The mother-and-daughter team of DeAnne and Michelle Sherman have co-authored several books for teenagers and adults who are impacted by family members with mental health issues. Daughter Michelle was first motivated to create resources for families when she realized that loved ones in waiting rooms of mental health clinics at the Veterans Administration hospital — where she treated people with post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental illnesses — tended not to have resources for their own grief, fear, and uncertainty.

What motivated you to write (and re-write) your books?

Michelle: I’ve been a clinical psychologist for about 30 years. While I was working at the VA Hospital in Oklahoma City in the late 1990s, I saw many family members sitting in the mental health clinic waiting rooms; the commonality of their needs and challenges and loneliness really spoke to my heart. I started creating family education programs for family members that offered support and information about helping someone who has experienced trauma or has a mental illness, as well as tools for taking care of themselves.

What books have you written together?

Michelle: In the early 2000s, my mom and I wrote three books for teenagers — one for those with a parent who has experienced trauma, one for teens whose parent has a mental illness, and one for those whose parent has a military deployment. One area of concern is that children of parents with mental illness are falling between the cracks. So, we recently released the second edition of our book for these teens, I’m Not Alone: A Teen’s Guide to Living with a Parent Who Has a Mental Illness or History of Trauma.

We have a new resource published by Johns Hopkins University Press, Loving Someone With a Mental Illness or History of Trauma: Skills, Hope and Strength for Your Journey. We hope it is experienced as a support group in a book — giving readers opportunities to read, write, and reflect upon interactive exercises. It includes reflections of people’s lived experiences as family members.

Mom and I work really well together in terms of complementing our approaches, our thoughts, our experiences, how to frame things, how to write things in a way that we hope people will hear. Mom is an educator who knows how to engage people in a way that will be meaningful for them. So it’s been a lovely mother-daughter journey.

Where do you see optimism, and needs and gaps, in Minnesota in terms of addressing mental health issues?

Michelle: Thank goodness for Sue Abderholden (director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness NAMI-MN) for all that she does as an advocate. She is there fighting, writing letters to the editor, and meeting with legislators.

Minnesota has many outstanding organizations, programs, and advocates working to improve mental healthcare across our state. One example is the growth of Emergency Psychiatric Assessment, Treatment, and Healing (EmPATH) units that complement traditional emergency departments and allow people to have assessment and treatment planning in a calm, low-stress environment — sometimes precluding the need for a psychiatric admission.

However, there continue to be significant gaps and opportunities for improvement. I continue to hope we can address the siloed nature of mental health care. We have adult providers, and children providers, and often they really don’t talk to each other. For example, a psychiatrist could be doing a quick medication check with a parent and doesn’t have time to ask: How are the children doing?

Secondly, there’s a huge shortage of mental health professionals who reflect the clients we want to serve, including ethnic background, language, and skin color. We need to provide opportunities for education and licensure for a diverse population of people. Many mental health professionals are going to retire in the next decade, so this need will be even more important.

DeAnne: Stigma and discrimination are still alive and thriving, but some progress is being made. When we wrote the 2nd edition of our book for teens, we had 15 or 20 teens read different chapters and give us feedback. It’s amazing how articulate they were, and how informed they were about mental illness — a lot different from the youth who read our first edition, who had much less understanding of emotional problems or trauma.

DeAnne: Stigma and discrimination are still alive and thriving, but some progress is being made. When we wrote the 2nd edition of our book for teens, we had 15 or 20 teens read different chapters and give us feedback. It’s amazing how articulate they were, and how informed they were about mental illness — a lot different from the youth who read our first edition, who had much less understanding of emotional problems or trauma.

I think teens are more comfortable talking about their own mental health problems, or their parent’s mental illness. That is really good news.

One of our early teen reviewers was going into seventh grade and said, “Don’t forget to include the concept of giving grace.” My jaw dropped. Our book had been reviewed by 30 people, including leading psychologists in the United States. No one came up with the concept of grace except this lovely seventh grader. So we added that topic to both of our new books for adults and teenagers.

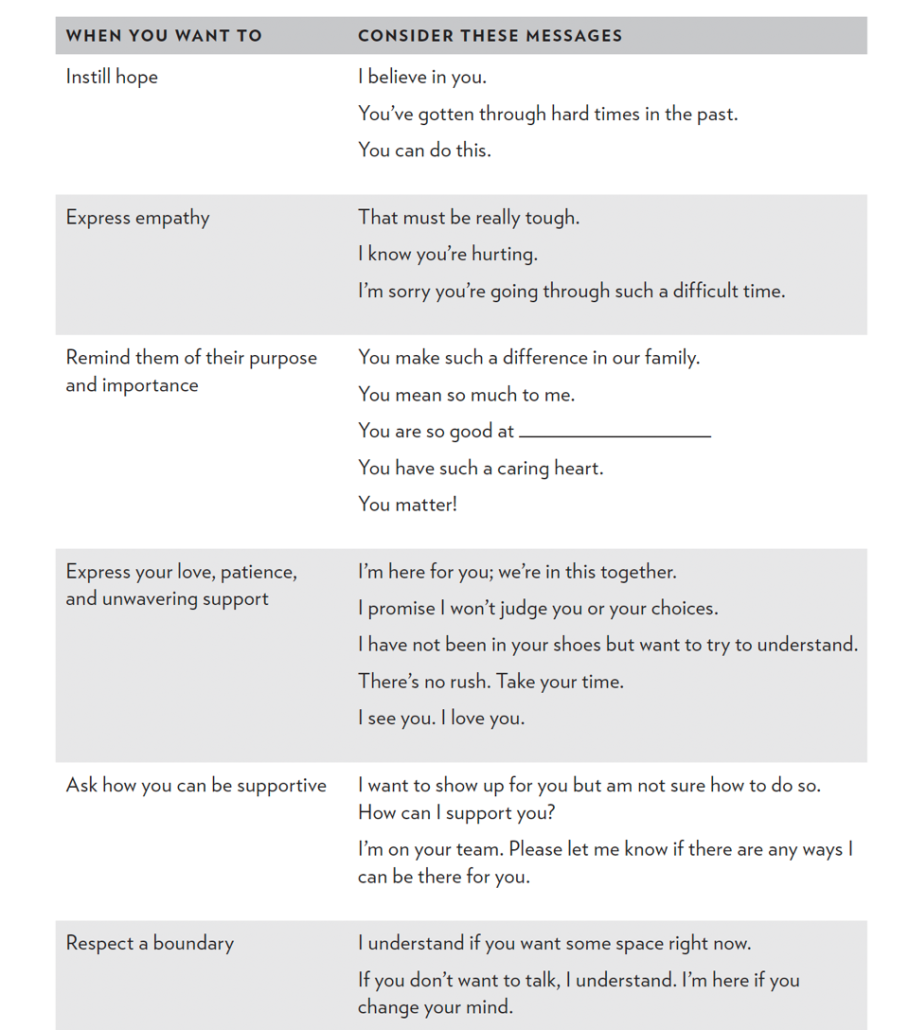

Giving a person grace does not make it okay to be dismissive, abusive, or unkind. Everyone deserves to be safe in their home and treated with respect. It does mean, however, that it can be helpful to give someone the benefit of the doubt, to pick your battles, and to choose kindness.

Given the incomplete nature of mental health treatment in the U.S., what advice do you have for friends and family of loved ones who are challenged by mental illness and trauma?

Michelle: As we think about PTSD and mental illness in general, one of the most important parts of recovery is connection and relationship. I’m not minimizing the importance of medications, evidence-based psychotherapies, group support — but a huge part of recovery is having a safe place, a place of being seen.

For many people with mental illness and PTSD, there’s the fear of stigma and discrimination and how it might impact one’s career. There’s a sense of ‘I need to pull myself up by the bootstraps and get better by myself.’ There’s shame and fear of other people finding out and judging you.

The VA has a slogan of “It takes the strength of a warrior to ask for help,” which really resonates with us.

However, there’s also the reality of many barriers to people seeking mental health care: a clinic being open eight to five and not being able to leave your job to get to appointments, or insurance not covering the service or provider you seek. It can take a lot of perseverance to find care, which can be especially hard when you’re emotionally overwhelmed .

I heard the story recently of a man whose brother is homeless, is experiencing serious mental illness, and not wanting help. It is hard for family members to take care of themselves, while also trying to help a loved one. One of the challenges is that mental illness can be cyclical and unpredictable.

We do know that trying to convince people to access professional help usually doesn’t work. It’s all about strengthening your relationship with your loved one, building trust, and focusing on what is important to them. For example, they may be willing to go to a doctor for help with sleep, and that’s a great place to start.

DeAnne: We have a story in our book for adults about a family in which the daughter was in the hospital with leukemia and the community was very supportive, including setting up a meal train. About 18 months later, the father was in the hospital with an episode of psychosis. No one came by to support the family — not because they didn’t want to, but because they didn’t know what to do or what to say. So we offer such examples of stigma and discrimination in both of our books. We encourage readers to be specific in letting others know how they can be helpful: “I would love you to pick up a few things at the grocery store.” “I’d love you to take my child to dance class.” “Could you mow my lawn or shovel the snow?”

In another example, a young boy was hospitalized with mental illness. The mom reached out to her sisters and asked them to visit him in the hospital. They were concerned that they didn’t know what to say. The mom said to her sisters, “Just be yourself and go love him.” These aunts had a lovely time with their nephew, just being themselves.

What do you wish more people understood about mental health?

Michelle: One in four people has mental illness at any given time. Half of us will have mental illness at some time in a lifetime. So it’s very common. Pretty much everybody knows someone who has a mental illness or trauma. Part of why we created this support group-in-a-book was to help people feel they aren’t alone. If you live in a rural area with few resources, or there are schedules or stigma, a support group might not be an option.

Depression is like the common cold — it is a huge issue. Caregivers also are at a higher risk for experiencing depression and anxiety themselves. The essential reminder for family members is that you have to balance supporting your loved one with your own well-being — go to the movies, take a walk, play with your dog, be with other family members. Depression can be really hard to live with. It can be about irritability, crabbiness, shortness, high temper, as well as sadness, lack of interest, withdrawal.

DeAnne: We talk a lot about self care for the family members in our books. That can mean going into your office, closing the door, turning the lights off, and just breathing for five minutes. Or going for a quick walk, to center yourself outside or in nature. None of this stuff is easy. We do not say, “If you take care of yourself, things are going to be okay.”But it makes a difference. Maybe it’s a pedicure, or going to a sports bar, or the theater. Even just small acts of self care are essential.

Resilience can be learned. It’s the act of getting through a difficult situation and bouncing back on the other side. It’s about good messages you give yourself: “I can do this. I’ve done this before. This isn’t the end of the world. Let’s break it apart and take a look at what’s going on. I don’t have to go through this by myself.”

Details: SeedsofHopeBooks.com

Sherman books

This post was originally published on here