Scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and other universities are analyzing tiny particles from a distant asteroid to learn more about how the outer solar system was formed and shaped more than 4.6 billion years ago.

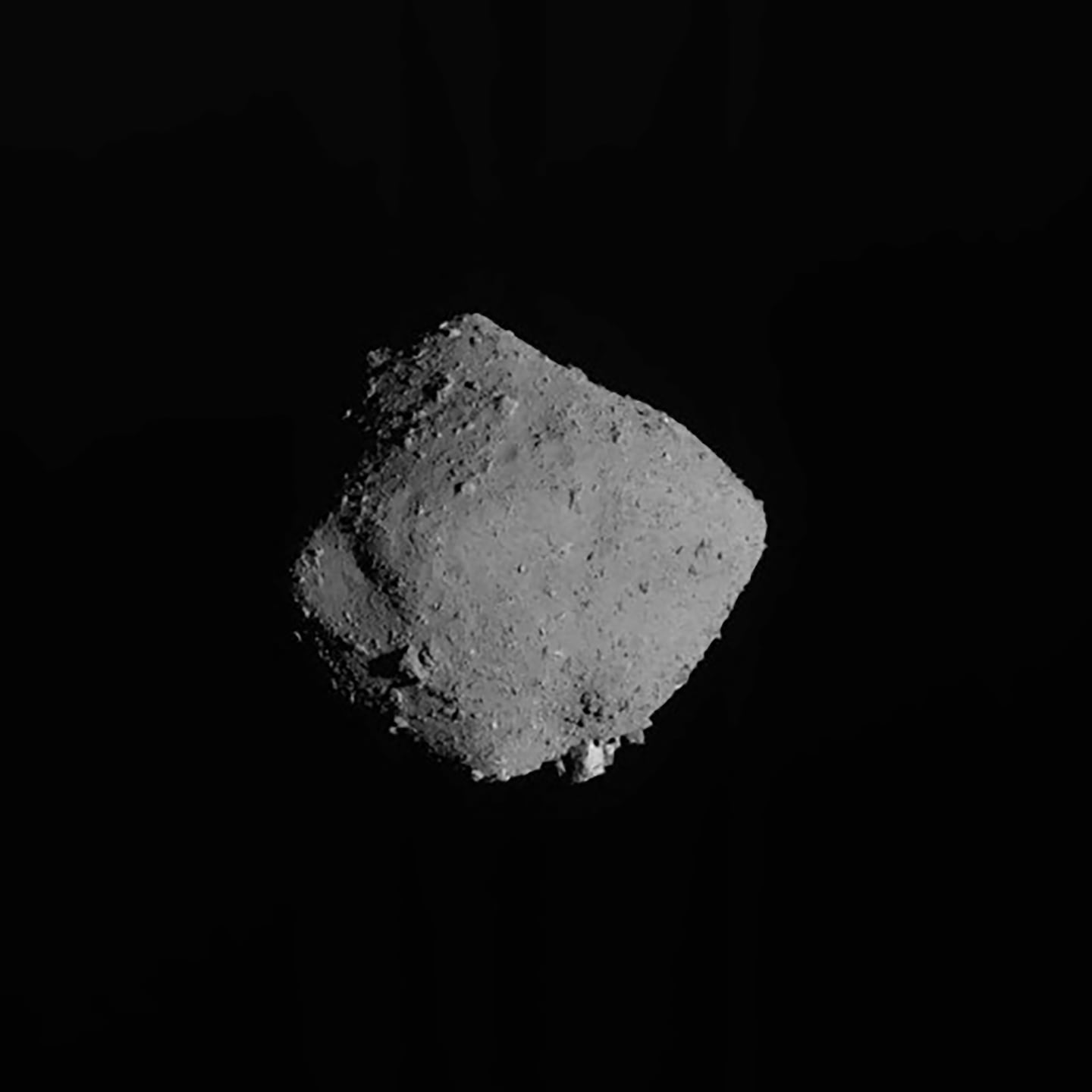

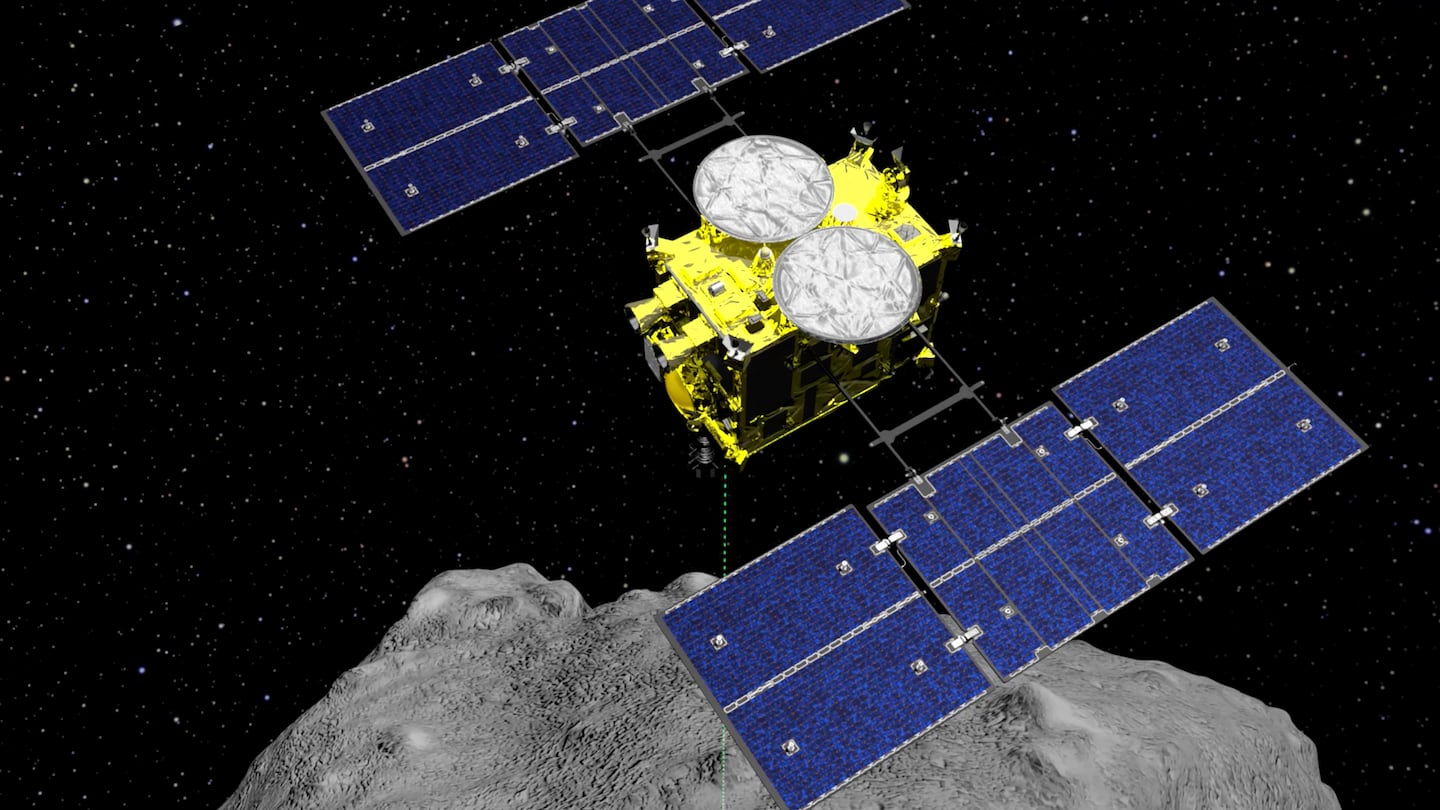

After analyzing particles of asteroid Ryugu, brought to Earth in 2020 by the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Hayabusa2 mission, scientists determined that an ancient magnetic field may have formed the outer solar system’s giant planets, from Jupiter to Neptune, MIT researchers said.

“We’re showing that, everywhere we look now, there was some sort of magnetic field that was responsible for bringing mass to where the sun and planets were forming,” Benjamin Weiss, MIT’s Robert R. Shrock professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences, said in a statement. “That now applies to the outer solar system planets.”

Their research revealed that a weak magnetic field likely existed when the asteroid first took shape, researchers said. At most, the field would have been merely 15 microtesla — a unit of measurement for the strength of magnetic fields — compared with Earth’s magnetic field of 50 microtesla.

But even that “low-grade field intensity” would have had the power to pull together primordial gas and dust to help form the outer system’s celestial bodies, from asteroids to planets, researchers said.

“When you’re further from the sun, a weak magnetic field goes a long way,” Weiss said in a statement. “It was predicted that it doesn’t need to be that strong out there, and that’s what we’re seeing.”

While scientists have known that a magnetic field shaped the inner solar system, where Earth and the terrestrial planets were formed, it was unclear whether “such a magnetic influence extended into more remote regions, until now,” researchers said.

Researchers also say analyses like this are the only way to study the presence of magnetic fields.

“Astronomical observations can’t detect those fields so really this is the only game in town right now for seeing whether it’s there,” Weiss said in an interview Thursday.

The researchers placed several particles, each about a millimeter in size, in a magnetometer to measure the strength and direction of their magnetization, researchers said. They later applied an alternating magnetic field to gradually demagnetize each sample.

The samples had no clear sign of a preserved magnetic field, suggesting there was either no “field present in the outer solar system where the asteroid first formed or it or the field was so weak that it was not recorded in the asteroid’s grains,” the statement said.

Despite these discoveries, information on magnetic fields in the outer solar system is still limited.

“How far this magnetic field extended, and what role it played in more distal regions, is still uncertain because there haven’t been many samples that could tell us about the outer solar system,” said Elias Mansbach, the study’s lead author and a postdoctoral researcher at Cambridge University.

Scientists believe Ryugu formed on the outskirts of the early solar system before migrating inward and eventually settling into orbit between Earth and Mars, researchers said.

“What’s special about Ryugu… is that [it seems] to be recording a field really far out beyond the giant planets,” Weiss said in the interview. To understand how the material that formed giant planets flowed inward, “you can test the idea that a magnetic field did this by looking for a record as a fossil in these ancient rocky materials,” he said.

Around 4.6 billion years ago, the sun formed through a dense cloud of gas and dust that collapsed into a swirling disk of matter, researchers said. The sun and remaining ionized gas created a magnetic field that pulled matter in to form planets, asteroids, and moons.

“How the mass flowed inward to make the sun and planets has been a fundamental question in astrophysics for decades,” Weiss said. “Theories long suggest that a magnetic field did this.”

Researchers also announced plans to look for more evidence of distal magnetic fields in another asteroid, Bennu, delivered to Earth in September 2023 by NASA’s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft.

Experts say this research could expand beyond asteroids.

“An exciting thing that’s probably going to happen in the next maybe few decades… is that we’re going to start bringing samples back from comets,” Weiss said.

Sabrina Lam can be reached at [email protected].

This post was originally published on here