Who was Ray Bradbury?

According to Wikipedia, he was born in 1920, spent most of his early childhood years in Waukegan Illinois, then moved to Los Angeles at the age of 14. He dreamed of being a writer from an early age, and began publishing science fiction in 1938, continuing to build his career during the wartime years because bad eyesight exempted him from the draft. In 1951, so, at the age of 31, he published The Fireman as a short story, then was invited to extend its length to be publishable as a novel, which occurred in 1953 as Fahrenheit 451.

In recent years, this book has been claimed to be seen as prophetic, foreseeing the “censorship” of books in the U.S., with endless caterwauling about “Banned Books Week” and the unfairness of schools removing from their collections such books as Let’s Talk About It, This Book is Gay, and All Boys Aren’t Blue, the first two of which contain explicit instruction on such things as accessing porn and anonymous hook-ups, and the last of which features as a primary plot point the author of the memoir having identity-affirming gay sex (in explicit detail). Indeed, the fact that there exists a dystopian book which contains as its premise the burning of books is used as prima facie evidence that any restriction on youth reading material is bad.

As it happens, a couple weeks ago, my son’s school performed as a radio play an adaptation of the book, with a note in the program stating that the book is particularly relevant now because of the practice of parents challenging books. (Never mind that the rise in “number of books challenged” is a direct consequence of the increasing number of books directed at children or perceived by teachers/librarians as appropriate for children which are sexually explicit . . . ) And I pulled the book off the bookshelf for a quick reread.

Why, in Bradbury’s telling, did the United States of the future choose to burn books? It is not because of a desire to persecute sexual or ethnic minorities (the claim of modern-day “anti-book banning” activists), or to protect a dictatorship from opposition (the practice of real-life dictatorships). Instead, the firehouse captain Beatty tells fireman Montag (starting on page 51 of my “60th anniversary” edition), that the history of book-burning followed a different trajectory.

“It didn’t come from the Government down. There was no dictum, no declaration, no censorship, to star with, no! Technology, mass exploitation, and minority pressure carried the trick, thank God. Today, thanks to them, you can stay happy all the time, you are allowed to read comics, the good old confessions, or trade journals.”

Why did that happen? The advent of mass media, beginning with photography, then movies, radio, and television, each providing more “eyes and elbows and mouths” and

“films and radios, magazines, books leveled down to a sort of paste, pudding norm. . . . Books cut shorter. Condensations. Digests. Tabloids. Everything boils down to the gag, the snap ending.”

Beatty continues:

“School is shortened, discipline relaxed, philosophies, histories, languages dropped, English and spelling gradually neglected, finally almost completely ignored. Life is immediate, the job counts, pleasure lies all about after work. Why learn anything save pressing buttons, pulling switches, fitting nuts and bolts?”

Why, then, ban boks?

The advent of this popular culture and fun and simplification and entertainment meant that

“the word ‘intellectual,’ of course, became the swear word it deserved to be. You always dread the unfamilar.”

Because, Beatty says, the brightest children were “better” than the others, they must be tamped down, prevented from causing harm or even making others feel bad.

What’s more, in order to preserve “happiness” in society, minorities had to be prevented from being upset.

“Colored people don’t like Little Black Sambo. Burn it. White people don’t feel good about Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Burn it. . . . Serenity, Montag. Peace, Montag.”

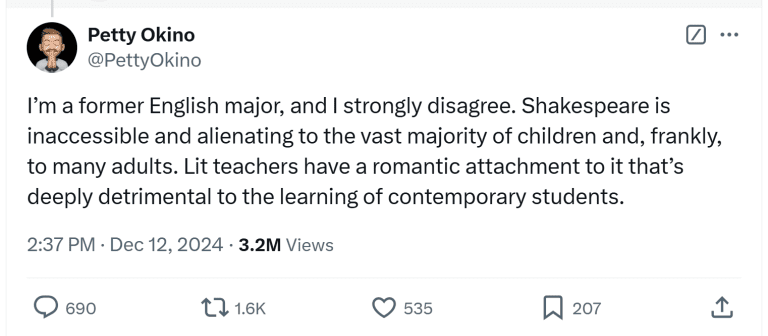

So what is the actual present-day analogy in the book? Not the practice of, or desire of parents to restrict books with explicit sex from high schools. Instead, it sounds a heck of a lot more like Bradbury is warning us of the impact of a country with its young adults addicted to Tik Tok and other videos, paired with the concern of policymakers and other “experts” with weeding out materials that are “offensive” to minorities. And ironically pretty much at the same time as I got back from this performance there was a claim being circulated on Twitter that schools should discontinue teaching Shakespeare:

Of course, both interpretations — the “Fahrenheit 451 means we should stop even small-scale book bans because it is the path to total destruction of the written word” version as well as “Fahrenheit 451 is a warning of the consequences of short-form videos replacing reading” — rely on Bradbury being a prophet, having the ability to foresee the long-term impact of short-term trends and decisions. And I don’t know that there’s necessarily evidence that a 31 year old science fiction & fantasy writer had this ability. We don’t know what the long-term effect will be of the dramatic decline in the degree to which Americans, especially children and young adults, read, and the rise of Tik Tok and other videos for entertainment and as a news source. Teachers consider watching a Romeo & Juliet movie to constitute “teaching Shakespeare,” and likewise in other ways have shifted to “teaching” by means of assigning videos to watch. Reports are growing that even in the short time that ChatGPT has become available, students have become dependent on it. And so on. But the “solution” isn’t found in a dystopian novel.

This post was originally published on here