By ITV News Producer Hannah Ward-Glenton

Teams across the world are learning about the pregnancy process to solve a number of medical challenges, including specialist incubators – known as ‘artificial wombs’ – to try and help premature babies survive and have longer and healthier lives.

Premature birth is the leading cause of death in children under five worldwide, according to the World Health Organisation, while an estimated 13.4 million babies were born pre-term – before 37 weeks of gestation – in 2020.

Babies born before before 27 weeks are considered extremely premature, and will often need to spend weeks, if not months, in specialist care.

These babies are then more likely to have issues with breathing, temperature regulation, blood sugar levels and fighting infection.

While so-called artificial wombs are being developed to try and give those babies a better chance of survival, other teams are looking at the very early stages of pregnancy to better understand how to grow stem cells outside of the uterus.

So what are the technologies currently being developed, and when will we see them in day-to-day use?

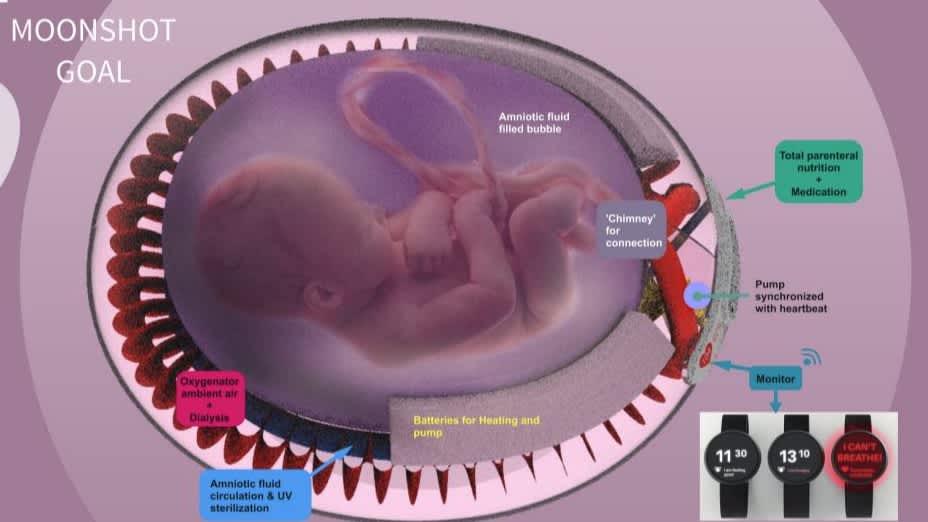

A liquid incubator

One team in the Netherlands is working on an incubator that will keep a foetus contained in the liquid sack it lives in while inside the womb. The invention would maintain the baby in that liquid state to prevent it from starting to breathe air, so that it can continue to develop as it would have in the womb.

Human testing with this kind of product isn’t a possibility, so it has to work first time, Professor Frans van de Vosse from the Eindhoven University of Technology told ITV News. Dolls designed to replicate mothers and babies have helped with this process so far.

“The kind of the first time you do, it would absolutely be in a real life case where, you know, there is a mother with her baby,” Professor van de Vosse said.

That first usage would likely be in an emergency scenario, where there is no other possibility that the baby would survive.

“The first use is in the situation which there’s no other way to save the baby… Because I cannot take the risk that the system is not functioning in a situation that another solution could be also a solution,” he said.

With such complicated – and controversial – technology, it isn’t just the machinery that needs to be developed.

Professor van de Vosse and his team have also considered how doctors would be trained to use their equipment, as well as developing a decision-making plan to help medical professionals along the way.

Even if the physical process of transferring a baby into the ‘artificial womb’ works, there are then other factors to consider to truly mimic a foetus’ experience in the womb, such as interactions with the mother.

Other elements such as how babies could receive the nutrients and medication that would naturally pass from mother to baby in the womb also pose their own challenges.

So when can we actually expect this kind of research to become reality in hospitals?

Professor van de Vosse said it could take some years, many years – or maybe it will never actually come to fruition. But that doesn’t mean the project isn’t worthwhile.

“We learn so much for the treatment for babies that even if we never develop a system that works, we learn so much… That is also a motivation for this work.”

“Science fiction, like the Matrix”

Other teams are working on developing a system that could be considered similar to an artificial womb, but they are not for growing babies – instead it is hoped it will help understand how to grow stem cells outside of the uterus.

The beauty of embryonic stem cells is they can become any type of cell in the body, which has huge potential for use across medicine.

“The whole field wants to make cells for transplantation, rejuvenation of tissue, diseases, alleviating, ageing, you name it,” developmental biologist at the Weizmann Institute of Science Professor Jacob Hanna said.

But mimicking the conditions to produce embryonic stems cells in the context of an embryo in a uterus is a huge challenge.

“Our goal was just to make a system and then use these systems and conditions to grow then stem cell derived embryo models to a lot of extents out of these,” Professor Hanna said.

Mouse embryos outside the uterus after five days, with a visible heartbeat, as recorded by Professor Hanna’s team

In 2021 Professor Hanna and his colleagues revealed a method for growing mouse embryos outside of a uterus than had ever been achieved before.

Like many others in his field, Hanna tends to avoid the term ‘artificial uterus’ – not necessarily because of the controversy around it, but because he doesn’t feel it properly captures his work.

He wanted to highlight that he isn’t seeking to create an artificial womb or growing babies in unnatural circumstances as an end goal – but his research in that area is helping him to learn about stem cells, which have myriad uses in healthcare.

“We want to make a system to grow embryos out of stem cells outside the uterus… It’s not the goal of like ‘let’s replace pregnancy’.”

The team have reached a point where they can almost take a mouse to a completed pregnancy.

“So just to say we grow from day five to day 11, we can now reach day 13. Mouse pregnancy is about 20 days…

“It’s like really watching a ball of cells that has no shape become an organ filled embryo. That anybody on the street would tell you, yes, this is an embryo.”

And it’s by creating what is essentially an ‘artificial womb’ that creates that environment and allows for that research to take place.

“The uterus is an excellent metabolic support machine,” Professor Hanna said.

With his research and other developments in the field, does Hanna feel like the concept of an ‘artificial womb’ can be realised anytime soon?

Not exactly.

“I think the human pregnancy… To do entire thing outside the uterus… I think it’s a very, very, very far fetched at the moment.

“The human embryo compared to the mouse is so big and the pregnancy is so long… I feel like we still have some major technological leap in order to do that as a field… I call it the Matrix, kind of like science fiction type of thing.”

Wearable wombs

While more human-like incubators may seem futuristic, other designs are looking to make the ‘artificial wombs’ even closer to the real thing.

Elisabeth Krenkler from the Berlin Institute of Health at Charite for example has been working on a design that would allow mothers who have given birth to premature babies to wear the technology holding their baby.

“Imagine you just had a baby and you are not able to hold it… You have to put it in a box, a glass box, and you will not be able to touch it for a very long time,” Ms Krenkler said at the Decoding the Future of Women Conference.

“I thought it was just a heartbreaking scenario so I thought there must be a better solution to empower the mother to be in charge again and to give the baby a more natural environment which is closer to the environment it was taken out of.”

Her design – which is very much in the early stages and would be a combination of the research of other scientists – would allow for the mother and baby to be much more physically connected than they would through an incubator.

“I wanted to bring the human-centred aspect in there to give the mother the opportunity to be closer to the baby … and in the best case have 24/7 closeness instead of the separation in the incubator,” she said.

The idea is that it would better simulate the experience of naturally carrying a baby to term than using an incubator.

Again in terms of when this kind of technology might be available in a hospital, Ms Krenkler says it’s a long time away.

“It’s still pretty far away from ever being in the hospital… It’s the future future,” she said.

Regulating artificial wombs

Development in the tech is exciting among the science and development spheres, but the process of testing the tech raises a lot of ethical and legal questions, Dr Chloe Romanis, an associate professor in biolaw at Durham University said.

Testing artificial wombs is not something that could be done in response to an emergency delivery of a premature baby, she said, but rather it would need to be premeditated.

Dr Romanis also highlighted that artificial wombs should not be presented as a “shiny miracle” cure to people who are delivering premature babies.

“That’s quite dangerous… It’s quite a big promise too, it’s a big risk. If this technology works, effectively it is undoing all of the risks and problems of being premature, and of the treatment associated with it,” she said, meaning it is crucial that information about the pros and cons are communicated to families in a nuanced way.

And the ethical dilemmas continue even if a product becomes fully functional and meets the huge number of regulatory standards needed for a medical device of this kind.

“How do we make sure everybody who needs this technology has access to it? Do we allow people to use it when … it’s not an urgent medical need?”

The Food and Drug Administration in the United States currently has an open public consultation asking people about their opinions on testing this kind of technology on humans.

‘Artificial wombs’ – a controversial name?

Even the name ‘artificial womb’ is controversial – and therefore is often avoided by people working in the field – as it suggests that scientists are attempting to recreate the pregnancy process, or possibly even replace it.

For some this then sparks the image of something similar to a baby factory, and for many groups, including various religious populations, that throws up issues around the idea of the sanctity of life.

In reality the term just means the recreation of conditions typically found in the womb – none of the scientists ITV News spoke to suggested at any point that these ‘artificial wombs’ would ever replace natural pregnancy.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country

This post was originally published on here