19/12/2023

11444 views

107 likes

In brief

ESA’s Gaia space telescope was launched on 19 December 2013 and has been surveying the skies since 2014. In this time, the mission has flipped our understanding of the Milky Way on its head, unveiling its shape and structure and revealing how mergers have affected the stars that call our galaxy home.

In-depth

Despite our many years spent observing the cosmos with ever-more powerful telescopes, there remains much to learn about the Milky Way. We cannot leave our galaxy to get a full outside view of its shape and properties, as we do when we study other galaxies. We are embedded within it, and so are limited to mapping the Milky Way from the inside out – and from a single vantage point.

At the start of the millennium, it became clear that in order to understand our galaxy’s intricacies we needed precise, comprehensive data, and a dedicated, highly advanced space mission to gather them. Enter Gaia. Since it began surveying the skies in 2014, the satellite has compiled an unrivalled dataset on the positions, distances and motions of around 1.5 billion stars, enabling researchers to dig deep into our galaxy’s past and current structure.

“Gaia’s discoveries represent a step change in how we understand the Milky Way. It’s astonishing what this mission has discovered in a relatively short space of time,” says Timo Prusti, Project Scientist for Gaia at ESA. “Gaia is uniquely designed to map the celestial objects around us. The mission is building a more detailed and complete view of the Milky Way, and this view is fundamentally changing what we thought we knew about our home galaxy.”

This overview features just some of the key discoveries Gaia has made in the past decade.

Weighing the Milky Way

Determining the mass of the Milky Way is a tricky business. There are multiple complex parts of the galaxy and multiple sophisticated ways to ‘weigh’ them, resulting in significant uncertainty.

The material in the Milky Way is spread out over a great area, extending far beyond the visible starry disc of the galaxy. This extended part of the Milky Way exists in the form of a so-called dark matter halo – a vast collection of material that appears to be dominated by invisible dark matter.

This halo is being studied in depth by Gaia, to understand how much dark matter lies there and how it is distributed through space. Scientists are using Gaia to explore objects within this halo, far from the Milky Way’s disc, including streams of stars and debris, star clusters and dwarf galaxies. Dwarf galaxies contain a few thousand to a few billion stars at most and over 50 of them orbit the Milky Way as satellites, with more being discovered every year. Since these objects lie so far away, we need Gaia’s precise observations to pin down their positions and motions (astrometry). In some cases, Gaia data is supplemented by targeted observations from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope.

These investigations have brought new insight about the dwarf galaxies orbiting the Milky Way, including one of the closest: the Large Magellanic Cloud. Gaia data has proven that this cloud is more massive than once thought, at about 10% of the mass of the Milky Way. Gaia has also shown how much this unexpectedly bulky galaxy influences the motions of objects further out in the Milky Way’s halo, skewing estimates of our galaxy’s mass that are derived by studying these satellite galaxies.

Our picture of the Milky Way gets better and better as Gaia returns more data. There are still large uncertainties surrounding its total mass, with estimates ranging from a few hundred billion to a few trillion times the mass of the Sun. But as Gaia continues to explore our cosmic home and its components, we’ll more fully understand the complicated distant parts of our galaxy.

Refining our galaxy’s shape

Gaia has clarified the appearance of our galaxy, providing a more accurate view of its shape and symmetry – or lack of it.

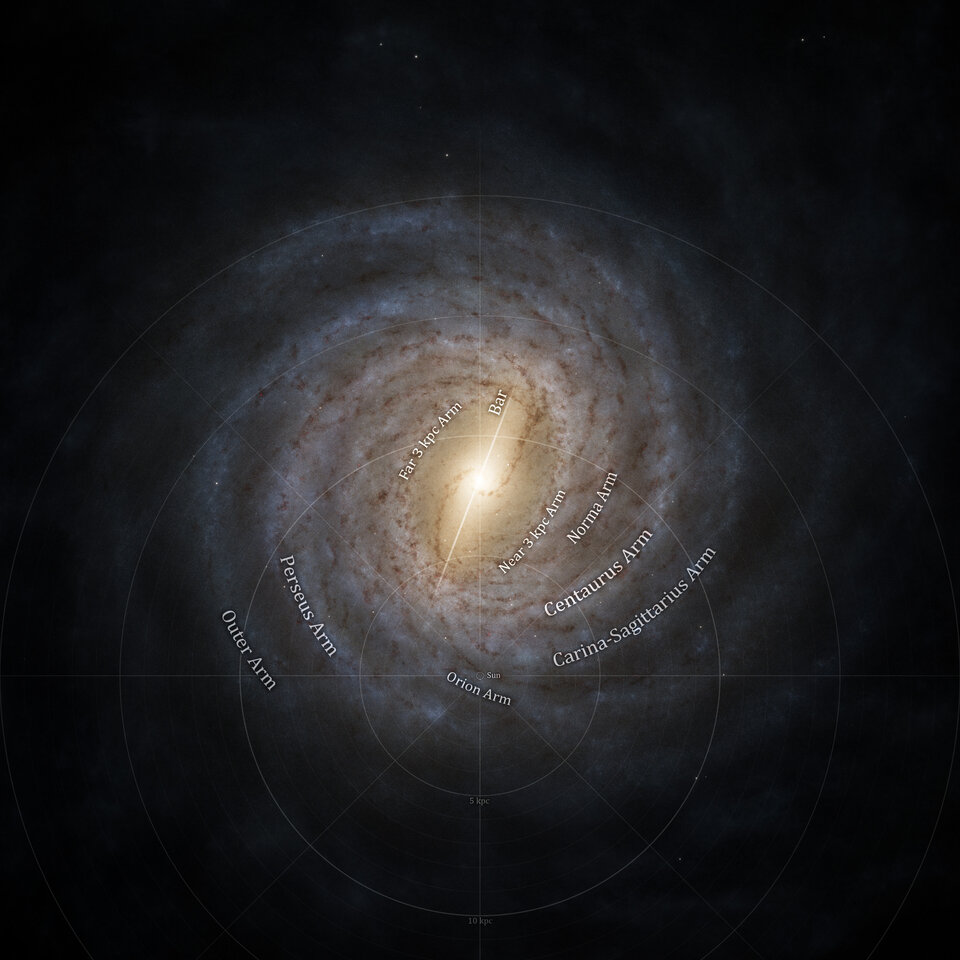

The Milky Way is a spiral galaxy with a central ‘bar’ of stars cutting through its core, multiple spiral arms, and a more diffuse halo extending outwards. This halo was assumed to be generally spherical and homogeneous, like a beach ball. However, Gaia has shown that the Milky Way’s halo instead looks elongated, tilted and stretched, like a rugby ball that has just been kicked.

Gaia scientists have also mapped the general structure of the Milky Way’s central bar and swirling spiral arms, refining our understanding of their length, tilt and asymmetry.

Additionally, we’ve known since the 1950s that the Milky Way’s disc is warped and asymmetrical, but we were unsure of why. Gaia has revealed that this warping is caused by an ongoing collision with another smaller galaxy – likely the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy, which has smashed through our galaxy’s disc three times in the past. Sagittarius has been orbiting our galaxy for 4–5 billion years, and is slowly being ripped apart in the course of an ongoing merger.

These collisions have sent disruptive waves and ripples spreading through the Milky Way like a stone thrown into water, causing the galaxy to warp and wobble. They may have been the trigger that caused the Sun and Solar System to form: another result from Gaia. According to Gaia, the ripples caused by the influence of Sagittarius prompted multiple bursts of new star formation, one of which aligns in time with when we believe the Sun to have formed some 4.6 billion years ago.

Gaia has shown that the Milky Way is still enduring some of the ripples caused by a near-miss collision with Sagittarius, which caused stars within the galaxy’s disc to move in distinct patterns. For some stars, Gaia measures not only their position in space but also their full movements in three dimensions. In these data, researchers have identified a never-before-seen pattern that looks a little like a snail’s shell. Further study led to the conclusion that the stars ‘remembered’ being perturbed by Sagittarius in the past, and still show signs of this in their ongoing motions.

Piecing together our family tree

Sagittarius is not the only galaxy to have influenced the Milky Way. The early history of our galaxy is turbulent; it began forming over 13 billion years ago and has grown bigger and more massive by merging with other galaxies over time. As galaxies are subsumed into the Milky Way, their material forms streams of stars moving through space along distinct trajectories; each stream characterised by distinctly different chemistries.

Gaia has revealed this ‘family tree’ of smaller galaxies that helped make the Milky Way what it is today. Crucially, Gaia discovered that the Milky Way merged with one galaxy, dubbed Gaia-Sausage-Enceladus, early in its formation – a major breakthrough in our understanding of galactic history. The 30 000 oddly moving stars that revealed this merger surround us almost completely; all move very differently to most of the other stars in the Milky Way, moving ‘in and out’ rather than ‘around’. The Milky Way and Gaia-Sausage-Enceladus merged some 10 billion years ago, and this event has significantly shaped the form and evolution of our galaxy since.

Gaia data also revealed another merger event, Arjuna/Sequoia/I’itoi, that likely happened at a similar stage to Gaia-Sausage-Enceladus. This event is thought to have filled the halo of the young Milky Way with globular clusters and ancient, high-velocity stars, all moving oddly and orbiting the ‘wrong’ way – in the direction opposite to the spiral’s spin. Arjuna/Sequoia/I’itoi and Gaia-Sausage-Enceladus may have been associated galaxies – perhaps a binary pair – before they merged with the Milky Way.

A subsequent Gaia study defined six distinct star groups, representing six different mergers: the aforementioned Sagittarius, Gaia-Sausage-Enceladus and Arjuna/Sequoia/I’itoi mergers, Cetus, LMS-1/Wukong, and Pontus. Most are thought to have taken place between eight and ten billion years ago, with only Sagittarius being more recent. Another study using Gaia data explored a population of globular star clusters and found these to align well to a predicted seventh merger. This merger would have been perhaps the earliest to occur around 11 billion years ago, with a galaxy now referred to as ‘Kraken’.

Additionally, Gaia has revealed that some parts of the Milky Way are far older than expected, and that there have been two key phases of galactic history. The first began under one billion years after the Big Bang, when stars began to form in a thick disc. Two billion years later a second phase of star formation was triggered here, as well as in the halo and thinner disc. This second phase is thought to have been sparked when the Gaia-Sausage-Enceladus collided with the Milky Way.

Gaia has also cast its eye over the smaller companion galaxies found in our patch of space today. These include the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, and tens of other dwarf galaxies thought to be orbiting the Milky Way. However, Gaia studied 40 of these companions and found them to be moving much faster than the giant stars and star clusters known to be orbiting our galaxy; this means they may instead be visitors that only arrived in our vicinity in the last few billion years.

Intriguing and surprising features

The Milky Way is filled with fascinating wavy structures made of gas, empty cavities in space, bursts of star formation, groups of star clusters whirling around the Milky Way’s core, odd neighbourhoods filled with ancient stars, and remnant signs of ‘fossilised’ spiral arms. All of these features, and others, have been detected and explored by Gaia.

In 2020, Gaia spotted the largest gaseous structure ever seen in our galaxy: a long, thin, undulating ensemble of interconnected stellar nurseries located in the spiral arm close to Earth. While this wave has existed for many millions of years, scientists needed Gaia data on the Milky Way’s 3D structure to find it and reveal its shape.

Gaia’s precise measurements of stars’ positions and motions have also revealed the shape and thickness of star-forming regions in three dimensions – the first time these so-called molecular clouds have been mapped in this way.

Further mapping uncovered the origin and impact of the Local Bubble, a relatively empty, peanut-shaped patch of space that the Sun traverses on its orbit through the Milky Way. We have known of the Local Bubble’s existence for some time, but Gaia has uncovered more. Gaia scientists found that a number of exploding stars pushed gas outwards to create this bubble, also triggering the formation of all the young stars we see in our galactic neighbourhood.

Looking further out in the Milky Way, scientists used Gaia data to map structures in our galaxy’s outer disc, revealing a huge number of spinning filaments. The scientists suggest that these filaments are actually the remnants of past spiral arms. These structures became excited over time as different satellite galaxies whirled past and interacted with our galaxy, causing them to spin.

Alongside structure, Gaia is keeping a close eye on stars. The mission has found thousands of new star clusters, many more than we knew of previously, thanks to scientists applying new machine learning techniques to Gaia data. In one key finding, astronomers used Gaia data to carry out ‘galactic archaeology’ and discover that the Milky Way’s core is full of stars that are truly ancient: so ancient that they lack the heavier metals created later in the Universe’s lifetime. Researchers identified these stars by exploring two million bright giant stars in our galaxy’s inner regions, mapping the Milky Way’s ‘poor old heart’.

The tip of the iceberg

These findings are just some of the ground-breaking results from Gaia. They, and others, have resulted in a renewed, clearer and more detailed view of the Milky Way’s structure, contents and history, giving us a far more complete understanding of our galaxy.

“As well as refining and demystifying some of the things we already knew, Gaia has questioned and ultimately rejected a number of assumptions we had about the Milky Way,” says Paul McMillan of University of Leicester. “It’s no exaggeration to say that Gaia is rewriting cosmic history.”

Gaia releases data in batches. The first, second, early-third and third of these came in 2016, 2018, 2020 and 2022 respectively, with a subsequent ‘focused product release’ earlier this year. This article focuses on discoveries made since Gaia’s early Data Release 3 in 2020 and reflects just a selection of the research coming from the mission. For more findings, see ESA’s Gaia page.

For more information, please contact:

ESA Media Relations

Email: [email protected]

This post was originally published on here