The discovery indicates a greater diversity in the fossil record of flowering plants than was previously acknowledged.

In 1969, fossilized leaves of Othniophyton elongatum—a name meaning “alien plant”—were discovered in eastern Utah. Initially, scientists speculated that this extinct species might have been part of the ginseng family (Araliaceae). However, this assumption is now being reconsidered as new fossil specimens suggest that Othniophyton elongatum is even stranger than previously believed.

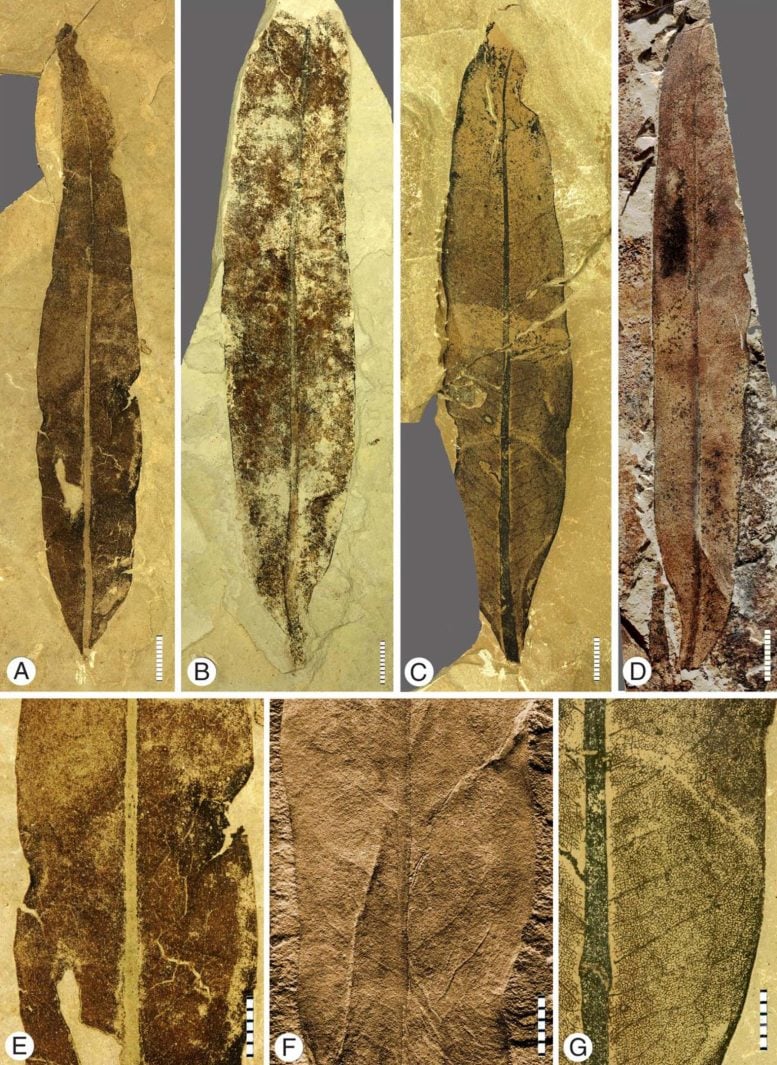

Steven Manchester, curator of paleobotany at the Florida Museum of Natural History, has spent years studying 47-million-year-old fossils from Utah. During a visit to the paleobotany collection at the University of California, Berkeley, he encountered an exceptionally well-preserved and unidentified plant fossil. It had been collected from the same region where the Othniophyton elongatum leaves were originally found.

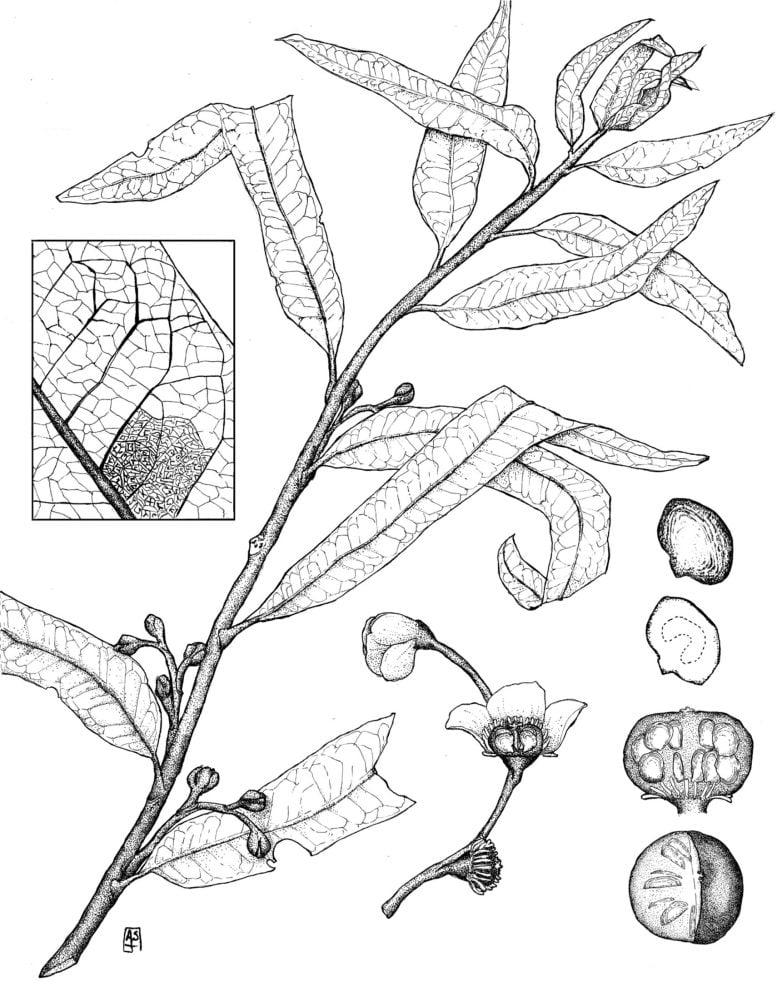

In a new study published in the journal Annals of Botany, Manchester and his colleagues demonstrated that the fossils, including the leaves examined in 1969, belong to a unique plant with distinctive flowers and fruits. Careful analysis confirmed that the fossils from 1969 and the Berkeley collection represent the same species. However, the leaves, fruits, and flowers attached to the woody stem in the Berkeley specimens were unlike anything seen in other plants of the ginseng family, to which Othniophyton elongatum was initially assigned.

“This fossil is rare in having the twig with attached fruits and leaves. Usually, those are found separately,” Manchester said.

The authors extensively analyzed physical features of the old and new fossils, then methodically searched for any living plant family to which they could belong. There are over 400 diverse families of flowering plants alive today, but the authors couldn’t match the fossils’ strange assortment of features with any of them.

Resisting the urge to tidily lump the obscure specimen in with a living group, the team then searched for extinct families it might have belonged to but came up empty-handed once again.

The authors say their results underscore what may be a pervasive problem in paleobotany. In many cases, extinct plants that existed less than 65 million years ago are placed within modern families, or genera — the taxonomic groups directly above the level of individual species. This can create a skewed estimate of biodiversity in ancient ecosystems.

“There are many things for which we have good evidence to put in a modern family or genus, but you can’t always shoehorn these things,” Manchester said.

The species does not belong to any living family or genus

The fossils were discovered in the Green River Formation near the ghost town of Rainbow in eastern Utah. Roughly 47 million years ago, the area was a tectonically active, massive inland lake system that provided the perfect conditions for fossil preservation. Low-oxygen lake sediments and showers of volcanic ash slowed the decomposition of many fish, reptiles, birds, invertebrates, and plants, allowing some of them to be preserved in amazing detail.

Researchers who had studied the original leaf fossils of this species had very little to work with. Without flowers, fruits or branches, they were limited to analyzing the shape and vein patterns of the leaves. Based on the arrangement, researchers thought it might be a single leaf made up of multiple smaller leaflets. This type of compound leaf is a defining feature of several plants in the ginseng family.

But the new fossils had leaves that were directly attached to stems, which painted a very different picture of what the plant once looked like.

“The two twigs we found show the same kind of leaf attached, but they’re not compound. They’re simple, which eliminates the possibility of it being anything in that family,” Manchester said.

The fossil’s berries ruled out families like the grasses and magnolias. The flowers did resemble some modern groups, but other features ruled those out, too. Even with such a pristine fossil in their repertoire, researchers were left with more questions than before.

Researchers could now see the fossil in a new light

Stumped, the team set the fossil aside for several years. Then the Florida Museum hired a curator of artificial intelligence who established a new microscopy workstation. When viewed through the digital microscope’s powerful lens and computer-enhanced shadow effect illumination, the authors could see subtle peculiarities they’d missed during prior observations.

When they focused on the fossil’s minute fruits, they could see micro-impressions left behind by their internal anatomy, including features of the small, developing seeds.

“Normally we don’t expect to see that preserved in these types of fossils, but maybe we’ve been overlooking it because our equipment didn’t pick up that kind of topographic relief,” Manchester said.

One of the plant’s strangest newly seen features was its stamens, the male reproductive organs of the flower. In most plant species, once the flower is fertilized, the stamens detach along with petals and the rest of the flower parts, which are no longer needed for reproduction.

“Usually, stamens will fall away as the fruit develops. And this thing seems unusual in that it’s retaining the stamens at the time it has mature fruits with seeds ready to disperse. We haven’t seen that in anything modern,” Manchester said.

With all modern families ruled out, they compared the traits to extinct families. Once again, there was no match to be found.

Julian Correa-Narvaez, the lead author of the study and a doctoral student at the University of Florida, played a major role in gathering information to identify the fossils. “It’s important because it gives us a little bit of a clue about how these organisms were evolving and adapting in different places,” he said.

Plant families can contain astonishing amounts of diversity. Seemingly disparate plants like poison ivy, cashews, and mangoes are all in the same family, along with over 800 other species. It’s unclear how much diversity in this mysterious extinct group has been lost to time.

This isn’t the only enigmatic species that has come out of the Green River Formation. Similar situations have unfolded when plant fossils from the locality surprised researchers, leading to the discovery of other extinct groups. “The book published in 1969 has all these interesting mysteries that remain,” Manchester said.

With digital access to museum specimens through tools like iDigBio, researchers can continue to study and understand the natural history of plant evolution.

Reference: “Vegetative and reproductive morphology of Othniophyton elongatum (MacGinitie) gen. et comb. nov., an extinct angiosperm of possible caryophyllalean affinity from the Eocene of Colorado and Utah, USA” by Steven R Manchester, Walter S Judd and Julian E Correa-Narvaez, 9 November 2024, Annals of Botany.

DOI: 10.1093/aob/mcae196

Walter Judd of the Florida Museum of Natural History is also a co-author of the study.

This post was originally published on here