A groundbreaking method reveals how the subatomic characteristics of titanium shape its physical properties.

A research team from Yokohama National University has developed a novel approach to investigate how the orientation and behavior of electrons in titanium affect its physical properties. Their findings, published in Communications Physics on December 18, 2024, offer valuable insights that could lead to the creation of more advanced and efficient titanium alloys.

Titanium is highly prized for its exceptional resistance to chemical corrosion, lightweight nature, and impressive strength-to-weight ratio. Its biocompatibility makes it an ideal material for medical applications such as implants, prosthetics, and artificial bones, while its strength and durability make it indispensable in aerospace engineering and precision manufacturing.

High Harmonic Generation: A New Approach

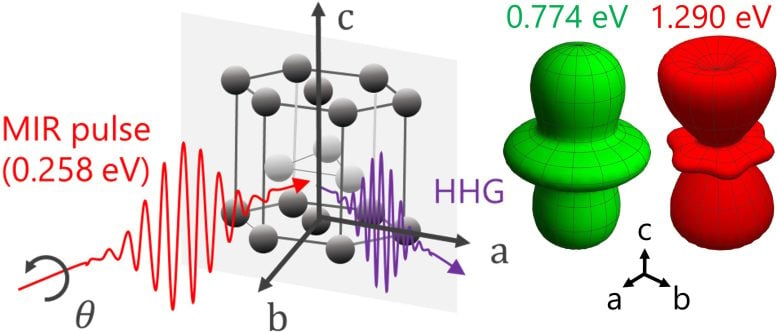

To get an idea of how titanium’s atoms and electrons generate these properties, the researchers used a process called high harmonic generation. “When we shine intense infrared laser pulses on a solid material, the electrons inside that material emit light signals at frequencies higher than that of the original laser beam,” explains the study’s first author, Professor Ikufumi Katayama of Yokohama National University’s Faculty of Engineering. “These signals help us study how the electrons behave and how the atoms are bonded.”

High harmonic generation is difficult with titanium and other metals, because the free electrons which make them excellent electrical conductors also interact strongly with the laser field and screen it in the material. This weakens the light signals, reducing their clarity and making it harder to collect data.

“We carefully tuned the laser settings to reduce the screening effect, allowing us to clearly observe how titanium’s electronic structure behaves,” says Katayama.

Analyzing Electron Behavior

The researchers used computer simulations to study the light signals emitted in response to the laser. They found that most of them came from electrons moving within certain zones called energy bands. These bands act like tracks where electrons can move freely. The direction of the laser and the way the titanium atoms are arranged affected how these electrons moved and bonded.

Titanium has a special uniaxial structure that can change with alloying, and its properties, like strength and flexibility, depend on the direction in which a force is applied. In other words, titanium behaves differently depending on the direction you push or pull on it. It turns out that this is because the way that the titanium atoms are arranged means the electrons don’t move the same way in all directions. When a laser hits titanium, the way the electrons absorb energy changes, affecting how they bond in different directions.

The researchers also found that fewer signals were emitted when electrons moved between different energy bands, showing that electron behavior is affected by the way atoms align. This difference determines whether the bonds are strong or weak, and thus how flexible or tough titanium is.

“By mapping how these bonds change with direction, we can understand why titanium has such unique mechanical properties,” says the study’s lead author, Dr. Tetsuya Matsunaga of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. “That helps us understand how to design stronger titanium alloys that work better under different conditions, which could help create stronger, more effective materials for industries like aviation, medicine, and manufacturing.”

Reference: “Three-dimensional bonding anisotropy of bulk hexagonal metal titanium demonstrated by high harmonic generation” by Ikufumi Katayama, Kento Uchida, Kimika Takashina, Akari Kishioka, Misa Kaiho, Satoshi Kusaba, Ryo Tamaki, Ken-ichi Shudo, Masahiro Kitajima, Thien Duc Ngo, Tadaaki Nagao, Jun Takeda, Koichiro Tanaka and Tetsuya Matsunaga, 18 December 2024, Communications Physics.

DOI: 10.1038/s42005-024-01906-0

The study was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the Research Center for Biomedical Engineering, the Light Metal Educational Foundation, and The Japan Institute of Metals and Materials.

This post was originally published on here