This post was originally published on here

I have a problem. It embarrasses me, professionally, to admit it—but here goes: these days, I can’t seem to finish a book.

That’s an exaggeration, of course. Some books I do finish. When I read to my daughters, we almost always make it to the end. Stopping out of boredom or disappointment would be freakish and rare. And if I’m reviewing a philosophical text or teaching a book to my students, I finish. Professional duty still compels.

But when it comes to reading for pleasure—which I do a lot of—finishing has become the exception rather than the rule. I live among fragments. Seven or eight books teeter on my nightstand at any given time. I’m more than halfway through Naomi Klein’s Doppelganger, some way into Lea Ypi’s Indignity, partway through Everyone Who Is Gone Is Here by Jonathan Blitzer. At the same time, I’m rereading John Williams’s campus novel Stoner and James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son.

Only a few years ago, it was just the reverse. Finishing was the rule and stopping the exception. I look back now with pained nostalgia on that prelapsarian age. I had no idea how good things were.

The problem is not just that I’m raising three kids, working full-time and bone-tired in a way that feels structural rather than temporary. The problem is that I have come to read the same way I use the internet: with a million tabs open, terrified of missing something good, or of closing an interesting window too soon.

More than a century ago, the German sociologist Georg Simmel argued that modern urban life overwhelms us with stimuli—too many impressions arriving too quickly. To survive, the psyche becomes defensive. We skim. We detach. We flatten our responses. This is not laziness or moral failure; it is adaptation. Depth becomes costly—dangerous, even—when everything demands attention all at once.

Our digital lives have, of course, only intensified this problem. Online, meaning arrives in rapid bursts. The moment boredom threatens, something else appears: a headline, an outrage, a joke, a warning. The abundance is staggering, and social media propels us through it at breakneck speed, cultivating anxious, insatiable habits of attention along the way. There is always more to see, more to react to, more to keep up with. The present swells with choppy, unending urgency. Meanwhile, the past fades and the future presses in.

Hartmut Rosa, a contemporary German sociologist, calls this condition acceleration. The problem, he argues, is not simply distraction or a lack of discipline, but the erosion of stable relations to the world. When meaning itself becomes provisional—interruptible, replaceable, always on the verge of being outdated—nothing can hold us long enough to matter deeply.

And so we move restlessly from one thing to the next. Paradoxically, in trying to catch everything we miss what matters most: an entire quality of experience, a depth of being that shallow attention flatly rules out.

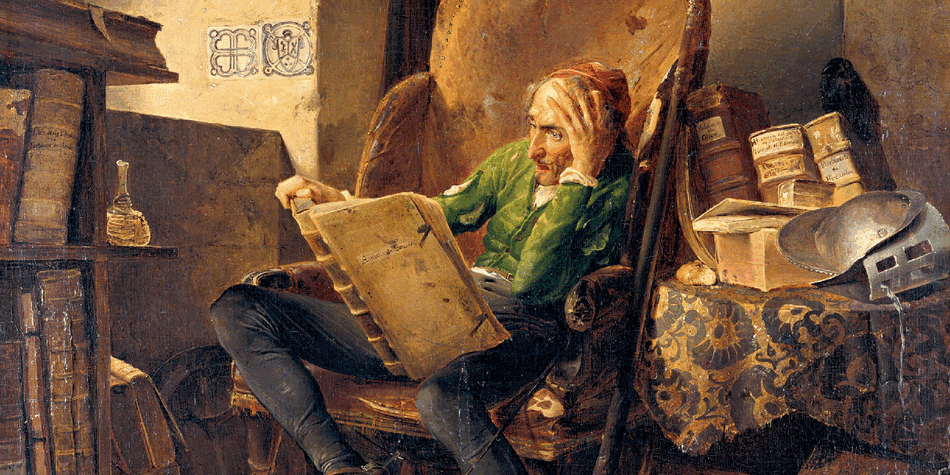

Reading a book asks something radically different of us. It requires trust. You don’t know where you’re going, or even whether the journey will be worth your time. You don’t know what the “point” will be, if indeed good literature has a point. You commit anyway. You allow yourself to be led through another person’s consciousness towards a destination that remains indistinct. Only patience and faith make this possible.

This is not an efficient use of attention, just the opposite. There is no dopamine hit, no hot take, no quick sense of having got what you came for. On the internet, the whole point is to move on. With good books, the point—if there is one—is to stay.

That staying matters. It’s how literature works its slow magic, showing you what the world looks like from someone else’s perspective. Empathy is a fashionable word, but genuinely inhabiting another consciousness is nothing short of a miracle, a genuine adventure. Reading a good book invites exactly that. It is fundamentally at odds with a culture that celebrates speed, productivity and optimisation.

I think longingly about how I used to read, especially as an undergraduate, before the internet. I relished War and Peace with the brash confidence of someone who believes time is endless; I spent happy weeks inside the world of Middlemarch, as though there were nowhere better to be.

Lately, I suspect I could only find my way back to this kind of reading by doing something radical. Not a new app. Not a changed setting. But a rupture. Leave the internet, perhaps. Move off grid. Abandon most of the trappings of modern life, with its fearsome technological tide that pulls us forever into the shallows.

I am not optimistic about my chances.

There is, of course, no shortage of books that diagnose this very problem. Many offer solutions. They counsel slowness, presence, the art of doing nothing. They preach the gospel of digital minimalism. I own several of these titles. They gaze at me from the stack that teeters, half-read, on my nightstand. Problem is, I’ll never finish them.