This post was originally published on here

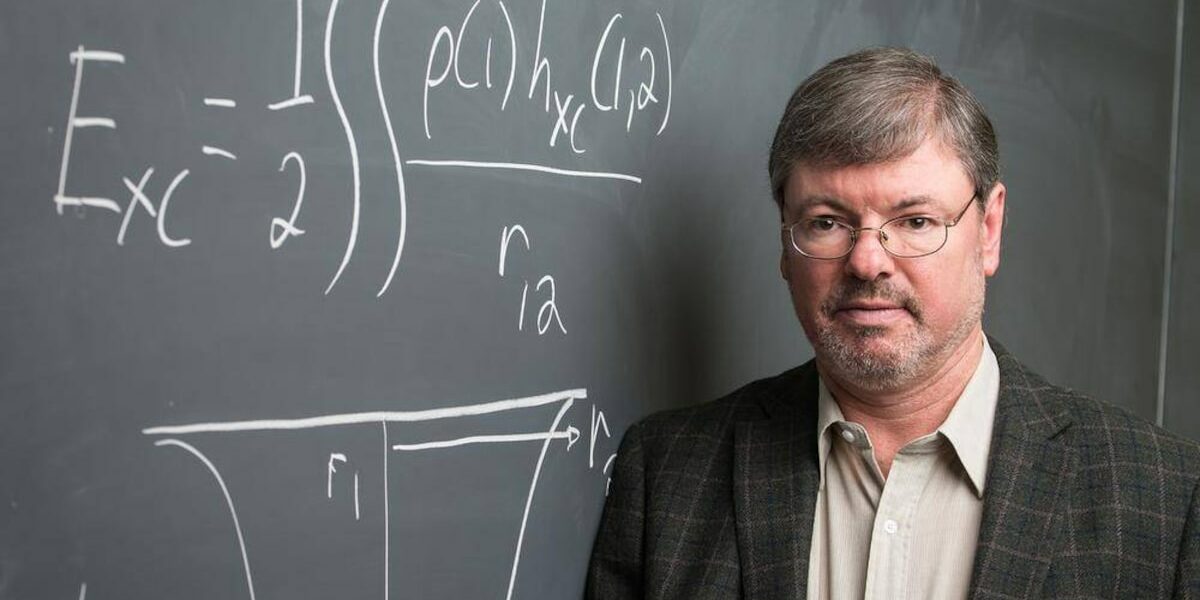

Dr. Axel Becke was known for his work on density functional theory, a mathematical tool that reveals how molecules derive their form and function from the behaviour of their electrons.Supplied

In 2015, when Axel Becke was awarded the Herzberg gold medal, Canada’s top prize for science and engineering, he was asked in an interview to explain who in the field of chemistry made use of the methods he had discovered.

Without pausing, Dr. Becke answered, “Everybody.”

It was no boast. Dr. Becke was known for his work on density functional theory, a mathematical tool that reveals how molecules derive their form and function from the behaviour of their smallest constituents, electrons. Over the course of his career, Dr. Becke helped to turn the theory into an effective user’s manual for matter.

A professor emeritus at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Dr. Becke died suddenly of natural causes on Oct. 23. He was 72.

Although he shunned the spotlight and preferred to work on his own or with just a few collaborators, Dr. Becke was a leading expert on what is called the “electronic” structure of molecules. His insights are embedded into computer software that is now used by scientists the world over to accurately predict the behaviour of matter under a myriad of circumstances that range from pharmaceuticals to construction materials.

“He was a giant in the theoretical chemistry community, not just in Canada but across the globe,” said Jason Pearson, a professor of chemistry at the University of Prince Edward Island who worked with Dr. Becke as a graduate student.

Dr. Pearson added that Dr. Becke earned his reputation by doing what academics are not well incentivized to do in Canada: thinking hard about fundamental concepts that can transform an entire field.

In 2014, Dr. Becke reflected on the widespread utility of density functional theory for a story in the journal Nature. The story considered the impact of the top 100 most cited scientific papers up to that point in history. One of Dr. Becke’s papers, published in 1993 in the Journal of Physical Chemistry, ranked eighth on Nature’s list.

The achievement was all the more impressive because Dr. Becke was the sole author. (According to the website Google Scholar, the paper has now been cited more than 120,000 times.)

“The applications are endless,” he told Nature then, noting that density functional theory “can be used to describe all of chemistry, biochemistry, biology, nanosystems and materials.”

So significant was Dr. Becke’s contribution to density functional theory that many colleagues said he deserved to be named alongside the theory’s originators, Walter Kohn and John Pople, when they were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1998.

Yet it was also well known that Dr. Becke, though unfailingly friendly and personable, did not seek out attention or professional honours and tried hard to minimize their intrusion on his work.

“He was a fantastic researcher in his field of endeavor and a very warm person, but very reticent about being showcased,” said Howard Alper, a chemist and professor at the University of Ottawa who formerly led a Governor-General’s initiative to raise the profile of Canada research talent worldwide.

Obituary: Brilliant diplomat David Malone helped Canada win a seat on the UN Security Council

Those who were closest to Dr. Becke recalled his discomfort with the idea of public recognition.

“He thought the idea that he may at some point be a Nobel Prize winner was the worst possible outcome for his life,” his brother, Peter Becke, told The Globe and Mail in an interview. “He couldn’t figure out how he could do what he wanted to do and live with that kind of fame and expectation.”

Dr. Becke also did not derive profits from his work, though it has become a mainstay of computer methods for chemical analysis. When it came to his science, he desired nothing more than to immerse himself in the work and try to make progress on questions and research puzzles that density functional theory put before him.

“He always wanted thinking time. That was the most valuable thing for Axel,” said Erin Johnson, a former graduate student and later a fellow faculty member at Dalhousie. “He wanted time to be by himself, at home or at a coffee shop and think about his ideas.”

Axel Dieter Becke was born on June 10, 1953, in Nellingen auf den Fildern, a small German town 50 kilometres southeast of Stuttgart.

When he was three years old, he moved to Canada with his parents, Helmut and Hannelore, and a younger brother, Tom. After a short time in Toronto, the family settled first in London, Ont.

Helmut, who had been an apprentice glassblower in Germany, found work making neon signs — a ubiquitous feature of the 1950s landscape and a source of extra income when he and Hannelore took on side projects at home.

The family next moved to Burlington, Ont., when Helmut took a job making scientific glassware for the chemistry department at nearby McMaster University in Hamilton. For young Axel, his father’s new role offered a first glimpse at an intriguing world filled with test tubes and other laboratory paraphernalia, which helped to spark his interest in science.

During those years, Meccano sets and Lego blocks made regular appearances under the Christmas tree. At a memorial service for Helmut, who died this year at age 100, Dr. Becke recalled his father bringing home a chemistry textbook he had found at work.

“I devoured it cover to cover,” Dr. Becke said.

The influence on Axel deepened after 1970 when his father moved to Bell-Northern Research, an Ottawa based R&D company — later to become part of Nortel — where he worked with specialized glass for semiconductor manufacturing.

By then the family had grown to include four boys. At various times over the years, Axel, Tom, Peter and the youngest brother, Alan, all had summer jobs and other positions at the company.

“We all got interested in science in one way, shape or form and all worked in the technology industry,” said Peter Becke, now a venture capitalist and a senior adviser with a global law firm. “There’s no doubt that had to do with an immigrant coming over, seeing opportunity, being interested in science-based businesses or labs, and then the rest of the family kind of followed suit.”

As a teenager Axel also pursued other interests, including athletics, with impressive results. In 1970, he set a Canadian high school long jump record with a jump of 22 feet 8 inches. He also mastered the accordion, and in 1967 won the Canadian accordion championship for his age category.

But once he was in university, science took hold as his chief passion. In 1975 he earned his BSc in Engineering Physics at Queen’s University, winning a gold medal for top marks. From there he went to McMaster University, where he completed his MSc in 1977 and PhD in 1981. Following a postdoctoral stint at Dalhousie, he then joined the faculty at Queen’s in 1984.

By then he had already become fascinated with the concept of the chemical bond — a bridge created by shared electrons that ties atoms into molecules and molecules into the solids and surfaces of everyday life. He understood that the quantum nature of subatomic particles presented a challenge when it came to calculating the energy and strength of chemical bonds. Density functional theory suggested how this might be accomplished. It was Dr. Becke who made the approach practical.

Innovative researcher Mitchell Halperin advanced the understanding of kidney physiology

A career turning point was a lunchtime conversation Dr. Becke had with one of the theory’s originators, John Pople, during a 1991 scientific meeting in France. By the end of the meal Dr. Pople was convinced of Dr. Becke’s approach and later incorporated it into a widely used chemistry software package developed by his group at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

According to Dr. Johnson, Dr. Becke had transformed “something that was perhaps theoretically elegant but not terribly useful for chemistry applications into something that was sufficiently accurate that computational chemists around the world wanted to start using it.”

Awards and accolades followed, including the Herzberg medal, the Killam Prize from the Canada Council and an excellence in teaching award from Queen’s University, among others. But Dr. Becke was known best for his research. In 2000 he was elected to the Royal Society of Canada and then became a Fellow of the Royal Society of London in 2006. It was during that year that he moved to Dalhousie University and he remained an active professor there until retiring in 2015. Even then he continued to work with graduate students and to publish new research work on his own as recently as last year.

One fellow faculty member, Mary Anne White, recalled the reluctance Dr. Becke expressed when he had to attend a dinner with colleagues to celebrate his induction into the Nova Scotia Science Hall of Fame in 2015.

In the end, what made the evening an enjoyable one was a set of Tinkertoys at each table that guests were required to use to build a small catapult.

“He practically had to be dragged there to go to this dinner,” Dr. White said. “But when we were playing these games at the table, he was totally into it. He was so relaxed.”

Dr. Becke was married but long estranged from his wife. They had no children.

He leaves his mother, Hannelore, 91, and three brothers.

You can find more obituaries from The Globe and Mail here.

To submit a memory about someone we have recently profiled on the Obituaries page, e-mail us at [email protected].