It was a stunning election victory. Despite a track record of lies and lawlessness, he romped home in a landslide, seeming to attract a new coalition of voters, from the conservative rural vote, to rust-belt post-industrial workers, and unexpectedly diverse sections of the cities and their suburbs.

As the chaotic but iconic blonde with a chequered personal past took up the highest office in the land, it seemed like nothing could stop him.

What could stand in the way of his big economic policy goal of national exceptionalism? He would erect trade barriers against capitalists from competing nations. He would stop freedom of movement and protect his labour force. And, though appealing to the public about their pocketbook issues, the new leader’s administration would open the way to a raft of crony appointments and favours to his super-rich backers.

Many said his coalition would dominate the nation for the next two or three election cycles.

Three years later, in 2022, Boris Johnson was gone from Downing Street. Two years after that, the Conservative Party suffered its worst election result since it was created nearly 200 years ago.

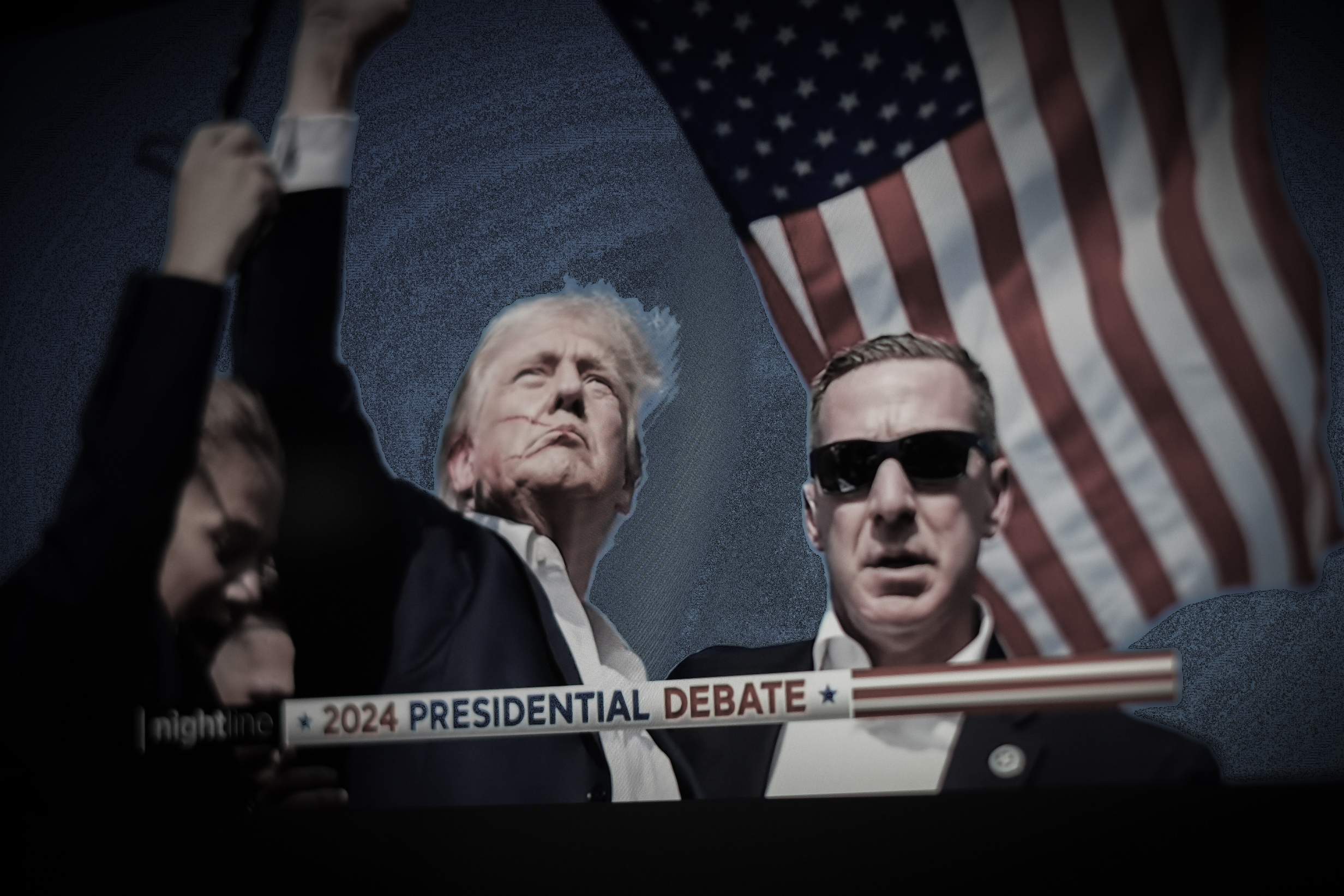

Compared to Johnson’s ‘Get Brexit Done’ General Election of 2019, the success of Donald Trump this November is much more momentous and earth-shattering. But the question of how this authoritarian populism will play out in power – and the extent of its collision with reality – is still an open one.

Trump – who once referred to himself as Mr ‘Brexit Plus Plus Plus’ and described Johnson as ‘Britain Trump’ – also vaunts an exceptionalist ‘Amerexit’: a project that assumes the US can somehow sail out of the modern world of interdependency and internationalism and go it alone.

But here in Britain, Brexit is deeply unpopular four years on – especially with those who voted for it and have been impacted by its economic shortcomings, as Byline Times revealed in a major investigation last year.

Trump has already sold to his voters the idea that tariffs on foreign goods will somehow solve the plight of inflation, though they will only aggravate it. Johnson’s Vote Leave campaign also promised lower energy and food prices, though delivered the reverse.

Trump’s plans for the expulsion of millions of undocumented migrants, mainly from Mexico and South America, are as evocative and impractical as the various hostile environments and ‘stop the boats’ schemes the Conservatives have tried here, most notably the unlawful Rwanda policy.

The US is even more reliant than the UK on migration for cheap labour, and the economic costs (let alone the moral and practical implications) of these mass deportations are likely to be much higher than the rhetorical advantage of attacking ‘outsiders’.

The contradictions are untenable.

Just as Johnson claimed to have a policy of ‘levelling up’ but was really in hock to a millionaire concierge class for donations, then rewarded with honours or government contracts, Trump’s appeal to the blue-collar vote, or black men or Hispanics, or disaffected Gen Z voters, sits ill at ease with his real alliance with billionaires and the tech ‘broligarchs’.

His coalition in 2024 remains as vulnerable as Johnson’s in 2019.

How will Trump satisfy both the hedge fund owners and the union vote? The angry Muslims who voted for him over Gaza, along with right-wing American Jews who thought he would be more pro-Netanyahu? Where’s the commonality between soccer moms fearing transgender people and the cryptocurrency porn barons? The right-wing evangelicals and the Silicon Valley transhumanists?

In this edition, Byline Times details how the Democrats lost this election, and the perils ahead for the world and the UK of another Trump presidency.

On a note of optimism, it’s worth remembering that we survived the populism of Johnson, and ‘strongmen’ remain strangely vulnerable. But on a note of pessimism, it’s also important to recognise that we experienced the onslaught of online propaganda – around Brexit and in the years that followed – while it was still in its infancy.

Back in 2016, Steve Bannon, Trump campaign manager and close ally of Nigel Farage, called the combination of his two companies – his data harvesting and microtargeting campaigning firm Cambridge Analytica and his Breitbart publications – his ‘weapons’. Both were deployed in favour of Trump and Brexit in 2016, with the assistance of Russian troll farms.

What has happened eight years on is on an unimaginably larger scale. The role of Elon Musk’s X (formerly Twitter) in promulgating pro-Trump disinformation is too stark for anyone to ignore. The now US Government’s ‘efficiency’ advisor’s statement to his platform’s users – “you are the media now” – is true in terms of both ubiquity and political impact.

In 2016, Cambridge Analytica was successful with its psychometric targeting because it hacked the data of more than 70 million users. Facebook may have closed that loophole, but Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta platforms, such as Instagram and WhatsApp, are still a major vector for unregulated and unproven conspiracy theories.

The groups that swung towards Trump, particularly young people and Hispanic voters, are disproportionately likely to get their news from Instagram or TikTok. The latter, threatened by Trump during the campaign, reportedly changed its algorithms to boost him.

So we are well beyond the point when an endorsement by the LA Times or The Washington Post will shift the dial in an election. Instead, we are, as the Observer journalist Carole Cadwalladr has been pointing out for eight years, in the full throes of an online information war over the meaning of truth, the importance of pluralism over populism, and the rule of law over unfettered oligarchy.

We have only a few short years to batten down the hatches against the storm coming over the Atlantic. The pages ahead suggest both the violence – real and psychic – of what could come, visit these shores and some of the ways we can defend British democracy against it.

It’s the fight of our lives.

This post was originally published on here