This post was originally published on here

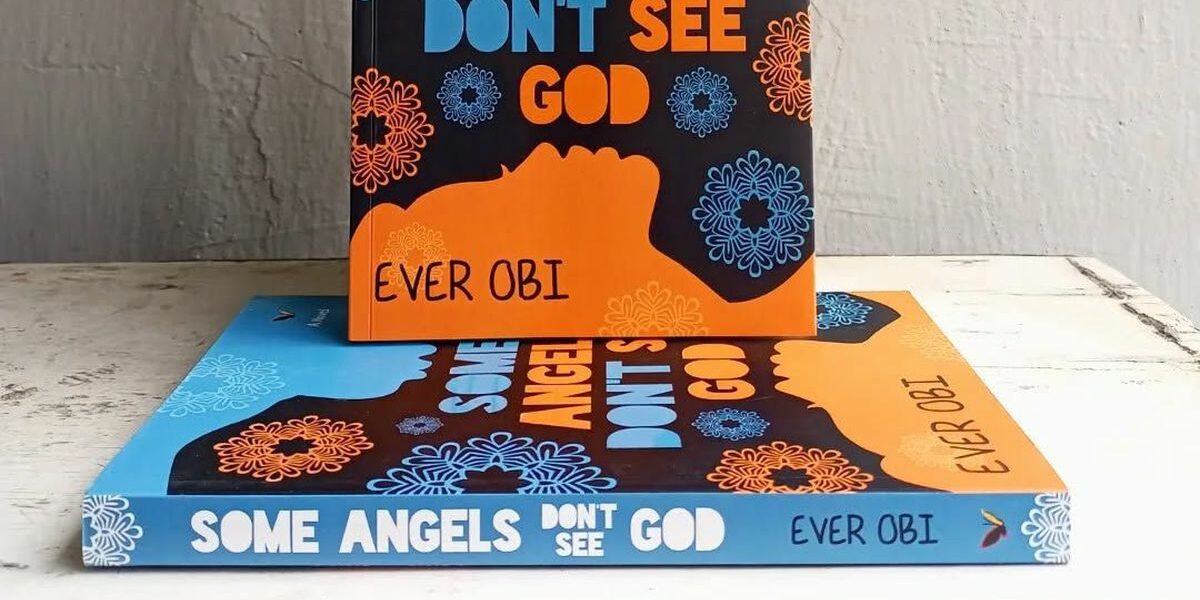

A review of Ever Obi’s Some Angels Don’t See God: trauma, love triangles, faith, and the cost of unhealed wounds.

There are books you read and move on from, and then there are books that sit with you. They follow you into quiet rooms, they tap your shoulder when you think you’ve forgotten them.

Advertisement

Some Angels Don’t See God by Ever Obi belongs firmly in the second category.

This is not just a story about trauma; it is about how trauma forms. How it seeps into love, how it distorts memory, how it bends faith. It is family drama at its rawest: incest, betrayal, guilt, ego, religious doubt, violence, yet it is written with a strange tenderness toward broken people.

At the centre of it all is Neta Okoye, an acclaimed writer whose literary success stands in stark contrast to the wreckage of her personal life. The novel asks an uncomfortable question: if angels are meant to see God, why do some walk through life convinced He isn’t looking?

The Anatomy of a Broken Childhood

Advertisement

The tragedy begins early. Too early.

Seven-year-old twins, Neta and Jeta Okoye, are left under the care of their teenage aunt, Chidinma. What begins as a so-called childhood “game” quickly reveals itself as manipulation disguised as curiosity. Their innocence becomes a laboratory for an older girl’s exploration. The adults, busy, career-absorbed parents, never notice.

That detail matters.

The abuse doesn’t end when Chidinma marries and leaves. It grows. The twins, bonded in secrecy and confusion, continue what should never have begun. By the time their mother catches them at fourteen, the damage is already layered and deep. Their father, Jikora Okoye, who had sensed something unnatural but was dismissed, dies in a reckless accident fueled by panic and rage.

Obi doesn’t sensationalise incest; he shows its ripple effects. The shame, the guilt, the warped attachment. The way one wrong act becomes a chain reaction of tragedy.

Advertisement

Ego, Violence, and the First Love Triangle

Jeta refuses to let go of the past. He romanticises it. He even references the Lannister twins from Game of Thrones as a model for their future. That detail is chilling because it shows how fiction can be twisted to justify reality.

Neta, desperate to bury their history, dates Tobe, a brilliant boy in school. But ego enters the room.

When Jeta challenges Tobe to a fight in “The Arena”, a refuse pit turned boxing ring, Tobe cannot back down. Not because of love. Because of pride. Because of the potential laughter of other boys. The fight ends in unplanned manslaughter. Tobe dies. Jeta goes to prison for ten years.

Advertisement

That entire arc feels like a commentary on masculinity and ego. How many losses in life happen because someone couldn’t endure being mocked?

Peter, Faith, and Why Some Angels Don’t See God

Peter is Neta’s second great love. Their relationship begins in betrayal; she leaves his friend Derek for him. That triangle ends in horrifying violence when Derek shoots Peter and then himself in Neta’s room.

Peter survives. Miraculously.

But survival does not restore faith.

Advertisement

After his friend Amandi disappears following an HIV diagnosis, Peter stops believing in God. To him, God becomes indifferent. Nonchalant. Absent.

Peter cannot reconcile suffering with divine protection. Neta, shaped by guilt and chaos, sees life as a carnival of injustice that only the final judgement can balance. The title suddenly feels less abstract. Some angels don’t see God because pain blinds them.

Literature as Therapy — and Confession

Neta becomes a celebrated writer. Literature becomes her oxygen. Obi crafts a quiet love letter to storytelling itself. One line from the book stays with me:

Advertisement

“Whenever her heart was broken, it was also open; like a fresh wound, it bled words. Literature did not make her forget, but it kept her sane.”

There is something brutally honest about that. Art doesn’t erase trauma. It organises it.

The Final Triangle and the Unbelievable Twist

Peter eventually returns. He wants marriage. He takes Neta home to meet his mother. Then comes a twist that, frankly, stretched my belief: a family friend recognises Neta from years ago and connects her to the man responsible for Peter’s father’s death.

The memory feels almost too sharp. Too convenient.

Advertisement

Still, it fuels the final fracture. Anita Sweets, Peter’s childhood love, re-enters from the US. Peter chooses familiarity over complication, and Neta loses him.

The Most Devastating Scene

Jeta’s release from prison should signal healing. Instead, it ushers in horror.

He moves into Neta’s apartment. Refuses responsibility. Refuses therapy. Refuses change. When she finally asks him to leave, violence erupts. The assault that follows is not described for shock — it is described for devastation. It broke me, too.

What happens afterwards is both terrifying and symbolic. Narcotics. Carelessness. Consequence. Obi refuses to romanticise tragedy. He lets it rot on the page.

Advertisement

Some Angels Don’t See God is not an easy story. It is layered with incest, manslaughter, suicide, betrayal, religious doubt, and moral ambiguity. But beneath the wreckage lies a deeply human message: unaddressed trauma does not disappear. It evolves.

The book argues for parental presence. For accountability. For forgiveness. For therapy. For confronting the past instead of running from it.

And perhaps most importantly, it asks whether suffering distances us from God, or whether our understanding of justice simply isn’t complete yet.