This post was originally published on here

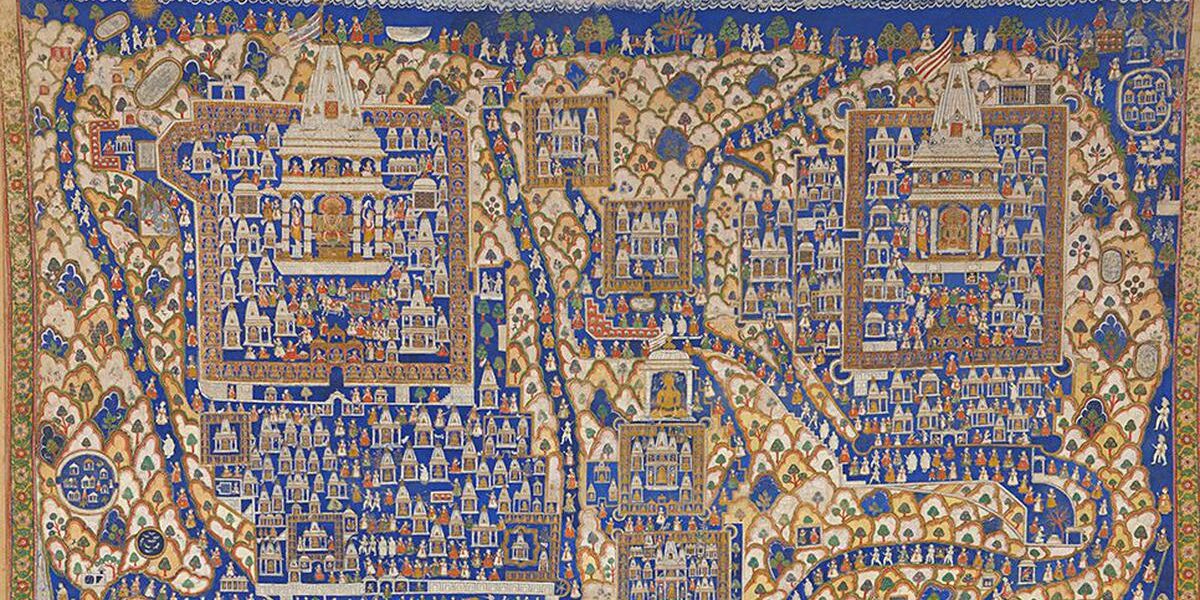

Shatrunjaya Pata, created 1870-1900

|

© John and Fausta Eskenazi/Roli Books

The ideas behind early Indian cosmographies often predated the invention of print. These were not maps of physical terrain but of inner worlds – depictions of the soul, the cosmos, and moral order. Dense with meaning and rich in iconography, they demand time, reflection, and interpretation. Their presence reminds us that the desire to map existed not only to understand where we are – but who we are. Long before printed maps, there was a human instinct to situate ourselves in a world both real and imagined. These maps compressed worldviews, philosophies, and cultural cosmologies into an intricately illustrated form. It’s easy to get lost in their many layers – depictions of heaven and hell, the cycles of rebirth, or diagrams of the human journey through time and space. They remind us that the origins of mapping lie not only in the desire to chart coastlines or claim territory, but also in the deep human impulse to understand one’s place in the cosmos.

In the East, this knowledge was often passed down orally or preserved in manuscripts written in regional scripts – later to be illustrated as the cosmographies seen in this book. In the West, the tradition took form in the mappa mundi that blended religious doctrine with early attempts at geographic understanding. These medieval world maps, often centred around Jerusalem and shaped more by theology than topography, are among the earliest surviving examples of humanity’s need to draw what it cannot yet fully grasp. They illustrate a truth that resonates through every age of map-making: long before we could measure the world, we imagined it.

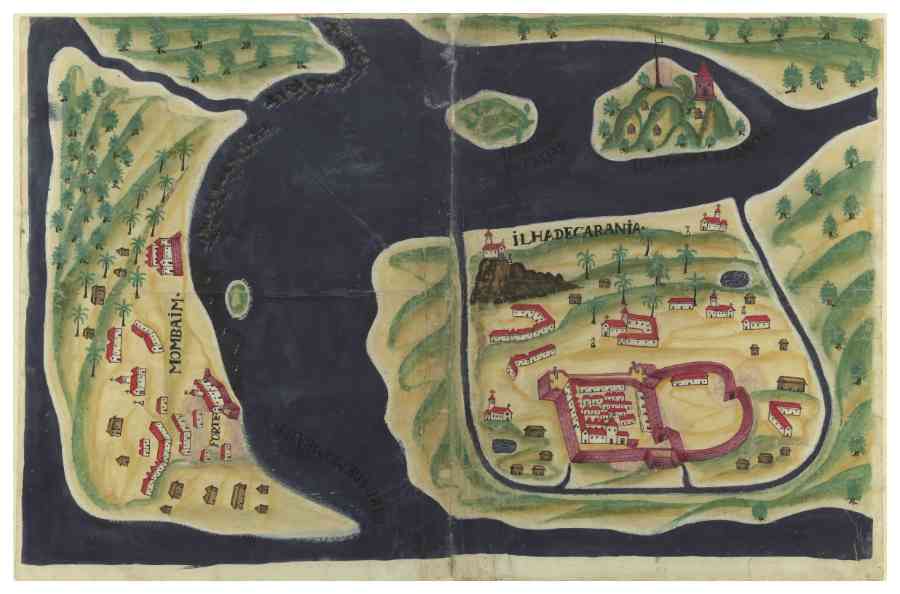

Among maps seen across the first three sections of the book, some show a wildly distorted geography of the world, placing continents and countries at odd angles or expanding certain regions unnaturally. But these were not simply errors – they were experiments. The earliest cartographers were in fact grappling with fundamental challenges: How do you flatten a round earth? How do you capture the known world on a finite page? The answers came in the form of projections – creative solutions that laid the foundation for modern cartography. What we today see as ‘mistakes’ were, in their time, remarkable steps in an evolving understanding of the world. And as Europe’s appetite for exploration grew, so did its desire to visualize, own, and name the world. Map-making fused art, geography, science, theology – and even anthropology – into a single act of creation.

This book offers two distinct forms of storytelling. One unfolds through each map as read individually – examined for its detail, its purpose, its moment in time. The other emerges as the maps are read in sequence, allowing patterns to surface, histories to echo, and a larger narrative to take shape. The maps have been carefully arranged to enable both experiences. This is not merely a journey through the shifting landscapes of India – it is also a journey through the evolution of map-making itself: its changing purposes, materials, craftsmanship, and iconography. Some revelations come instantly; others, only after a second or third return, when new details draw the eye and forgotten symbols begin to speak.

Take, for instance, Map of the Native Town of Bombay (Map 227). At first glance, it appears straightforward – a layout of streets, neighbourhoods, and names marked on a key. But linger longer and you’ll notice something more – narrow lanes crowded together, tanks carefully plotted across the map’s surface, narrating the tale of an inadequate water supply. This map was not just a depiction of the native town in the 1850s – it was a statement, a demand. It made visible the urgency of Bombay’s sanitary conditions and the need for urban reform. It is through such maps that policy was shaped, and cities reimagined. And so, it is with many maps in this book: they reward return. Look again, and you will see more. The maps will invite a dialogue – urging us to trace every corner, symbol, and visual cue for the stories they hold.

As archivists, curators, and storytellers, our hope is to bring back into focus the repositories that safeguard this knowledge – institutions that, if nurtured and supported, can help us reimagine our place in the world. And perhaps, in doing so, there may also be an opportunity to reclaim a lost art: the weaving of stories into our maps, even the most precise ones – treating geography not just as data, but as a living, evolving narrative and using maps as canvases. We now live in an era of GPS, satellite mapping, and AI-generated geographies. And yet, there’s a quiet revival happening.

Artists, designers, and scholars are returning to cartography – not just to map space, but to map memory, imagination, migration, and meaning. Perhaps this is the future of mapping: not just charting where we are, but tracing how we came to be – bringing us full circle to the spirit of the earliest maps you will encounter in the first section of this book.

Excerpted with permission from India Through Iconic Maps, Deepti Anand, Sanghamitra Chatterjee, contributing author Juhi Valia, Roli Books.