WASHINGTON —

Land Back is a global, Indigenous-led movement advocating for the return of stolen lands.

While Indigenous communities have long engaged in that fight, “Land Back” as a meme began to gain popularity in 2019.

It now describes a decentralized international movement that emphasizes treaty rights, tribal sovereignty, climate justice and cultural revival.

“Land Back is like a prism with many facets to it,” said Alvin Warren, a former lieutenant governor of the Santa Clara Pueblo in New Mexico who has spent decades advocating for the restoration and protection of Indigenous lands.

“For me, within the paradigm of the United States legal system and land tenure system, it absolutely means the restoration of full title to Indigenous people of a particular piece of land that is part of their original homeland.”

And it doesn’t stop with the transfer of legal title.

“It’s about reviving the land-based aspects of our ways of life,” he said. “It could be agriculture, it could be subsistence hunting, it could be gathering things. It is about reuniting, reconnecting us with our homeland, about undoing the many layers of separation and disconnection from our homelands that has been the goal of colonization in this country and in other parts of the world.”

Nick Tilsen, an Oglala Lakota from the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, gained national attention in July 2020 for blockading the road to Mount Rushmore ahead of a visit by then-President Donald Trump.

Shortly afterward, the NDN Collective activist launched a #LandBack campaign for “the reclamation of everything stolen from the original peoples.”

“When they [the federal government] took the land, they took everything from our people,” Tilsen said. “They took our governance structures. They took our culture. They took our language. They tried to destroy the familial structure of our people, our ability to make decisions over our food systems and our education systems.”

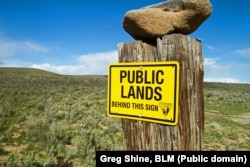

Tilsen believes the U.S. government should return all public lands, including the Black Hills, which the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty designated for the “absolute and undisturbed use and occupation” of Sioux Bands, today known as the Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires).

That treaty was nullified without the tribe’s consent in the Indian Appropriations Bill of 1876 after a government and scientific expedition confirmed the presence of gold in the hills.

Is getting that land back a realistic goal?

James Swan, a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux tribe in South Dakota, doesn’t think so.

“It’s a pipe dream,” the founder of the grassroots Indigenous rights group United Urban Warrior Society, said. “But let’s say the U.S. government does return the Black Hills. Then what?”

Swan points out that tribes are not truly independent.

“They’re part of the U.S. government,” he said. “A tribal chairman might be elected by the tribe, but he can’t do anything without the tribal superintendent’s permission, and the superintendent works for the Bureau of Indian Affairs.”

Fragmented land ownership

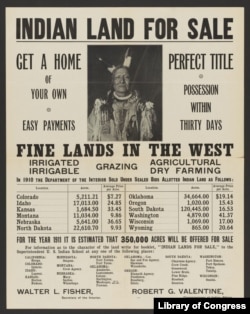

In 1887, the government allotted some treaty lands to Native American heads of household. The remaining land, over 36 million hectares, was sold to settlers or granted to newly formed states to generate funds to support public institutions such as schools, jails or hospitals. States were allowed to sell off some of their trust land “for no less than ten dollars an acre.”

Grist and High Country News recently reported that states today hold more than 809,000 hectares of surface and subsurface land on Indian reservations.

Federal oversight

The U.S. government legally owns 21 million hectares of reservation land that it holds in trust for the benefit of tribes and their members.

Federal rules limit what tribes can do with that trust land — they can’t sell, lease or transfer it without Interior Department approval and must follow strict environmental rules for many projects.

Within that trust land are restricted-fee lands that are owned by individual Native Americans or tribes but cannot be sold or transferred without federal approval and are exempt from state or local land-use regulations.

There are also fee-simple lands within those reservations that are owned outright by individuals or tribes.

“The fee-simple owner is the absolute total owner,” said Robert Miller, a law professor at Arizona State University and an expert in federal Indian law. “You have all the rights of ownership. Leave it to whoever you want. Sell it to whoever you want for a dollar or a million dollars.”

Previously, tribes were advised to purchase reservation land under a fee-simple title.

“But the Supreme Court ruled in 1992 and 1998 that if a tribe holds land under [a] fee-simple title, the state can impose annual taxes on it,” Miller said. “This has led tribes to request that the Interior Department take their fee-simple land into trust to avoid state interference.”

Pathways to land back

In December 2012, the Interior Department launched the Land Buy-Back Program, which purchased and restored to tribal trust more than 1.2 million hectares of land in 15 states over 10 years.

“The Land Buy-Back Program’s progress puts the power back in the hands of tribal communities to determine how their lands are used — from conservation to economic development projects,” Interior Secretary Deb Haaland said ahead of the 2023 White House Tribal Nations Summit in Washington.

But some Native Americans are skeptical about the program.

“It is not about returning lost lands and putting them into trust for Tribes,” Todd Hall (Hidatsa) wrote in Buffalo’s Fire, an independent news platform run by the Indigenous Media Freedom Alliance. “It is about dispossessing Individual Indians of their landownership rights and converting those rights to the collective ownership of the Tribal governments which were enacted by the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934.”

Today, tribes across the U.S. continue to buy fractional interests in trust or restricted land from willing sellers, often with help from conservancy groups and private landowners.

In September, the Western Rivers Conservancy transferred a 188-hectare former private cattle ranch to the Graton Rancheria in California for “permanent conservation and stewardship.”

Individuals also make private donations of land. In October 2018, Iowa citizen Rich Snyder voluntarily signed over land he owned in southern Colorado to the Ute Tribe.

In June, California announced it would return 1,133 hectares of ancestral land to the Shasta Indian Nation. Montana is currently considering the return of 11,800 hectares of trust land to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes on the Flathead Reservation in exchange for federal public lands outside of the reservation.

A University of Montana study in 2023 identified 44 laws placing federal public lands into tribal trust. Many, however, upheld existing rights such as access, grazing, mining or water use. Others stipulate that the land remain “forever wild” or be used only for “traditional purposes” such as hunting or holding ceremonies.

There are also legal routes to getting land back, especially with the U.S. Supreme Court establishing a key precedent in the landmark McGirt v. Oklahoma case, which reaffirmed that a large area of eastern Oklahoma still belongs to the Muscogee (Creek) Nation.

“I predict there will be 30 to 50 years of litigation over every little issue if the state, feds and tribes don’t cooperate,” Miller said.

This post was originally published on here