Article begins

In January of 2021, I was employed as a postdoctoral researcher in a division of public health at a medical school. This provided early access to the COVID-19 vaccine. Although there was great discussion of the ethics of receiving vaccines in the early part of the vaccine roll-out, I opted to get the vaccine once it was available for all hospital employees, after prioritizing front-line healthcare workers, the elderly, and other vulnerable groups. Vaccine side effects (very sore arm, fatigue, fever) were well-publicized, but the intensity and duration of these experiences (How sore of an arm? How fatigued? How high of a fever? How long did these effects last?) were greatly debated as many of us worked from home and waited for access to the vaccines that would provide protection from severe illness and death. I happened to get my vaccine on Jan 26th, the same day that a friend across the country (who did some caregiving for her elderly mother) received the vaccine, and we texted each other about our side effects. Yes, my arm hurts, does yours? Yes, I’m tired, are you? (Fig. 1) Then, on a video chat, complaints from both of us about periods. This sparked my interest as it dovetailed with my ongoing research about factors that influence menstrual cycles, such as energetic stress or immune stress.

Credit:

Katharine Lee

Figure 1: Screenshot of texts between the author and an unnamed friend

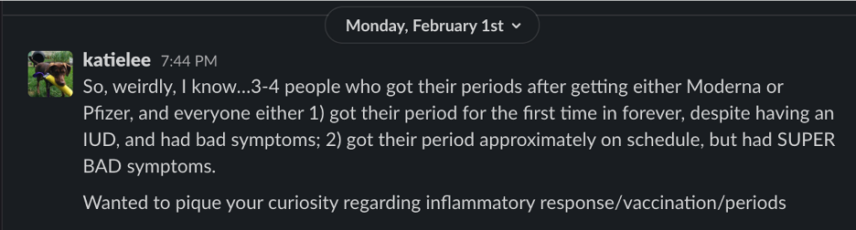

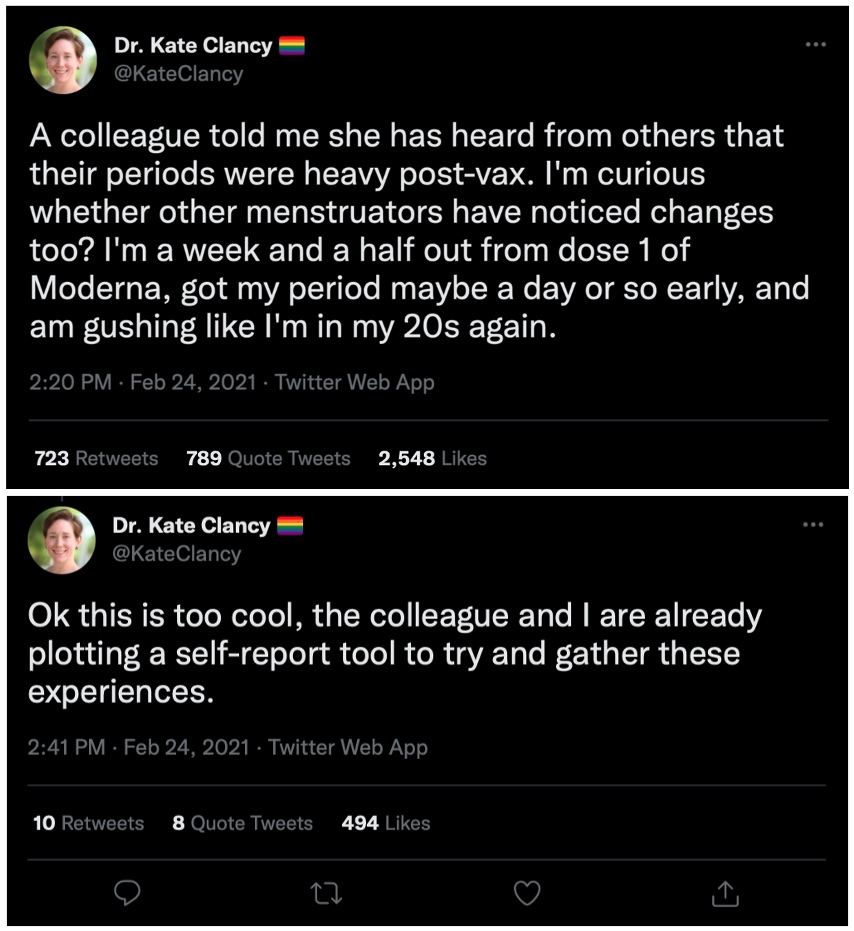

As a casual follow-up, I expanded my inquiry to colleagues, friends, and others I knew—anyone who got an early vaccine and menstruated—to see if they noticed anything with their periods. Then I reached out to Kate Clancy (my collaborator for the project that developed, and the chair of my dissertation committee shortly before) to ask if she knew anything about periods and vaccines, or if anyone had mentioned this to her. As a period researcher, people often tell you unsolicited personal information like this. On February 1 when I asked (Fig. 2), she hadn’t heard anything. Later that month, however, she was eligible for the vaccine and, after receiving it, also noted changes to her period. She posted about it on Twitter (Fig. 3), and immediately received numerous responses. As we chatted on Slack about the comments her post received, we said someone should look into this. And then, a few minutes later, we realized we were just as good as anyone else to start an inquiry into this topic.

Feminist science and feminist data practices grapple with issues of power, noticing, ignorance, situated knowledge, positionality, reflexivity, and more. While our questions were based on deep engagement with academic literature on menstruation, we did not only want data that we could sort and categorize into preconceived, pseudo-objective, quantifiable categories. We wanted to link biology with the novel lived experiences we were hearing. While many assume discussions of menstruation are taboo, the immediate and public response to Kate’s simple query highlighted a deep desire to share and understand personal experiences. The knowledge gaps around menstruation (broadly speaking) and the dearth of any official discourse or guidance on the idea of vaccines influencing menstrual bleeding contrasted with the intensity and volume of stories that were piling up on social media and our email inboxes. As part of our feminist praxis, we wanted to listen and learn from a broad swath of experiences of post-vaccine menstrual or uterine bleeding experiences in order to detect emerging trends and frame our next questions. We decided to use our existing biological knowledge to frame specific questions in combination with open-ended questions to collect and aggregate the stories.

Much as Michelle Murphy described the use of surveys to characterize unwellness of women in office buildings, we were hoping “to capture a phenomenon that was nonspecific and only discernable in a cluster, not an individual.” We intentionally wrote our survey to be gender inclusive, to be applicable to people who have menstrual disorders (e.g., endometriosis, polycystic ovarian syndrome, fibroids), and to allow participation from people who do not currently menstruate (due to gender-affirming hormones, menstrual-suppressing long-acting reversible contraceptives, menopause, and so on). After revising the survey, we submitted it for IRB approval from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and in April launched what we expected to be a small (maybe 500-1,000 participants) study. We did not expect this project, which we would nickname “PdVax” or “BLEEDVax” (Biomarkers and Lived Experiences with Endometrial Dysregulation from the SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines), to go viral on social media, or for it to circulate so broadly on Twitter, Tumblr, and Instagram, as well as percolate through many private Discord, Facebook, and other platforms.

Credit:

Katharine Lee

Figure 2: Screenshot of Slack message, from February 1, 2021

Credit:

Kate Clancy

Figure 3: Screenshots of posts from Kate Clancy’s Twitter asking about periods after vaccines (Fig. 3a, from February 24, 2021, at 2:20 p.m.), then commenting that we were starting to think about how to gather these experiences (Fig. 3b, from February 24, 2021, at 2:41 p.m.). These screenshots were taken in 2023.

From the time Kate Clancy tweeted about her experience and well beyond the launch of the survey, discussion continued on Twitter and other social media spaces. Amidst these continuing conversations, the survey launched in early April 2021, alongside multiple news media articles about the topic. Much of the traditional media coverage also included comments from medical professionals, such as MDs, stating things like “there is currently no scientific evidence proving that the vaccines cause heavier or irregular periods”; “there’s no plausible biological mechanism by which this would occur”; and “I think that there’s really no biological mechanism that is plausible in terms of how that could be possible…I think that potentially people are having normal menstrual pain plus the aches and pains that are associated post-vaccine, and maybe combining all of that together and associating it.” There was a trend in news coverage of this project which minimized our disciplinary expertise (human biologists and anthropologists who study menstruation), while elevating the dismissive commentary of many MDs who were not specialists in menstruation. There is a plethora of research showing how immune, inflammatory, energetic, and psychosocial stress can influence menstruation, and we describe some of it in our 2022 publication. But menstrual variability, like many other forms of human variation, is often ignored when biomedicine focuses on biased conceptions of “normal” human biology.

Echoing other times when women have mobilized to draw attention to an overlooked health issue, some blamed menstrual changes on “the stress of the entire year… The pandemic, and the political and social justice pieces, that I think have really affected people.” Specific physiological processes cannot yet explain the link between “stress” and menstrual changes, but these discussions and dismissals were not new. Feminists and gynecological health advocates have wrestled with the concept and mobilization of “stress” as a non-specific cause that could both be used to dismiss concerns (“just stress”) or be used to mobilize activists to change the world in ways that improve our lives (as Murphypoints out: “stress was a biological reaction to social conditions”).

Credit:

Tumblr user blinddoglee

Due to continued news media attention and social media attention, pressure from the public spurred the National Institute of Health (NIH) to allocate funds to research this topic. Standard NIH grant applications take months to a year between the proposal submission and receipt of funding. Structural and programmatic realities of NIH funding paradigms caused this funding to be released as what is known as an “Administrative Supplement,” meaning additional funds could be more quickly dispersed to researchers who already held an appropriate type of NIH grant on a related topic. Here, the NIH was able to announce funding awards to five research groups (not ours) by late August of 2021, and the first publications out of this funding began to emerge in 2022 and 2023, though not all publications resulting from this funding were about vaccines. We also published our first peer-reviewed results in 2022 after sharing it as a pre-print (a citable form of the paper, prior to peer-review) in 2021 and updating it in 2022. Overall, most studies using a variety of research designs and different datasets looking into changes in menstrual bleeding after vaccines have found some changes to menstrual cycles, which may occur in cycle length, bleeding intensity, or other unexpected symptomology. Most of these changes fall below the clinical thresholds for diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding; however, these changes can and do cause concern for many people.

Thanks at least in part to the attention garnered through our research and the uptake of the project by engaged participants and social media, recognition of menstrual changes after vaccines has moved from dismissal and gaslighting into established canon and accepted reality for many in biomedical, clinical, and public spaces. Although research on physiological and cellular processes causing these menstrual disruptions is still lacking, the evidence for an effect was strong enough that in fall 2022 the EU added heavy menstrual bleeding as a possible side effect from mRNA vaccines.Anthropological praxis, feminist science, and feminist communities can and do change the world. All subdisciplines of anthropology recognize the importance of contextualizing events, creating a discipline that respects paying attention while withholding judgment and remaining flexible during research. Our story shows the value of leveraging reflexive and iterative methodologies while conducting research on rapidly developing topics. We began by paying attention, believing people when they shared their experiences, centering research around these experiences, and building trust. News of our project moved through networked communities like Twitter, Tumblr, Discord, Instagram, and Facebook, eventually shaping biomedical discourse, shifting funding to answer questions that others dismissed, and highlighting an overlooked and emergent phenomenon. We thank everyone who participated or spread the word about this research, even the haters. As a Tumblr user wrote about this phenomenon and our study, “Let the vagina have a monologue.” We will continue listening.

This post was originally published on here