This post was originally published on here

Scientists at the University of Leicester have uncovered two remarkable new fossils, tiny prehistoric pterosaurs with broken wings.

University of Leicester paleontologists have uncovered the long-hidden cause of death for two baby pterosaurs, solving a mystery that has waited 150 million years for an explanation.

Published in Current Biology, the research reveals that the young flying reptiles were killed by intense storms. Those same storms created the perfect conditions to preserve their remains, along with hundreds of other fossils found in the region.

Why Solnhofen preserves so many small pterosaurs

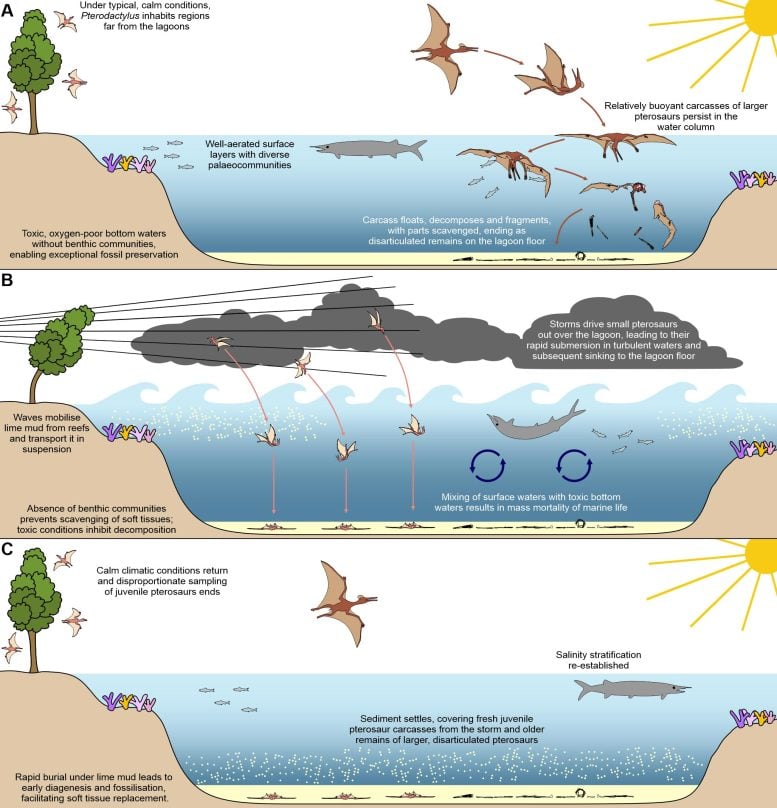

The Mesozoic era, often called the age of reptiles, is commonly pictured as a world dominated by enormous creatures. Museum exhibits and popular imagery feature giant dinosaurs, massive marine predators, and pterosaurs with enormous wingspans. In reality, ancient ecosystems resembled modern ones in at least one important way: most animals were small. The problem is that fossilization tends to favor large, sturdy organisms, and the bones of tiny, delicate animals rarely survive long enough to enter the geological record.

Even so, certain environments occasionally preserve these fragile species in remarkable detail. One of the best known examples is the 150-million-year-old Solnhofen Limestones in southern Germany. These lagoonal deposits are famous for their exceptional fossils, including numerous pterosaurs.

Yet a puzzling pattern emerges. Solnhofen contains hundreds of pterosaur fossils, but nearly all of them are very small and very young. Fully grown individuals are exceedingly rare, and when they do appear, they are usually represented only by scattered skull pieces or limb fragments. This is the opposite of what scientists would expect, since larger and more robust animals usually fossilize more easily than tiny juveniles.

Lead author Rab Smyth, from the University of Leicester’s Centre for Palaeobiology and Biosphere Evolution and funded by the Natural Environment Research Council through the CENTA Doctoral Training Partnership, highlighted the challenge: “Pterosaurs had incredibly lightweight skeletons. Hollow, thin-walled bones are ideal for flight but terrible for fossilization. The odds of preserving one are already slim and finding a fossil that tells you how the animal died is even rarer.”

Rab said: “Pterosaurs had incredibly lightweight skeletons. Hollow, thin-walled bones are ideal for flight but terrible for fossilization. The odds of preserving one are already slim and finding a fossil that tells you how the animal died is even rarer.”

Fossil injuries reveal deadly ancient storms

The discovery of two infant pterosaurs with damaged wings offers a key piece of evidence that helps resolve this long-standing puzzle. Although small enough to miss at first glance, the fossils provide striking support for the idea that ancient tropical storms played a major role in shaping which animals were preserved.

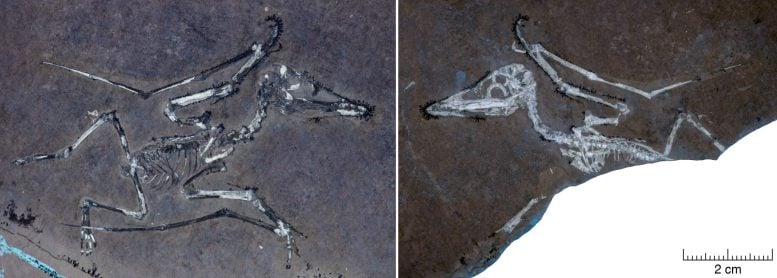

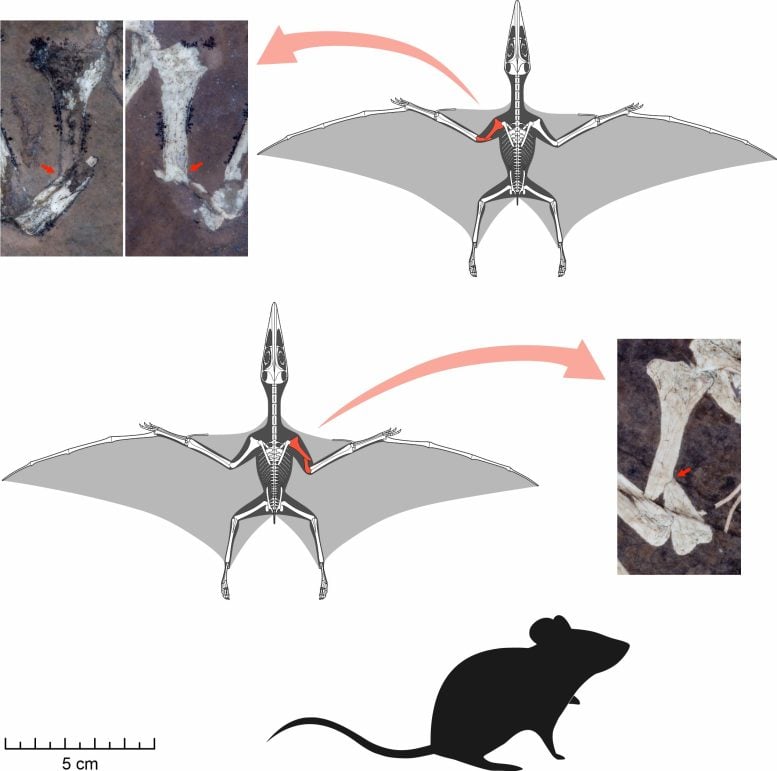

The researchers informally named the pair Lucky and Lucky II. Both belong to Pterodactylus, the first pterosaur species ever given a scientific name. Each hatchling had a wingspan of less than 20 cm (8 inches), placing them among the tiniest pterosaurs known from the fossil record. Their skeletons are complete, still connected bone by bone, and remain almost exactly as they were at the moment of death.

There is, however, a crucial detail. Each fossil shows the same distinctive break: a clean, angled fracture in the humerus. Lucky’s injury occurred in the left wing, and Lucky II’s in the right. The pattern indicates that the wings were twisted with significant force, a type of trauma more consistent with violent gusts of wind than with impact against a solid surface.

Catastrophically injured, the pterosaurs plunged into the surface of the lagoon, drowning in the storm-driven waves and quickly sinking to the seabed, where they were rapidly buried by very fine limy muds stirred up by the death storms. This rapid burial allowed for the remarkable preservation seen in their fossils.

Storms shaped the entire Solnhofen ecosystem

Like Lucky I and II, which were only a few days or weeks old when they died, there are many other small, very young pterosaurs in the Solnhofen Limestones, preserved in the same way as the Luckies, but without obvious evidence of skeletal trauma. Unable to resist the strength of storms, these young pterosaurs were also flung into the lagoon. This discovery explains why smaller fossils are so well preserved – they were a direct result of storms, a common cause of death for pterosaurs that lived in the region.

Larger, stronger individuals, it seems, were able to weather the storms and rarely followed the Luckies’ stormy road to death. They did eventually die though but likely floated for days or weeks on the now calm surfaces of the Solnhofen lagoon, occasionally dropping parts of their carcasses into the abyss as they slowly decomposed.

New insight into pterosaur diversity

“For centuries, scientists believed that the Solnhofen lagoon ecosystems were dominated by small pterosaurs,” said Smyth. “But we now know this view is deeply biased. Many of these pterosaurs weren’t native to the lagoon at all. Most are inexperienced juveniles that were likely living on nearby islands that were unfortunately caught up in powerful storms.”

Co-author Dr David Unwin from the University of Leicester added: “When Rab spotted Lucky, we were very excited but realized that it was a one-off. Was it representative in any way? A year later, when Rab noticed Lucky II we knew that it was no longer a freak find but evidence of how these animals were dying. Later still, when we had a chance to light-up Lucky II with our UV torches, it literally leapt out of the rock at us – and our hearts stopped. Neither of us will ever forget that moment.”

Reference: “Fatal accidents in neonatal pterosaurs and selective sampling in the Solnhofen fossil assemblage” by Robert S.H. Smyth, Rachel Belben, Richard Thomas and David M. Unwin, 6 October 2025, Current Biology.

DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.08.006

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.