This post was originally published on here

The stories one associates with the Malayalam film industry these days are joyous — of it making yet another movie that defies conventional box office logic, of it telling a familiar story in unexpected ways, or of it conquering some uncharted territory. But almost a century ago, its beginnings were steeped in tragedy. J.C. Daniel, who became Malayalam cinema’s first filmmaker with Vigathakumaran (1930), never made another film. P.K. Rosy, the first Malayali heroine, had to flee the State after facing attacks from upper-caste men who couldn’t stand a Dalit woman playing an upper-caste character. Her face was never seen on screen again.

Cinema might have seemed a doomed enterprise back then in these parts — in the yet-to-be-formed Kerala, divided between princely states and the British Raj. The people of this land, fettered by feudal, casteist, and royal oppression, took their own sweet time warming up to one of the youngest art forms. Renaissance movements were only beginning to bring about progressive changes, while the socio-cultural-political churn birthed by Communism was still years away.

Malayalam cinema, now being discovered and garnering praise from the unlikeliest of places, became what it is today through multi-layered churns over the years, both within the industry and in the larger Kerala society. For instance, what is currently being hailed as the new wave in Malayalam mainstream cinema draws a good amount of inspiration from the middle-of-the-road cinema that became popular in the 1980s, taking in the best elements from the mainstream and independent streams of cinema.

Literary influence in cinema

Even when the industry was taking its baby steps, it pivoted in a starkly different direction from the rest. Mythological films were the mainstay in some industries back then. In Malayalam cinema, other than a handful of mythological films, relatable family dramas and socially realistic films were made in large numbers right from the early 1950s. It often drew its material from literature, a trend that became visible as early as the second-ever film made in Malayalam, Marthanda Varma (1933), based on C.V. Raman Pillai’s classic novel.

Over the years, some of the major literary figures in Malayalam, including Uroob, Vaikom Muhammad Basheer, Ponkunnam Varkey, P. Kesavadev, Thoppil Bhasi, and M.T. Vasudevan Nair, as well as contemporary writers such as P.F. Mathews, S. Hareesh, and Santhosh Echikkanam, have lent depth to screenwriting in Malayalam. The role that these writers have played in shaping the kind of stories Malayalam cinema told and the particular direction the industry took is immense.

When legendary poet P. Bhaskaran and Ramu Kariat joined hands to make Neelakuyil (1954), one of Malayalam cinema’s landmark films, Uroob was the one who penned the screenplay. The film took casteism by its horns when it was very much visible all around. A progressive outlook was thus coded into a significant stream in Malayalam cinema from its early days. It might not be a coincidence that the three brains behind the film were active in the Indian People’s Theatre Association, the All India Progressive Writers Association, and the Kerala People’s Arts Club.

Miss Kumari and Sathyan in a still from the 1954 film Neelakuyil. The film was directed by Ramu Kariat with screenplay by poet P. Bhaskaran.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

The early 1950s witnessed the making of several films such as Navalokam and Rarichan Enna Pouran, which questioned the status quo of feudal exploitation of the labouring classes and generated anger against their eviction from the land that they had tilled and lived on for generations. In a way, films (although to a much lesser extent than plays) also played a role in building the momentum towards the historic land reforms and other progressive measures initiated by the first Communist government that came to power in Kerala in 1957.

Parallel to this progressive stream, the early form of a more commercial stream of Malayalam cinema was being shaped by two production studios that ruled over the industry for over two decades. Not surprisingly, two enterprising businessmen were the driving forces behind this stream, which had its eyes set more on box office returns than on social change. Kunchacko set up Udaya Studios in Alappuzha, in Central Kerala, in 1946, while P. Subramaniam set up Merryland Studios in Thiruvananthapuram in 1951. Predictably, the two studios, in their competition to outdo each other, would also decide the direction the industry in general would take in those decades.

This early era of Malayalam cinema also witnessed the emergence of the first generation of film stars — Prem Nazir, Miss Kumari, Sathyan, Madhu, Sheela, Sarada, and a host of others who evolved distinct acting styles of their own at a time when they did not have many references for acting other than the loud performances witnessed on stage. Master technicians like cinematographer A. Vincent, who later became an accomplished filmmaker too, elevated an industry that was still running on limited money. The natural brilliance of musicians such as M.S. Baburaj, Devarajan, K. Raghavan, and Dakshinamurthy, and lyricists like P. Bhaskaran, Vayalar Rama Varma, and O.N.V. Kurup further took cinema to the masses.

K.S. Sethumadhavan found both box office success and critical acclaim with classics such as Yakshi, Anubhavangal Palichakal, and Oppol, while filmmakers like J. Sasikumar and M. Krishnan Nair, both of whom directed over 100 films, appeared to have found that secret recipe for commercial success. Ramu Kariat turned Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai’s acclaimed novel set in the coastal belts of Kerala into Chemmeen, which became the first South Indian film to win the President’s Gold Medal for Best Film in 1965.

Sheela and Madhu in Chemmeen. The 1965 film, adapted from Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai’s novel by Ramu Kariat, was the first South Indian film to win the President’s Gold Medal.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

Emergence of film societies and independent cinema

The opening of the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) in Pune in 1960 would soon have its reverberations in Malayalam cinema as well. Among the second batch of students at FTII was Adoor Gopalakrishnan. Taking forward the idea of a film society movement that he and a few others had worked on at the institute, Adoor and his friends launched Chitralekha, Kerala’s first film society, in 1965. More than just a platform to showcase films from across the world to the public, it was a calculated initiative to change how Malayalis looked at the medium — to convey to them that another kind of thoughtful cinema was possible. Spurred by the spirit of Chitralekha and the screenings that they organised across the State, film societies sprang up throughout Kerala, even in remote villages.

Adoor Gopalakrishnan co-founded Chitralekha in 1965, Kerala’s first film society that transformed how audiences viewed cinema. The co-operative produced his landmark debut Swayamvaram in 1972.

| Photo Credit:

Nirmal Harindran

The Chitralekha film co-operative produced Adoor’s debut film Swayamvaram in 1972, a work that is widely considered the initiator of the new wave in Malayalam cinema. In its aesthetics as well as in its treatment of the story of a young couple facing up to the cruel realities of life, Swayamvaram was a clear break from the melodramatic fare that Malayalis were used to until that point. The film won four National Awards that year, including the Best Film and Best Director trophies. Over the next few decades, Adoor would build an enviable filmography, with some of the most acclaimed films including Elippathayam, Kodiyettam, Anantaram, Mathilukal, Vidheyan, Kathapurushan and Nizhalkuthu, most of which have won accolades for Malayalam cinema at international festivals.

Mammootty as writer Vaikom Muhammad Basheer in Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s 1990 movie Mathilukal.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Just like in other film industries that witnessed the emergence of a new wave, Malayalam cinema also opened up like never before, with a new crop of filmmakers who experimented with the form and used the medium to tell the kind of stories that were never considered worthy of cinema before. Avant-garde filmmaker John Abraham, another FTII product, also made his debut in 1972, with Vidyarthikale Ithile Ithile. He and his friends at the Odessa Film Collective, who did not believe in the traditional film production and distribution mechanisms, turned the entire chain of activities into a people’s movement. To raise funds for his last and best-known film Amma Ariyan (1986), the collective staged street plays and screened films through which voluntary contributions were collected.

Among the crop of trained filmmakers was G. Aravindan, a maverick who never went to film school but brought to his cinema the depth of his talents ranging from art direction to classical music and cartooning. All of this is evident in the colourful world of the little ones in Kummatty (1979), the mystical spaces conjured up in Esthappan (1980), the guilt-ridden saga of Chidambaram (1985) and his last film Vasthuhara (1991), a classic on dispossessed refugees that has much contemporary relevance.

Middle-of-the-road cinema

Independent cinema and mainstream cinema in Malayalam did not remain in silos, but the influences of each seeped into the other. It was only a matter of time before a new set of filmmakers arrived on the scene, imbibing the things they liked from both streams into their works. K.G. George, Bharathan, Padmarajan, Mohan and a few others held sway throughout the 1980s.

Master filmmaker K.G. George defied genre conventions, creating investigative thrillers like Yavanika, sharp political satires, and groundbreaking women-centric films like Adaminte Variyellu that addressed class and gender.

| Photo Credit:

Thulasi Kakkat

K.G. George, considered one of the masters, was never bound by genre conventions, jumping with ease from investigative thrillers to political satires, campus romances and family dramas. George made his debut with Swapnadanam (1976), an unconventional psychological drama. Psychology would remain a prime concern in many of his films, especially in Irakal, about a raging young man whose anger seems to be incubated within an oppressive, patriarchal family. George’s Panchavadi Palam remains one of the sharpest political satires ever made in Malayalam. Counted among the classics of Malayalam cinema is George’s Yavanika (1982), a layered investigative thriller set within a drama troupe. But perhaps among his best contributions are his women-centric films like Mattoral and Adaminte Variyellu, which is also remarkable in not losing sight of class issues.

The careers of Bharathan and Padmarajan are intertwined in more than one way, with the former nudging the latter, already a literary star, to pen his debut film Prayanam (1975). Before long, Padmarajan came into his own by directing Peruvazhiyambalam (1979), which looked at how the masses usually came under the spell of strongmen. His filmography is filled with village fables like Oridaththoru Phayalvaan (1981) and Kallan Pavithran (1981) and Arappatta Kettiya Gramathil (1986) with neatly etched characters, as well as crime thrillers like Season (1989), heart-wrenching dramas such as Moonnam Pakkam (1988) and bold ventures like Deshadanakkili Karayarilla (1986), which explored the close relationship between two teenage girls. But his most remembered films continue to be the bold Namukku Parkkan Munthirithoppukal (1986) and Thoovanathumbikal (1987), both of which had Padmarajan at his romantic best.

Bharathan caught the imagination of the young crowd with Rathinirvedam (1978), written by Padmarajan, which became a major trendsetter with its coming-of-age story, with an added dose of sensuality. The duo had yet another successful run with Thakara (1979), the story of an innocent dimwit. Along with John Paul, another of Malayalam’s great screenwriters, he made memorable films like Chamaram, on the forbidden love affair between a college student and a lecturer, and Kathodu Kathoram. Bharathan’s magnum opus Vaishali, a visually stunning film that opened up new interpretations of the mythic tale of Rishyashringa, came as a result of his partnership with legendary writer M.T. Vasudevan Nair, who also wrote the screenplay for Thazhvaram, another classic that set a wild west story in a Kerala landscape.

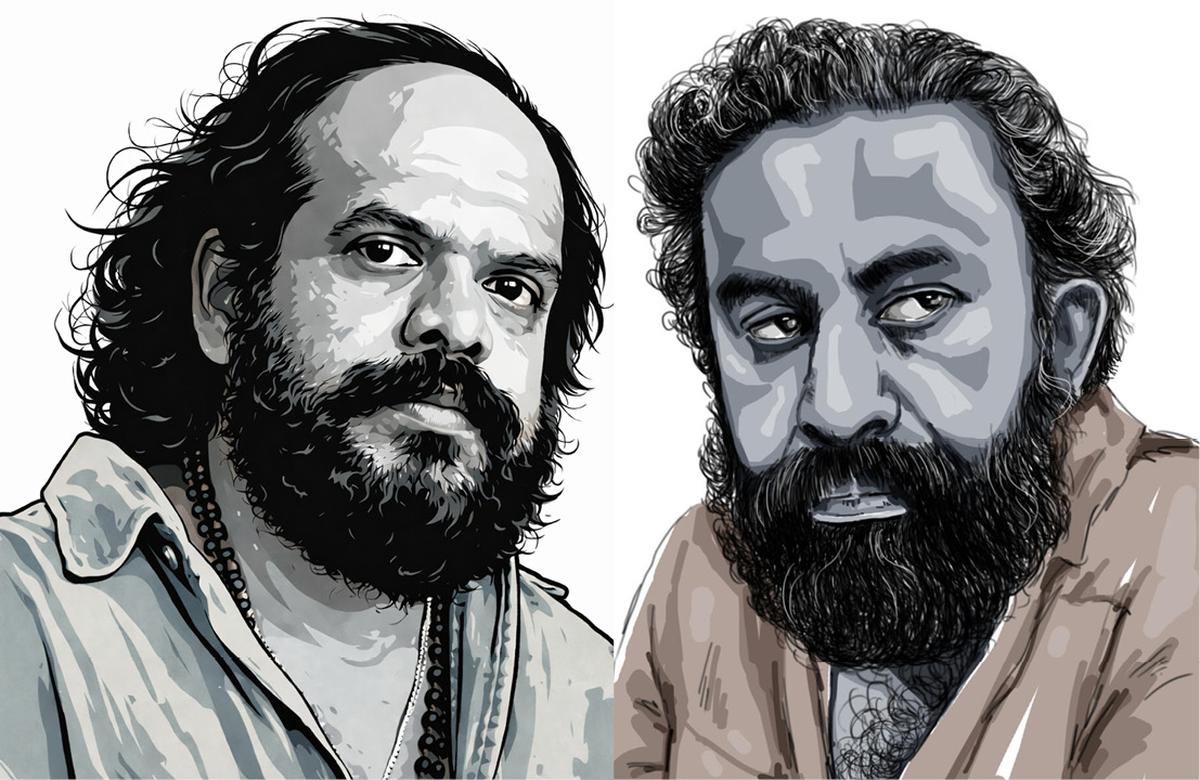

Filmmaker Bharathan (left) nudged literary star Padmarajan (right) into cinema; Padmarajan emerged as a versatile auteur, later celebrated for bold narratives and enduring romantic classics.

| Photo Credit:

ChatGPT and Sreejith R.Kumar

In the early 1970s, M.T., who had already written some much-admired screenplays centred on joint families, made his filmmaking debut with Nirmalyam, which ended with a poverty-ridden oracle, defeated by all means in his life, spitting at an idol in sheer rage and disillusionment. M.T.’s partnership with Hariharan yielded grand epics such as Oru Vadakkan Veeragatha, which redeemed the folklore version of Chandu through a clever retelling, as well as sensitive portrayals of teenage life as in Nakhakshathangal (1986), Aranyakam (1988) and Ennu Swantham Janakikutty (1998), with Aranyakam having a strong political subtext too. Panchagni (1986) had as its protagonist a fiery woman Naxal leader out on parole, while Amrutham Gamaya (1987) had a guilt-ridden protagonist trying to make amends for a crime that he had committed in his youth. When M.T. teamed up with I.V. Sasi, he brought more depth to the works of one of Malayalam’s most commercially successful filmmakers. Together, they made films like Uyarangalil (1984), Aalkkoottathil Thaniye (1984), Adiyozhukkukal (1984) and Anubandham (1985), all of which are memorable for their strong characters and controlled drama.

M.T. Vasudevan Nair’s screenplays transformed Malayalam cinema. From his debut Nirmalyam to epics like Oru Vadakkan Veeragatha with Hariharan, his work brought depth, nuance, and memorable characters to films.

| Photo Credit:

S. Mahinsha

The 1980s also witnessed Malayalam cinema embracing technological advancements, with Jijo Punnoose directing the first indigenous 70mm film Padayottam (1982) and the first Indian movie to be filmed in 3D format, My Dear Kuttichathan (1984).

A scene from My Dear Kuttichathan (1984), the first Indian film to be shot in 3D format.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

A revitalised mainstream

This era of middle-of-the-road cinema with much more depth and an aesthetic bent compared to the average commercial potboiler in a way lifted the standard of mainstream cinema of this era too. The mainstream space witnessed the emergence of a bunch of screenwriters and filmmakers who were capable of mirroring the concerns of the average Malayali on screen while at the same time making them laugh along with it.

Sreenivasan’s screenwriting stints with filmmaker Sathyan Anthikkad yielded some of the memorable films of this genre, from Gandhinagar 2nd Street to Sanmanassullavarkku Samadhanam and T.P. Balagopalan M.A., all of which had humour tinged with despair. Siddique-Lal also mined humour from hopelessness and found box office gold in their debut Ramji Rao Speaking as well as subsequent ventures in their short-lived partnership.

It was Sreenivasan’s mastery of social satire and deadpan humour that set the tone for this era. As both a scenarist and an actor, he used self-deprecating humour to the hilt to hold a mirror up to society. While the two films he directed — Vadakkunokkiyanthram and Chithavishtayaya Shyamala — took sharp jibes at suspicious husbands and those shirking responsibility respectively, several of his screenplays, such as Sandesham, were political satires that at times drew criticism for promoting apolitical thought. Even his critics, however, were unanimous about his remarkable sense of humour.

Master of social satire and deadpan humour, Sreenivasan’s self-deprecating wit held a mirror to society through screenplays and performances.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

Amid this, there was Priyadarshan, who began his career making slapstick comedies that went on to become evergreen favourites with the Malayali audience. During this period in the 1980s and early 1990s, considered to be one of the golden periods of Malayalam cinema, the mainstream space was filled with filmmakers of such varied hues that the sheer variety of subjects and treatment was astounding. From Sibi Malayil and Lohithadas making deeply affecting films on the defeated and the misunderstood to Fazil making a string of sensitive dramas as well as the classic Manichithrathazhu, and Joshiy making larger-than-life action films, it was an eclectic mix.

Drawing the full advantage of the opportunity provided by this wellspring of brilliant screenwriters and filmmakers were two actors who even now, four decades later, continue to be major draws at the box office — Mohanlal and Mammootty. Holding their own, through the sheer force of their talent, amid the male-centred narratives were actresses like Urvashi, Shobhana, Seema and a few others. It was also a period when Malayalam had a wealth of character actors including Thilakan, Nedumudi Venu, Sukumari, KPAC Lalitha, Innocent, Jagathy, Oduvil Unnikrishnan, Mammukoya, Kalpana and others, who could easily slip into any role a writer could imagine.

An industry in shambles

Although the two stars remained major draws at the box office, superstardom came with other side effects, like the fixation with the mass hero avatar. By the late 1990s, many of the great screenwriters in Malayalam cinema had slowly faded out, and there was hardly anyone of matching depth to replace them. This was evident in the general deteriorating quality of the films from the industry in this period. After a bunch of successful commercial entertainers in which they played mass heroes, the superstars also slowly began to fall into a rut, with roles and films that could hardly be differentiated from each other. Malayalam mainstream cinema in the early 2000s was marked by hypermasculinity and ingrained misogyny. Vocal and self-confident women almost always ended up being portrayed negatively in this world.

The slow revival

Shyamaprasad’s Ritu (2009), one of the early signs of change in the industry, was ironically about a group of people who were all struggling to cope with the changes in their lives. The real signal that the industry was turning a corner came two years later with Rajesh Pillai’s Traffic (2011). Borrowing the hyperlink format of screenwriting, made popular by filmmakers like Alejandro González Iñárritu, it told the story of a brain-dead youngster’s heart being transported to a hospital in another district, about 150 kilometres away. The huge box office success of that film spurred many aspiring filmmakers to try out new ways of telling their stories and also gave the much-needed confidence to producers to invest in fresh ideas.

One of those who had set their minds on rewriting some of the long-worn-out tropes was Syam Pushkaran, who debuted with Salt N’ Pepper (2011), co-written with Dileesh Nair and directed by Aashiq Abu. For Maheshinte Prathikaram, the remarkable directorial debut of Dileesh Pothan, he gave a light-hearted twist to the revenge drama, which used to be a show of masculinity in umpteen films. He went a step further in Kumbalangi Nights, directed by Madhu C. Narayanan, by turning a ‘complete man’ drunk on toxicity into a laughing stock.

The screenwriters of this past decade have also been careful in writing women characters with voice and agency, instead of relegating them as mere onlookers or secret admirers of the heroism of men. Films with a clear feminist perspective like Jeo Baby’s The Great Indian Kitchen (2021), which captured the drudgery and oppression in a woman’s daily life, and Vipin Das’s Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hey (2022), on a woman’s fightback against domestic violence, were not only made but also garnered wide appreciation. It has culminated this year in Lokah Chapter 1: Chandra, starring Kalyani Priyadarshan, the first female superhero film made in India, with a clever blend of Kerala folklore and familiar superhero tropes.

Fahadh Faasil in Maheshinte Prathikaram. Dileesh Pothan’s directorial debut offered a light-hearted twist to the revenge drama, subverting the genre’s typical masculine posturing.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

WCC and the Hema Committee report

The course correction within Malayalam cinema was also dictated by external events. The abduction and sexual assault of a popular woman actor on the night of February 17, 2017, allegedly by a gang contracted by actor Dileep, shook the industry. The outrage and the debates that followed the assault led to the formation of the Women in Cinema Collective (WCC), based on whose demand the Kerala government constituted the Justice K. Hema Committee to study the various issues in the industry, including those faced by women. The report was released in August 2024, revealing shocking tales of exploitation, sexual harassment, illegal bans and inhuman working conditions. In the intervening years after the formation of the WCC, Kerala’s public sphere has witnessed heated debates on the ingrained misogyny in Malayalam cinema, which has clearly led many to rethink, going by the relative absence of such things in films these days.

A trial court acquitted Dileep in the case on December 8, 2025 citing lack of evidence for conspiracy, even as six others were convicted. The State government has indicated that it will file an appeal.

Malayalam mainstream cinema in the post-liberalisation era also did not pay much attention to the margins of society or take care to look at what was happening to the majority through a socio-political lens. Also, for a State with such a variety of dialects, the characters in many films usually spoke a ‘Valluvanadan’ accent. However, with a push towards more authentic portrayals over the past decade, the dialects from almost every corner of Kerala can be heard in Malayalam movies now, be it the ‘Made in Kanhangad’ films of Senna Hegde or the Malappuram flavour of Thallumala.

In the films of the likes of Rajeev Ravi, the marginalised often found representation and a voice. With his unique films set in raw, chaotic spaces, Lijo Jose Pellissery has also made a mark as one of the master filmmakers of the present era in Malayalam.

Finding a new audience

Independent films from Kerala have always made their mark outside the State and garnered praise at international film festivals. However, for Malayalam mainstream films to find their audience among non-Malayalis, a lot of things had to come together. Except for independent films, most Malayalam films did not have proper English subtitles until about 2012. Even now, some of the classics from yesteryears remain unknown outside the State due to this.

Some of the first films to release with English subtitles were Jeethu Joseph’s Drishyam (2013), Anjali Menon’s Bangalore Days (2014) and Alphonse Puthren’s Premam (2015), all of which soon found large audiences outside Kerala. The new set of audiences who were pulled in by these films went on to explore further, thus aiding in building the chatter about the wonders of the Malayalam industry outside the State. The arrival of OTT platforms in the post-COVID-19 days further expanded the market, especially with films like Mahesh Narayanan’s C U Soon (2020), a film told only through screens. Malayalam cinema’s fortunes changed further with the trend in recent years to release films in Europe, the U.S., West Asia and other centres on the same day. This was one of the factors that led to films in recent years breaching the ₹100 crore and ₹200 crore marks, which are much beyond the reach of the domestic market.

Survival thriller Manjummel Boys made history as the first Malayalam film to cross ₹200 crore at the global box office.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

The current phase of Malayalam cinema, when it is expanding its geographical reach, is happening at the same time as ‘pan-Indian films’ with massive budgets. But the films from Malayalam that have garnered attention nationally have all been made on a limited budget. This has been the case with the superhero film Lokah Chapter 1: Chandra, reportedly made on a ₹30 crore budget, which is small for a film of that scale, or the survival thriller Manjummel Boys.

Among the filmmakers making waves in the Malayalam film industry currently are those who grew up watching world cinema and independent cinema at the International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK), a festival that became a reality in the late 1990s due to the efforts of the people behind Kerala’s strong film society movement. No genre is currently anathema in the Malayalam industry. Going by the number of debutant filmmakers with exciting ideas and a new set of actors who have endeared themselves to the masses, the spring in Malayalam cinema has only begun.

This article is part of The Hindu e-book. Kerala: a model State’s paradox

Published – February 20, 2026 01:52 pm IST

Email

SEE ALL

Remove