Do we still have a problem with racism? If you ask the average person even the most basic question about it – “Does racism still exist?” – half the population will say it doesn’t. According to a recent Guardian poll of British adults, more than half thought ethnic minorities faced less or the same discrimination as White people in most areas of life, such as the news, TV or films, the workplace, access to finance and jobs, and access to university or good schooling. Results in the US are similar. A 2021 Gallup poll revealed that slightly more than half of the White American population believe “racism against Black [people is] widespread in the US”. In the meantime, according to the same poll, slightly less than half of the White American population believe “racism against Whites [is] widespread in the US”. An earlier study (by Michael Norton and Samuel Sommers) showed that a growing number of White Americans believed “reverse racism”, or racism against White people, was the more prevalent form of racial bias.

This kind of division in our society is a massive problem to which those in positions of authority offer no clear answers. Politicians frequently pretend to be experts on a host of issues such as racism – and vaccines, and the climate crisis, and evolution – but they’re not. If they don’t have degrees or past careers in social psychology or climate science or evolutionary biology, then they are no more experts in the topic than you are and are as sharply divided as the rest of us.

Kim Johnson and Dawn Butler are both Black women, both Labour MPs and both of the opinion that the British police (and other institutions) are institutionally racist, as has been widely reported. This may have something to do with the fact that both women have been stopped and questioned by the police on what seemed to be very flimsy pretexts. In each case, once they identified themselves as members of parliament, the police quickly lost interest or even apologised, but both women believe racism was part of the reason why they were stopped and questioned. On the other side of the political aisle is the Conservative party leader, Kemi Badenoch, who, like Johnson and Butler, is Black and a woman, but not at all of the belief that institutional racism is a serious problem. She admits that there is some racism in the UK and that she has experienced some discrimination. But she strongly resists what she calls attempts to “politicise” her skin colour.

She has further claimed that many people who support critical race theory aren’t working towards any ideal future that we would recognise, but want reprehensible things such as a segregated society. Further still, Badenoch has stated that British teachers would be breaking the law if they taught their pupils about critical race theory and White privilege as if they were fact rather than merely one side’s political opinion. This is more than just talk. In 2021, the British government, after assembling a commission on race and ethnic disparities and conducting its own research, went on to publish the Sewell report, which found “no evidence of systemic or institutional racism” in the UK.

It’s hard to know what to believe. It’s hard to say which has more credibility: a peer-reviewed publication, a government report, a book? It’s hard to know which sources are reporting facts and which are just spouting opinions. And it’s often not clear who has the authority, expertise or methodology to back up their claims. Lots of very clever people with impressive-sounding degrees have published lots of books about racism that wildly disagree with each other and new books are published each year on either side of this heated, polarised debate. We have arguments in abundance. What we don’t seem to have in abundance are facts – or science.

Evidence is the coin of the realm in science. Not eloquence, not popularity, not even formal philosophical syllogisms, but evidence: the ability to make predictions about the real world that are more specific and more likely to come true than anyone else’s predictions.

And this means that in science, you can’t have wildly differing opinions on whether racism exists in society. Politicians can disagree on these things. Philosophers can disagree on these things. Pundits, activists, demagogues and professional debaters make their living out of disagreement. But by its nature, science tends towards consensus.

And what the continuing debate around racism ignores is that we have had a scientific consensus about it for a long time: there are decades worth of clear, factual, rigorous, quantitative scientific research out there that reveals empirical truths about racism: from its effects on friendships, relationships, healthcare and the criminal justice system to the financial cost of selling items online while Black.

Let’s look, for instance, at the question of how much less likely Black job applicants are to be called in for interview than White candidates.

Scientists Valentina Di Stasio and Anthony Heath conducted a study in 2019 applying for approximately 3,200 jobs in the UK using CVs that were identical except for the name of the person who was ostensibly applying for the post. They found that applicants with Black-sounding names (whether Nigerian, Ethiopian, Somalian or Ugandan) had a 12.3% callback rate. Despite their completely identical CVs, applicants with White, British-sounding names had a much more successful 24.1% callback rate: almost twice as high. Heath and Di Stasio went on to publish a meta-analysis of all the available field experiments on hiring discrimination against all ethnic minorities in the UK, so their final analysis included 43 comparisons between White, Black, south Asian and east Asian targets. However, if we focus on the different results for White and Black people, the authors say this: “The summary discrimination ratio is a substantial and highly significant 1:56 … In this series of studies, Black Caribbean applicants had to make about 50% more applications than their white British counterparts in order to receive a positive response.”

And this is what is meant by the scientific consensus. If you really searched, you could almost certainly find someone with some kind of scientific degree, or even someone with “professor” in front of their name, who would be willing to give their opinion that racism is not a factor in hiring decisions. If you’re very politically savvy, you could make sure that this person was an ethnic minority, making their opinion seem all the more credible.

However, you would not be able to find empirical experiments or meta-analyses that consistently show Black people and White people getting identical treatment for identical CVs. You would definitely not find studies consistently showing Black people getting favourable treatment over White people. Instead, you would consistently find experiments that show White people getting a distinct, significant advantage, even when all other explanations for that advantage are whittled away. That is how we know, scientifically, that racism is still a factor in hiring decisions, and that it has been a factor for a very long time.

A perpetually vexing aspect of the study of racism is the apparent lack of any actual racists. If racism is real, significant and empirically detectable, then why can’t we tell where it’s coming from? Who are the people doing all these racist things, and why can’t we identify them?

If you enter any company or speak to any search committee and ask them if they discriminate against ethnic minorities in their hiring practices, they will all (or nearly all) tell you that they don’t. Similarly, if you ask any teacher or educator if they discriminate against ethnic minority students, they’ll say that they don’t. And yet, when you hand them a hundred or a thousand pieces of equivalent work, they will rate the work by Black students as worse than the work by White students. If you ask any medical professional if she or he discriminates against ethnic minorities, you’re likely to get a stern dressing down and a request to leave the premises immediately. However, when you run the numbers, you’ll see that the ethnic minority appointments are scheduled to occur later than the ones for White people and that the ethnic minorities are less likely to be offered crucial life-saving treatments. So what’s going on?

Even if you ask people anonymously, you’ll still find that almost nobody thinks of themselves as a racist person. This is not a claim I make idly. In 2019, Keon West (that’s me) and Asia Eaton published interesting findings on just this topic. For our study, we asked 148 people to judge how racially egalitarian they were compared with people in the wider society and with other people in the room with them at the time. We gave them a rating scale of 0 to 99, such that: “0 would indicate that you are at the very bottom … or more racist than almost everyone else, 50 would indicate that you were ‘exactly average’, and 99 would indicate that you were at the very top, or less racist than almost everyone else.”

We found that everyone gave themselves scores that were higher than 50, regardless of the context in which they were comparing themselves. That means that even when they were just considering how they ranked compared with the other people in the room with them on that day, every single person thought that they were less racist than the average. You don’t have to be much of a mathematician to understand that this is not how averages work.

How can we possibly square these two findings – a world in which there is widespread, significant, detectable racism, but simultaneously a world in which hardly anyone, anywhere admits, even to themselves, that they think, feel, or do racist things?

The term “unconscious bias” is now very widely used. For example, in the 2022 documentary series Harry & Meghan, Prince Harry, Duke of Sussex (whom I consider both well intentioned and reasonably well informed about racism for a very rich, very privileged, very White man), used it to explain both his earlier racist behaviour and some of the attitudes of other members of his family. There are many, many books about unconscious bias, including some I really like, such as The Authority Gap by Mary Ann Sieghart. However, unconscious bias was not the term used by Anthony Greenwald, Brian Nosek and Mahzarin Banaji, the team of scientists who, in 1998, invented and popularised these now widely used measures of hidden prejudice. In fact, they only mention the word “unconscious” once in their original scientific paper. The term they use most often is “implicit”. This seemingly subtle difference in terminology is important because implicit bias and unconscious bias mean quite different things.

Research on implicit bias covers a multitude of different types of bias that individuals are “unwilling or unable” to report explicitly and accurately. It is a set of tools – among them the implicit association test (IAT), which measures attitudes and beliefs that people may be unwilling or unable to report – that allows us to better predict who will pick the White CVs over the Black CVs, who will rate the White student’s work as better than the Black student’s work, or who will schedule the White patient’s appointment sooner than the Black patient’s appointment, even if the person in question is unwilling or unable to admit to doing those things. That’s the crucial part: the tests don’t rely on the person’s awareness of their own bias or their preparedness to honestly tell you.

In contrast, the unconscious bias narrative sweeps away two of the important reasons why someone might be unwilling or unable to report their levels of bias. It ignores both simple deception and complex psychological trickery, leaving us with a narrative in which most or all people are entirely, and innocently, unaware of their own biases. This makes it restrictive and myopic. And this myopia is dangerous.

As an example, in 2019 scientist Natalie Daumeyer and colleagues conducted four studies on how people interpret and respond to bias. In one of these studies, they recruited 299 participants and got them to read stories about doctors who were treating their patients differently depending on their group membership – in other words, doctors who were behaving with detectable bias towards some of their patients. All of the participants read the same scenarios, with only one crucial difference. Half of the participants also read that the “doctors were somewhat aware they were treating patients differently”, while the other half of the participants read that “the doctors had no conscious knowledge that they were treating patients any differently”.

And what did the researchers find? That framing bias as “unconscious” made the participants care less about the bias. Specifically, even though the doctors’ behaviour was the same and the effect on their patients was the same, Daumeyer’s participants were less concerned about the bias, thought that the doctors should be less accountable for it, and were less convinced that anyone should be punished for it, if they thought of the bias as unconscious rather than conscious.

As a social psychologist, these findings put me in a tough position. A huge number of people still don’t even believe that contemporary racism exists. Despite the mountains of empirical evidence confirming that racism is a part of almost everything, almost everywhere, almost all the time, people are still stuck in a conversation about whether or not it is even happening. In that light, one would think that the proliferation of the unconscious bias narrative is the answer to a social psychologist’s prayers. Finally, people are acknowledging that bias is real and pervasive. Finally, everyone is talking about contemporary bias and even referring to some scientific papers when they do it. From this perspective, one might assume that the unconscious bias narrative is a blessing. But it is not.

I’m sure it feels as if we’re doing something good with all this discussion of unconscious bias. It is, after all, important to finally acknowledge our biases. However, the research shows that if all we’re acknowledging is unconscious bias, then what we’re really doing is protecting our own perceptions of innocence, reducing our concerns about the bias we claim to be addressing and ensuring that nobody is ever held accountable for it. This is not what doing something good looks like. This is doing something bad.

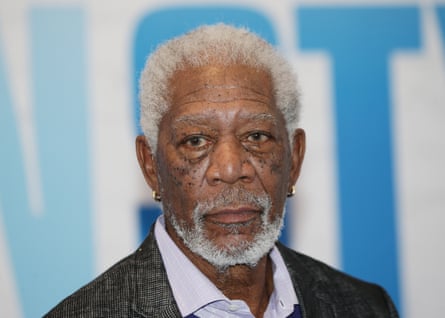

In 2005, in an interview on the American television show 60 Minutes, Mike Wallace (White and Jewish) asked Morgan Freeman (Black): “How are we going to get rid of racism?”, to which Freeman responded: “Stop talking about it. I’m going to stop calling you a White man and I’m going to ask you to stop calling me a Black man.” It appears that Freeman endorses what social psychologists call “colour blindness”. As I put it in an article that I published in 2021, colour blindness reflects “the belief that race should not and does not matter”. It is an approach to dealing with race and racism that explicitly discourages (as Freeman did) any reference to racial categories or any activity that acknowledges racial categories.

And, of course, Freeman is not alone. Former Black presidential candidate Ben Carson also supports colour blindness and claims the concept is based on the same desires as those of the Rev Dr Martin Luther King Jr’s dream of a nation where an individual is judged based on the “content of their character”, not the colour of their skin.

In the UK, in a 2023 interview with Alex Bilmes for Esquire, Idris Elba explained why he stopped describing himself as “a Black actor” and started describing himself as simply “an actor”. To be fair to Elba, in the same interview, he did explicitly acknowledge that racism was real, that it should be a topic of discussion, and that he was definitely a member of the Black community. However, he went on to say that racism is only as powerful as you allow it to be, that people are too “obsessed” with race and that this “obsession” can hinder growth. He doesn’t want to be thought of as the first Black this or the first Black that, just as the first Idris Elba.

A lot of people (or at least, most White people in predominantly White western countries) do think that colour blindness – the unwillingness to notice or acknowledge race – is good. And that is a real shame, because colour blindness is a terrible idea. More colour blindness doesn’t result in less racism. It wouldn’t even be fair to say that colour blindness is ineffective at reducing racism. It’s much worse than that. A wealth of research shows that adopting a colour-blind approach will make you significantly more racist in a number of important ways.

In 2021, I recruited 287 British participants and tested them on their levels of a number of variables: colour blindness (I asked how much they agreed with statements such as: “It is important that people begin to think of themselves as British and not Black British or Asian British”); explicit racism (for instance, “Black [people] should not push themselves where they are not wanted”); implicit racism (I had them complete an IAT); and narrow definitional boundaries of racism (such as: “The core of anti-Black racism is that it is malicious: if a person is not being malicious, then it can’t be racism”).

This was just a correlational study, and every first-year university student of psychology knows that correlation doesn’t equal causation. Still, if colour blindness were a good thing, we could reasonably expect that as levels of colour blindness go up, levels of implicit racism, explicit racism and narrow definitional boundaries should go down. But that was not at all what we found. We didn’t even find that levels of colour blindness were unrelated to levels of these bad things. Instead, we found sizable, highly statistically significant, positive correlations between colour blindness and implicit racism, explicit racism and narrow definitional boundaries of discrimination. Put simply, participants who were more colour-blind were also more racist, both implicitly and explicitly, and less willing to recognise racism.

Colour blindness is worse than ineffective against racism. It’s a disaster. We’re seeing some of that disaster unfold in real time. In 2023, the US supreme court called an end to affirmative action policies in university selection. In the BBC’s reporting of the outcome, it was said that “the six conservative justices in the majority heralded the decision as a step toward a more colour-blind society”. How right they were. Except that’s not something to herald, because a “more colour-blind society” is, scientifically, a more racist one.

It is not a strategy for reducing racism, merely for ignoring it. But we’re not children any more. And it is silly to believe, of a problem as large and as powerful as racism, that if we ignore it, it will just go away.

-

This is an edited extract from The Science of Racism: Everything You Need to Know But Probably Don’t – Yet by Keon West, published by Picador on 23 January (£20). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply

This post was originally published on here