This post was originally published on here

Understanding how bacteria regulate their genes is key factor of modern biology. It shapes how we study microbial behaviour, design antibiotics and use bacteria for producing compounds of industrial or medical value. For decades a single framework the σ (sigma) cycle has guided our understanding of how bacteria initiate and sustain gene expression. According to this classic model, sigma factors bind to RNA polymerase to start transcription and detach once RNA synthesis begins. This view was derived mainly from research on Escherichia coli, has been repeated in classrooms, textbooks and laboratories for nearly fifty years.

A new study from the Bose Institute, Kolkata and Rutgers University now challenges this foundational idea. Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the research demonstrates that this sigma-release cycle is not universal. In some bacteria, key sigma factors remain attached to RNA polymerase throughout the transcription process, pointing for a re-examination of long-held assumptions about bacterial gene regulation.

Model Built on a Narrow Foundation

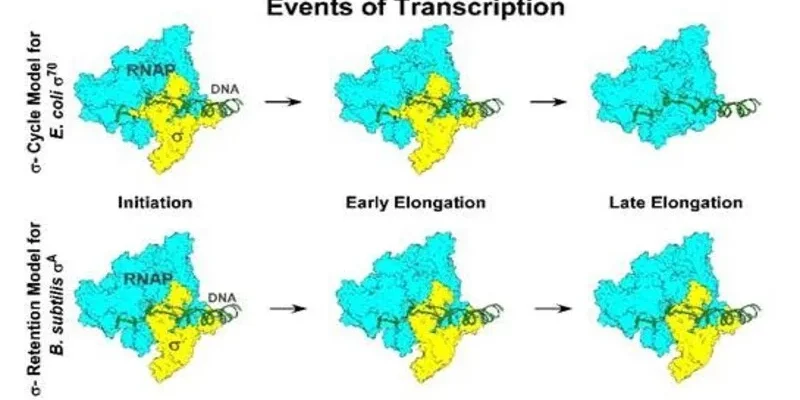

Textbook explanations of transcription initiation in bacteria rely heavily on findings from E. coli and its primary sigma factor σ⁷⁰. In this model, sigma helps RNA polymerase recognise promoter DNA. Once transcription begins, sigma dissociates by allowing elongation to proceed efficiently. This cycle of binding and release has been widely assumed to apply across bacterial species.

Their gene regulatory mechanisms often reflect the unique ecological pressures they navigate from soil environments to human hosts. A model derived from one organism cannot automatically represent all others, especially across lineages separated by large evolutionary distances. The new study underscores this gap by revealing a fundamentally different behaviour of sigma factors in the widely studied bacterium Bacillus subtilis.

The research team investigated σA, the principal sigma factor of Bacillus subtilis and a modified variant of E. coli σ⁷⁰ lacking a structural segment known as region 1.1. Using biochemical approaches, chromatin immunoprecipitation and advanced fluorescence-based imaging, the scientists observed sigma activity in real time. Their findings were clear unlike σ⁷⁰ in E. coli, both B. subtilis σA and the engineered σ⁷⁰ variant remained tightly associated with RNA polymerase during the entire transcription process

This behaviour contradicts the classical sigma-cycle model. The full-length E. coli σ⁷⁰ does eventually dissociate, but even in that system, its release is stochastic rather than strictly timed. These observations suggest that sigma retention during elongation may be more common than previously thought. The long-held assumption that sigma detaches after initiation is now shown to be incomplete. Dr. Jayanta Mukhopadhyay of the Bose Institute emphasises the significance of the discovery such as the persistence of σA throughout transcription “fundamentally changes how we think about bacterial transcription and gene regulation”

His colleague Dr. Aniruddha Tewari adds that the findings “provide compelling evidence that the long-accepted σ cycle does not apply to all bacteria,” opening up new pathways for exploring the evolution and diversity of bacterial regulation.

Implications for Microbiology and Antibiotic Development

Understanding how sigma factors behave has practical consequences far beyond academic interest. Sigma factors are the gatekeepers of transcription and their interaction with RNA polymerase defines the when and how of gene switching on particularly under stress conditions such as nutrient limitation or host immune pressure.

If different bacteria use different regulatory strategies, then antimicrobial therapies targeted to one mechanism will not be universally effective. Since many antibiotics exert their action through disruption of transcription, a more nuanced understanding of the dynamics of sigma-polymerase interaction could inform the design of inhibitors with narrower spectra of activity. Knowledge of sigma remaining attached in certain species could enable novel strategies either for blocking transcriptional initiation or prolonging polymerase stalling during elongation.

Bacteria whose sigma-polymerase interactions are stable may control stress responses in a different way from those whose interactions are transient. This could influence how pathogens adapt to hostile environments within a host or how environmental bacteria resist toxins. Identifying groups of bacteria with similar transcriptional architectures could also help classify organisms with previously unknown regulatory systems.

New Opportunities for Synthetic Biology

These findings also have significant implications for industrial and environmental biotechnology where bacteria are commonly engineered to make enzymes, therapeutic molecules and bio-based materials. Such engineering depends significantly on predictable gene expression systems.

Depending on whether sigma behaviour varies between species, synthetic biologists may have to adjust the design of promoters and other transcription control elements more carefully. Stable sigma-polymerase complexes may provide certain advantages in the construction of high-yield production strains. It may be possible to enhance transcriptional stability in engineered microbes by modifying sigma function or by mimicking the retention seen in B. subtilis.

Study also suggests that better control over gene regulation could lead to improved production of various biofuels, biodegradable plastics or medically valuable compounds. Thus, the finding directly contributes to the increasingly important interface between molecular biology and sustainable technology.

Call to Revise Textbooks and Further Research

Scientific knowledge is subject to constant refinement. The sigma cycle model is widely accepted but needs updation of the current facts. While it remains very useful in descriptive purposes regarding transcription in E. coli, generalizing to all bacteria no longer holds. The diversity uncovered in this study urges microbiologists to reexamine assumptions about other regulatory factors once believed to uniformly behave across species.

The study emphasizes the contribution of modern bioimaging tools coupled with biochemical techniques. Such integrated approaches allow researchers to monitor events at a molecular level in real time, revealing subtlety that could not be detected through earlier techniques. The new findings by the Bose Institute and Rutgers University represent a leap forward in microbiology. In showing key sigma factors can stay bound through full transcription, this study dismantles a long-held textbook paradigm and reflects the growing complexity of bacterial gene regulation. This nuance is needed-not only to describe microbial biology correctly but also to develop antibiotics intelligently, conduct bioengineering sensitively and probe evolutionary questions effectively.

As scientists dig deeper into the variety of the microbial world, such findings remind us that even some of the most settled models will continue to shift. It’s the nature of scientific progress where refinement is advancement and returning to fundamental ideas can result in some of the most significant advances.