecological destruction in the opposite direction. In order really to understand what our world is about, it’s essential to look at Africa, which bears by far the deepest scars of this process. Read the Congolese novelist Jean Bofane, for instance.

Is there a recently published novel or work of nonfiction that you’ve found exceptional—one you would highly recommend for both its literary merit and the clarity of its insights?

Lyn Alden’s Broken Money. In much of the world, the inability of states to supply currencies in which populations may reliably store value and transact is another major problem of our present system. She offers a provocative but fascinating account. The ever-brilliant Lea Ypi has just come out with another book, a family memoir tracing the development of Balkan states out of the Ottoman empire – more wonderful insights into the making of our “world order”.

As a writer who reads across cultures and disciplines, what kind of reading do you find yourself drawn to of late, and how does it influence the direction of your future writing?

Like many people, I’m currently finding the world as it is very wearying. Partly in preparation for my upcoming novel, and partly because it is a relief to retreat to beauty and grandeur. I’m reading a lot of Jewish philosophy at the moment. Writers on Jewish mysticism of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It’s a new world to me, and thrilling.