In the 1980’s sleep was for “wimps” and generally regarded as “an illness in need of a cure”. By the 2000’s sleep was starting to be taken seriously, and now, sleep has become a major preoccupation for many, and “getting the perfect night of sleep” an obsession.

Anxiety over our sleep has been fuelled by a stream of confusing information in the form of strident orders that resemble the commands of a Regimental Sergeant Major: You “must” get eight hours of sleep; Waking up in the middle of the night is “bad”; You “must” be up at 7am! Many sleep apps reinforce this anxiety with inaccurate information about the quality of our sleep.

Sleep anxiety has become a recognised condition where we worry about not falling asleep, and not being able to stay asleep. Such anxiety prevents sleep and this makes the anxiety worse. Triggering a cycle of worse sleep and increased anxiety!

Yes! – Sleep is an essential part of our biology and not getting the sleep we need can be seriously harmful. Short-term sleep loss will disrupt our memory, decision making, how we interact with others, and our emotions. Long-term sleep disruption, as experienced by shift workers, can result in serious illnesses including Type-2 diabetes, obesity, a less effective immune system, cardiovascular disease and even a greater risk of cancer. Yes – we need to prioritise our sleep, but “good sleep” is like shoe size, “one size does not fit all”. Whilst it is possible to make generalisations, taking an average value for sleep can be deeply misleading.

It’s worth stressing how variable normal sleep can be. So, between the ages of 18 to 64 years, most of us sleep between seven to nine hours each night, but some perfectly healthily individuals sleep six or even eleven hours. After 64, average sleep is between seven to eight hours, but the full range can be between nine to five hours.

Our ‘chronotype’, refers to whether we are a morning “lark” (wake around 5 am – 10% of the population), evening “owl” (would like to wake around 9 am – 25% of the population), or an in-between “dove” (wake around 7 am – 65% of the population). Our genetics play a role, but chronotype also changes with age. As teenagers and young adults, we tend to have later chronotypes, going to bed later, then move earlier in our middle and older years. On average, men tend to have a later chronotype compared to women.

We are often told that a single episode of sleep without waking (“monophasic” sleep) is normal. But it is not. Sleep can occur in two episodes (biphasic sleep) or even multiple episodes (polyphasic sleep), separated by short periods of wake, and this probably represents our ancestral pattern of sleep before artificial light. Critically, if we wake at night, sleep is likely to return if it is not sacrificed to social media or worrying about not getting back to sleep!

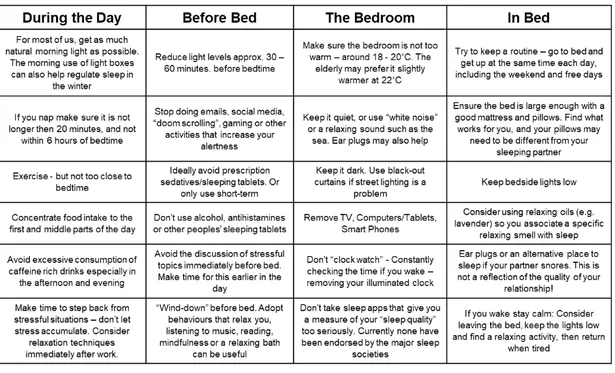

So how do we know if we are getting enough sleep? The answer is – “it depends”. But it’s not complicated. If you can function as you would like, and feel alert during the day, then you are fine. However, if you’re need an alarm clock to get you out of bed; if you oversleep on free days; if you take a long time to wake up; if you feel sleepy and irritable during the day and crave a nap; if you need caffeinated drinks (coffee, tea, cola) to keep you awake; and if you are more impulsive – this is all telling you that you are probably not getting enough sleep. Sleep does not have to be “what you get”, there is a lot that each of us can do about getting the sleep we want. Here are some suggestions based upon the scientific evidence. Above all use the sleep habits that work for you and stick to your routine:

The misinterpretation of scientific findings, and in some cases the need for a “good story”, has led to a quasi-epidemic of worry, anxiety, panic and stress about sleep. Recent books and reports have perpetuated the myth that there is only one sure-fire way of getting good sleep, and getting the “perfect night of sleep” has become an obsession for many. The key point is that sleep is highly variable and that we need to relax and embrace the sleep we get. Listening to your bodies rather than the avalanche of “one size fits all” misinformation cascading down upon us.

Professor Russell Foster is Director of the Sleep and Circadian Neuroscience Institute, University of Oxford and author of Life Time: The New Science of the Body Clock, and How It Can Revolutionize Your Sleep and Health, published in paperback by Penguin in 2023.

This post was originally published on here