Bookends with Mattea Roach33:58Nalo Hopkinson: How Caribbean folktales inspired her fantastical novel, Blackheart Man

“Plot does not come easily to me” are not the words you’d expect to hear from Nalo Hopkinson, a fixture of the sci-fi and fantasy genres.

But for the Jamaican Canadian writer, known for crafting far-off worlds brimming with imagination, Caribbean folklore shapes the stories she tells.

“[Folktakes have] been told and retold for centuries,” she said on Bookends with Mattea Roach. “The plot is succinct and you can map it. So using the folktale as the spine of the story sometimes helps that way.”

In fact, Hopkinson sees folktales as the “precursors to science fiction and fantasy,” so it feels very natural to her to include them in her fiction.

“They are fantastical. They are political. They talk about how to live well with your neighbours. They talk about the abuses that people in power can do,” she said.

Those are all themes she covers in her latest novel, Blackheart Man, which takes place on the magical island of Chynchin, and draws from a Caribbean folktale told to scare children into behaving, called the Blackheart Man in Jamaica.

“It is so ubiquitous and it has this weight to it that it stuck with me since I first heard of it,” said Hopkinson.

“It’s this horrific story about this mysterious man who shows up in a black car or a black carriage, depending on what century you’re telling the story, and he hunts children and eats the living hearts out of their bodies.”

In the novel, the Blackheart Man’s sinister presence coincides with the arrival of colonizers trying to force a trade agreement — children start disappearing and tar statues come to life.

Veycosi, a mischievous and fame-seeking griot (poet and musician), fears that he’s connected with the Blackheart Man’s resurgence, and finds himself in over his head trying to stop him.

Vernacular and dialect

While the description of the scenery and people in Chynchin is designed not to situate the readers in real-life places, Caribbean dialect seeps into the dialogue of the novel.

The characters in Blackheart Man speak in different levels of vernacular depending on their social class, which Hopkinson described as the most fun part of writing the novel.

“You can recognize the minute someone opens their mouth a little bit about what kind of background they come from,” she said — and she wanted to embed that recognition into the story.

“Writing a book is hard, but the language was just a lot of fun to play with and trying to come up with different registers depending on people’s social access because that’s how we speak.”

Her use of vernacular was also inspired by her father, Abdur Rahman Slade Hopkinson, a Shakespearean-trained actor, poet and playwright who was part of a literary movement in the Caribbean to respect vernacular speech.

“Writers and linguists were fighting for respect of the way people speak, as not being bad English, but having its own grammar rules, its own logic, its own vocabulary. And so I became comfortable with that, which made it easier for me to be able to do what I did in the language in Blackheart Man.”

Becoming a writer

Her father’s place in the literary and artistic world not only helped with this aspect of her novel, but also gave her the space to become a writer herself.

Though her father had died by the time she started writing, his creative pursuits paved the way for her creative endeavours.

“The concept of having a relative who was a writer was not new to my mother,” said Hopkinson. “I know a lot of my friends have to fight for the respect of their relatives and to be taken seriously. And I don’t have to. And it’s not expected that because I publish something, I’ll be a millionaire.”

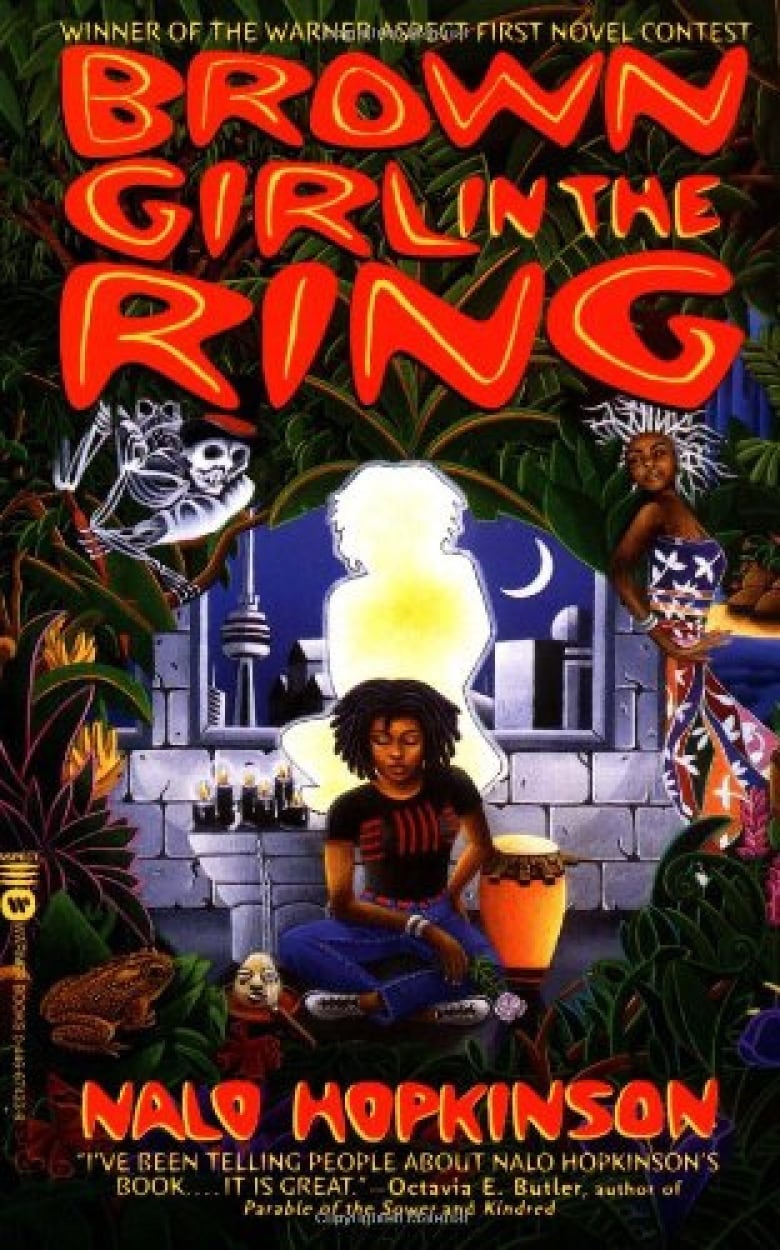

Since her debut novel, Brown Girl in the Ring, which won the Warner Aspect First Novel Contest and was defended on Canada Reads in 2008 by Jemeni, Hopkinson has published many novels and short stories, including Sister Mine, Midnight Robber, The Chaos, The New Moon’s Arms and Skin Folk.

In 2021, she won the Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master award, a lifetime achievement award for science fiction, becoming the first Black woman to be honoured with the title and the youngest-ever Grand Master at age 60.

“I know I represent a lot to people who didn’t think they could do what I’m doing for various reasons,” said Hopkinson in a 2021 interview on The Current.

“People from marginalized experiences like I am, being Black, being an immigrant to North America, being female, being queer, being over a certain age, having some level of disability. It’s something I do take seriously.”

WATCH | Nalo Hopkinson wins the 2021 Grand Master Award:

Hopkinson’s literary career hasn’t been without challenges — she’s grappled with homelessness and was unable to work at times because of chronic illness. But she’s still drawn to telling stories regardless and rejects the pressure that artists must always be creating something better than what came before.

“That’s unrealistic,” she said on Bookends. “Everything you put out presents you with a different challenge than the thing that came before, and it might be stronger or it might be weaker. And that’s fine. That’s part of the way that artistic development grows.”

As she adds her latest novel to her shelf, Hopkinson is most proud of the fact that she’s been able to publish this many books that have made a difference to people.

“It means a lot that sometimes people come up to me and my work has meant something profound to them,” she said. “That’s a gift they give back to me to let me know that something that I’ve done has touched them.”

“Because when you’re in the traces and sitting in front of that screen and staring at it ’till your eyes bleed and trying to figure out what to write next in their story, the effect it might have on people is far, far away, and you never know what it is that’s going to touch somebody.”

This interview was produced by Ryan B. Patrick.

This post was originally published on here