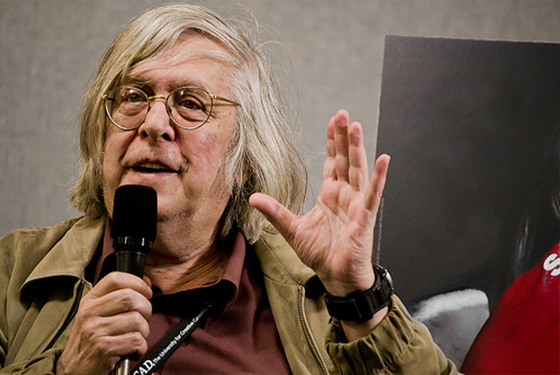

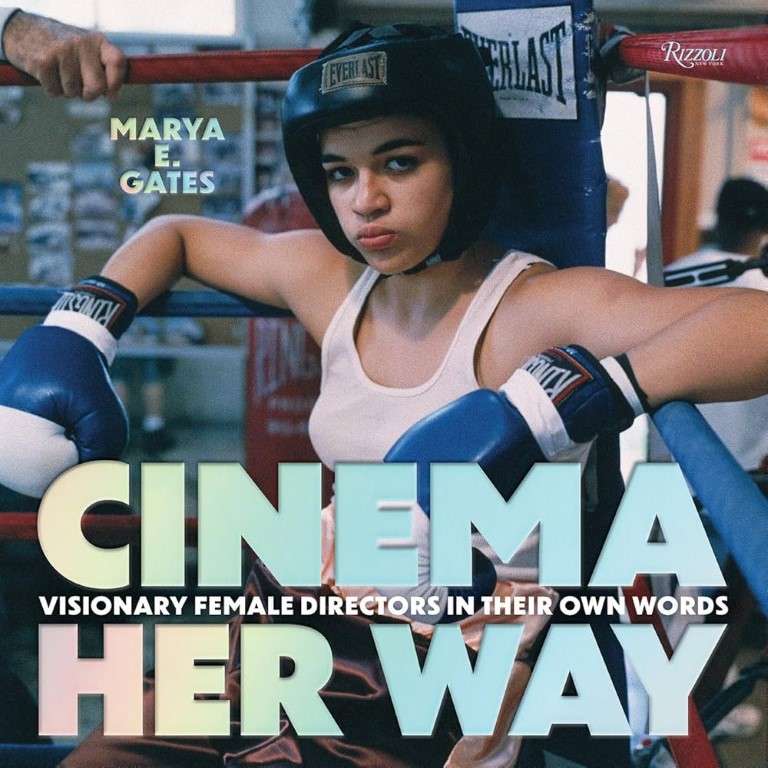

During last month’s Refocus Film Festival, Little Village film columnist Ariana Martinez had the opportunity to chat with renowned film critics Jonathan Rosenbaum and Marya E. Gates in a panel entitled “Writing on Film.” The trio’s discussion ranged from career highlights and how to approach interviewing different directors to what it means to call yourself an artist in the field of film criticism.

This is a transcript of that conversation. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Both of you came into film criticism very differently: Jonathan with newspaper publications in the ’70s, Marya with internet publications and blogs. Many critics talk about sort of stumbling into the field of film criticism. Can you walk us through how you entered this career and the push and pull of chance versus choice in your experience?

Jonathan Rosenbaum: Well, I grew up with movies, because my grandfather ran a small chain of movie theaters in Alabama, and I grew up seeing all these movies for free. From a very early age, I knew I wanted to be a writer, at least since grammar school. But it wasn’t until much later in the ’70s that I was able to join the two things together, and that was partly because I wasn’t publishing my short stories and novels, but I was publishing my film criticism.

Marya E. Gates: I grew up in the literal middle of nowhere, and it’s in northern California, three hours from pretty much anything that looks like a real business. (Except we had a movie theater and we had a video rental store called Top Hat. Rest in peace, Top Hat.) I spent my entire childhood watching movies. Going to the movie theater cost like $2. Renting five movies for five days for $5 at Top Hat video.

I was the only nerdy film kid in this town, so I adapted to the internet pretty early on. My mom was in a Ph.D. program, so we had a computer early on, and I found Yahoo Groups. I could talk about the films I was watching with people who were actually watching them. The next thing I know, because I’m a millennial, social media came about when I was in college. All of that social media became blogging, and then Twitter.

I worked in film marketing for 10 years. I left my last job at Netflix at the end of 2020 and had enough money saved to just do what I actually love, which is writing and doing my interviews. I really love doing interviews, and that’s how I am now a self-sustaining freelance film critic, which is very rare. Most people have multiple jobs. I still do some social media on the back end because it does pay some of the bills, but I love that I get to talk about what I love to people, and that perhaps some movie I recommend will change someone’s life.

So whether you’re tasked to write for a publication or you’re personally compelled to do so, what does your approach look like? Where does criticism begin for you, and then where does it go?

JR: I actually think that film critics should not, this is my own conviction, should not have either the first word or the last word about film. That basically what a film critic does, if she or he is good, is expand the options of a public discussion, and it’s a public discussion that begins before the critic comes along and continues after the critic leaves. So a critic who’s doing a good job is actually expanding or improving the options in certain ways or the quality of the discussion, but not laying down any kind of final judgments at the beginning or at the end. I like the idea of keeping things open.

MG: Half the movies I review are assigned by my editor. Half of them are movies that maybe I saw early on and begged [to write about]. But where I start, whether it’s an assignment or something I love, is thinking about what Jonathan said earlier, what was this film’s aim? Because not every film is aiming to be Citizen Kane, not every film is aiming to change the form or speak truth to power or something. Some films are cozy and were they aiming for cozy? Did it hit cozy? Are my friends who want to watch a cozy, spooky movie gonna love it? That’s what I want to highlight. What’s the audience? Do I think this film speaks to that audience? Really, for me, a film is only a failure if it didn’t hit what it was trying to do or clearly cut corners.

JR: Well, one way which we might differ on this is … in terms of intentions, I think intentionality is a big problem in criticism because I think nobody really knows. In other words, a filmmaker may say, “This was my intention.” But I don’t think anybody really knows, because it seems to me, effects are just as important as intentions.

In a way, it’s hard to be sure if you’re judging a film in terms of what it’s trying. In other words, we act like we think we know what something is trying to do, but we don’t always know for sure, and even if we did know, that wouldn’t necessarily be always the best starting point.

One of the big discoveries I made about my own work is that I was brought up to believe that if I didn’t become a film critic for the New York Times or the New Yorker, I was a failure. But, actually, today I have a much smaller audience than I had when I wrote for the Chicago Reader, but I prefer my audience now. I have a website that has an average of 1,000 people a day.

When you’re a cult writer, which I think is the category that I fit into, what you get is much more focused and even passionate. I was once asked to write a piece for the Op-Ed page of the New York Times … but I had to rewrite the piece three times to satisfy this editor, and I’ve never even wanted to reprint the piece because I feel it’s a piece that belongs to the New York Times that doesn’t belong to me.

When you write for the mainstream, you get branded by whoever you’re writing for. Whereas — I quote Manny Farber as saying that he can’t imagine a better art form — I actually consider film criticism as an art form, and that I’m therefore an artist. But that’s because I’m a cult writer that I can say something like that. If I was writing for the mainstream, I wouldn’t be allowed to get away with it.

I think it’s very interesting, the idea of meeting a film on its own terms, but how do you really figure out those terms, and who are you figuring them out for? For many critics, or aspiring critics, it may be hard to understand the realities of the field, and they can’t really wrap their heads around what a day in that life looks like. So in helping paint that picture, what have been some of your career highlights, but also some of the challenges that you’ve had to overcome?

MG: The main thing is nowadays, outlets do not pay right away, and the pay rate has stayed mostly stagnant. So I think the biggest challenge for most, unless you’re writing for the New York Times or a staff writer, is finding an outlet. I had to drop an outlet because they didn’t pay me for six months, and I had bills to pay, and I was like, I can’t write for you anymore. Finding an outlet that will actually pay you and pay you in a reasonable amount of time is sort of the biggest struggle.

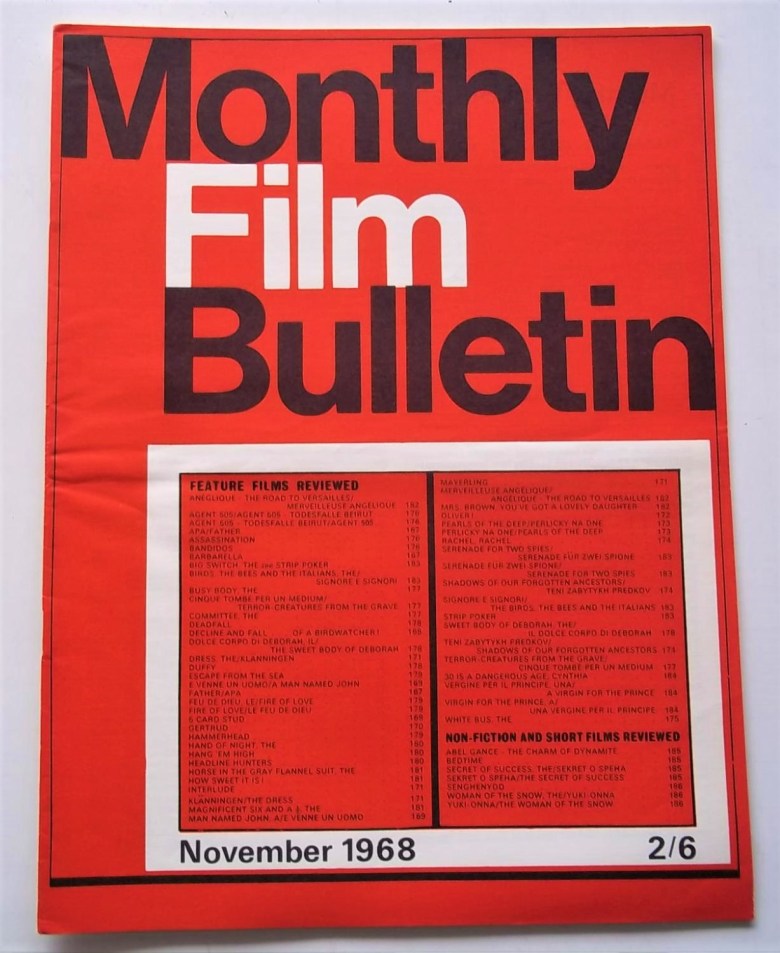

The British Film Institute

JR: To me, there was a big difference between being a staff member of a publication and being a freelancer. I was hired by the British Film Institute to work on two film magazines, Sight and Sound and Monthly Film Bulletin. I was the assistant editor of Monthly Film Bulletin, so it meant that I would have to review a lot of films that if I was just left to my own devices, I wouldn’t have been interested in going to see. The same thing was true when I first came to The Chicago Reader, particularly before I had anything like a second stringer that I had to go see everything and I had to see it to the end. I wasn’t allowed to walk out. So that obviously changes a lot.

Another problem, if you’re writing on a regular basis … you also have to make whatever you’re writing about seem important, even if it isn’t important. The week something comes out, when you review it, you have to make it seem like it’s important, whether it’s good or bad, then the next week, you’re supposed to forget all of that and make room for something else being important. So in other words, part of the job involves forgetting, not just remembering.

When somebody asks what I think of a certain film or filmmaker, I’ll look up the film on my own website to find out, first of all, whether I’ve seen it or not and reviewed it, and then even after I read my review, I still can’t remember the film. There’s a certain kind of way what you’re doing is dictated by the market and the degree to which the film industry controls the market. There’s always pressures of different kinds.

And what about the high points?

JR: One thing that was a high point for me is when I moved to Paris in 1969. At that point, I had hardly published anything. And I asked the editor of Film Comment if I could write a kind of a Paris letter, or something like this. And he said, “Sure. Try and if we like it, we’ll print it.” And they liked what I wrote. And I wound up writing for virtually every issue of Film Comment, something called Paris Journal. And just because I called it that I could write about almost anything I saw. So that was a great step, and a kind of a liberation, too, because it meant having a lot of freedom. It wasn’t like I had to cover this and that and so on. There wasn’t any agenda that was handed to me.

MG: I’ve had a few filmmakers at festivals tell me that they followed me on Tumblr, and I inspired them to become filmmakers. So that’s always fun to hear because just seeing this vast sheer number of thousands of women making films and you think only Jane Campion has done it, you realize actually no, thousands of women have done it, and it lights that little fire. So I’ve had a few filmmakers tell me that seeing that many women making films really pushed them to just keep trying. So that’s always really rewarding, because I love to connect people to films, but I love to convince people they can make films, too.

AM: Interviewing and conversations with filmmakers is a big part of both of your careers. Gates, you have this book, and I recently read your interview with Ethan Hawke, and it’s just such a great interview. It’s clear that you put so much research and effort into it, and Jonathan you’ve interviewed or spoken to heavy hitters like Orson Welles and Jean-Luc Goddard. Can you shed some light on that aspect of film criticism, the skills that you need to talk to these filmmakers that can maybe be a little intimidating?

JR: Well, filmmakers are very different from one another. There’s some who are very sensitive to any criticism you might make, while other filmmakers don’t mind if you dislike a film of theirs. That’s something Jim Jarmusch said to me, that he liked reading me, which I was very pleased by, even if I didn’t like one of his films. So I think it varies.

MG: I would agree about how every filmmaker is a little different. Some filmmakers are really intuitive on how they’ve come to whatever it is they’ve come to. Or they’re really terrible at answering questions because the film was them speaking. Some filmmakers are really technical, and they have a lot of thought, and they have a lot to share with you.

Usually, what I do when I’m prepping is I’ll read as many interviews with that filmmaker that are out there — not usually about the film that I’m asking them, but previous ones — just to see their style, and then try to tailor questions based on what kind of thinker they are. But also, if they always have a canned answer for something, I ask the canned answer back to them so they have to say something else. That’s a good trick, especially if you’re interviewing someone who has done a lot. For me, a good interview comes from a lot of prep.

JR: It seems to me that we keep referring back to “the industry,” and an awful lot of [that] is determined by what happens in film discourse: pre-existing categories. People live by them: new wave, independent versus commercial. There are an awful lot of pre-existing categories that things fall into, and sometimes filmmakers base their own careers on trying to fill the categories that are created for them, and then others haven’t figured out how to classify what they do. So it becomes the job of me or other critics to tell them what they’re doing in a certain kind of way, or at least one version of that.

MG: I actually did have a filmmaker I interviewed, Patricia Rozema for Autostraddle a couple months ago, and at the end of our conversation, she said, “Thank you for explaining myself to myself.” It’s really wonderful when you’re able to, because a lot of filmmakers, even if they’re very intuitive, they’re just putting it out there. And if you’re able to put those pieces together, if there are pieces to put together, I think it’s a really rewarding feeling.

This post was originally published on here