This post was originally published on here

Jewell Parker Rhodes didn’t set out to write books for young people.

Rhodes, a faculty member in Arizona State University’s College of Integrative Sciences and Arts, had written adult novels for 30 years until the morning after Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005.

Rhodes woke up hearing a child’s voice in her head. That led her to writing the children’s novel “Ninth Ward,” which featured a 12-year-old girl named Lanesha, who lives in New Orleans with her elderly caretaker.

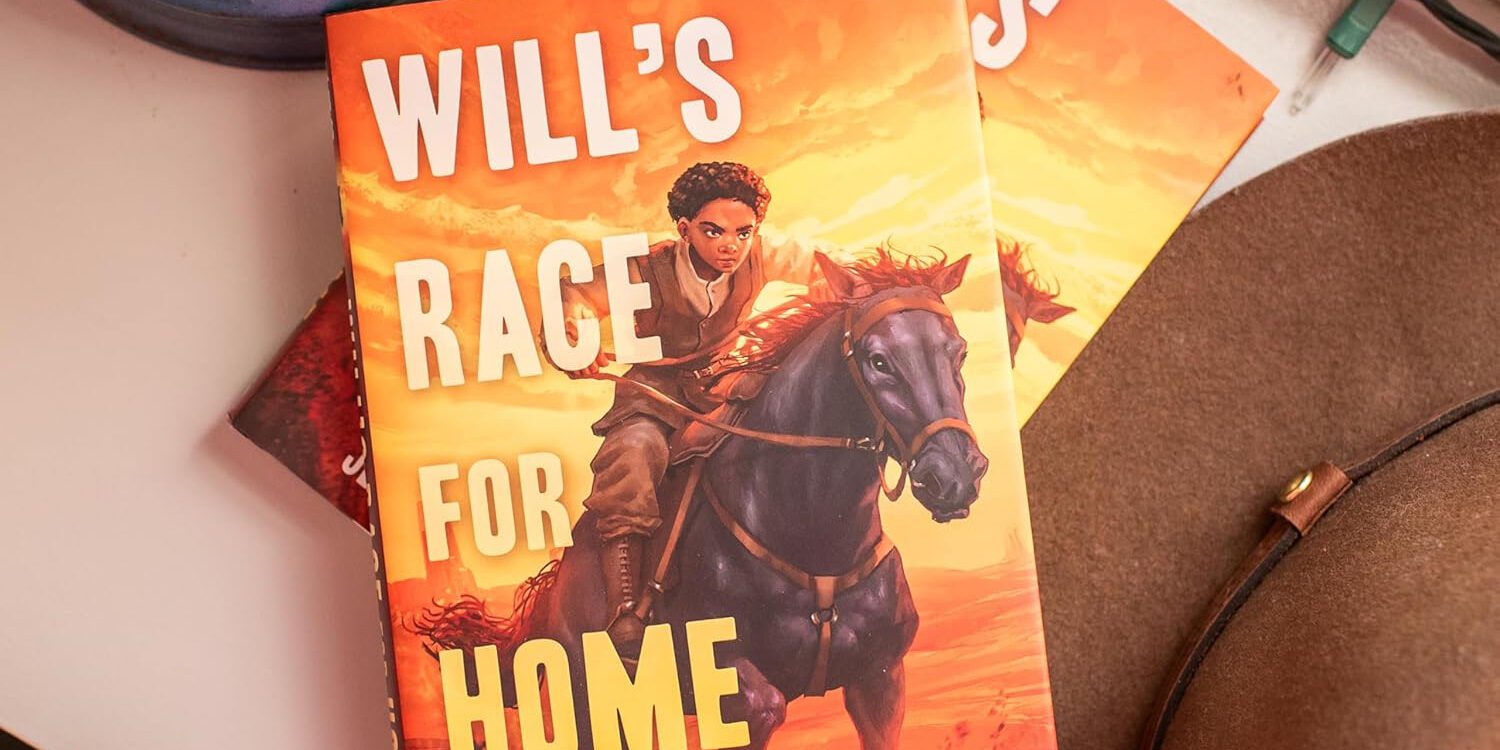

That led to a series of children’s books, including “Towers Falling,” about a fifth grader who lives in a New York homeless shelter 15 years after the attacks on 9/11. And her latest book, “Will’s Race for Home,” is about a Black father and his 12-year-old son, Will, as they set out to win land in the Oklahoma land rush.

Rhodes, who is also the Piper Endowed Chair of the Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing, has won a 2026 Coretta Scott King Book Award for “Will’s Race for Home” from the American Library Association.

Here, she talks about the book, the award and her life’s work.

Note: The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Question: Let’s start here: Why are you now a children’s book author?

Answer: I love young people and their sense of fairness. They inspire me and I love their curiosity. But I actually think the more I’ve been writing for children, the more I feel that they are really much more resilient and much more capable and intelligent than us adults want to give them credit for.

Through COVID, I couldn’t have kept going if I didn’t feel this connection with youth. Because it’s not my world. It’s going to be theirs. And I have such faith in them.

Q: What about the Oklahoma land rush made you write “Will’s Race for Home?”

A: When I was writing for adults exclusively, my second novel was about the Tulsa Race Massacre. So I used to wonder how the heck Black people got to Oklahoma. The last few years, I was reading and studying some more and found out about the land rushers. I always thought the land rushers were all white, because that’s all I ever saw. In fact, there was even an international component. But a lot of African Americans participated as well, and there were over a dozen Black towns that were started.

One of those Black towns was Deep Greenwood, which was bombed from the air during the massacre. So I was struck in terms of the history of how the land rushers probably would have been just 25 years past the Emancipation Proclamation. They had the courage, the resilience, the fortitude to make this demanding land rush, and then about 25 years later, one of those Black towns would be bombed from the air.

Also, I’ve been watching “Yellowstone” with Kevin Costner on television, and I also saw the Black production of Bass Reeves, the Black lawman (Reeves was a deputy U.S. Marshall in the late 1800s.) It reminded me of when I was a kid, and I loved those stories. So I wanted to write a Western.

Q: Your children’s books deal with topics such as racism and violence. How do you write about those things in a way that will appeal and be important to, say, middle-school children?

A: It’s interesting. After writing about Katrina and 9/11, apparently (my editors) saw that one of the things that my books did was to take hard subjects and write them in terms of context and theme and symbolism as if I were writing for adults. Also, because I’m a teacher and librarians are so wonderful, I’m also writing for them so that they have a book that they can help unpack for readers. A lot of my books are in the classroom, and that’s where I think they should be. Or read along with parents.

Q: Where did your love of writing — and that sense of perseverance in your characters — come from?

A: When I was a little girl, my grandmother would give me so much love and inspire me to do my best and do unto others as you would have them do unto you. And, through her stories and our family stories, to never give up. Grandma had this spiritual wisdom that I use in all my books. And then teachers and librarians were the ones who helped me get educated because I’m a first-generation college student.

Q: What did it mean to you to win the Coretta Scott King Book Award?

A: It touches my soul, especially because I do see myself as writing about social and environmental justice. That is my mission. And Coretta, although a lot of her work was overshadowed in a sense by MLK (her husband, Martin Luther King), she was just as much a force. Even after he died, she continued to be an activist. I love her as a courageous, resilient force who kept making change, who didn’t get defeated, who just sort of rose up, not just for her family, but for so many families across America.