This post was originally published on here

Scientists are urging for greater cross-sector collaboration with the key players, which uses krill for food and supplements, to secure ocean stocks for the future. They encourage viewing the industry less as an opponent and more as a partner.

Nutrition Insight speaks with Alfred Wegener Institute’s (AWI) biologists to learn why it is essential for industry and scientists to work together for optimal krill management.

They warn that if stocks fall due to overfishing, several animals, such as seals, fish, penguins, and baleen whales, that only rely on krill would be directly harmed. Krill are one of the most abundant wild animals, ranking second in the Antarctic food web.

Humans are now a part of the food web, using krill for food supplements like omega-3 fatty acid oil and aquaculture feed pellets.

Although every fishing vessel must have a scientific observer on board to collect data since 2020, this data is not included in the current krill monitoring, Dr. Bettina Meyer, head of the working group Ecophysiology of pelagic key species at the AWI and professor at the University of Oldenburg, Germany, tells us.

She posits that fishing vessels should be viewed as research platforms for collecting critical data.

The Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) regulates krill fishing and promotes sustainable practices via scientific monitoring. Meyer cautions that last year, CCAMLR members were unable to agree on the regulation’s continuation.

By July of this year, the amount of krill fished in Antarctic Peninsula region (sub-area 48.1) had more than doubled to nearly 0.4 million tons due to the lack of regional restrictions, Meyer warns. Also, the maximum allowed catch in the entire fishing area 48 had been reached for the first time.

She adds that it is unclear what the impacts of this would pertain to.

This year’s CCAMLR October meeting led to no formal agreement, although industry player Aker BioMarine believes the possibility of consensus is closer. The meeting confirmed: “When industry, NGO’s, scientists, and nations work together with genuine intent, progress is possible.”

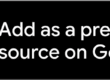

Krill plays a central role in the Antarctic food web, supporting species from penguins to baleen whales — making sustainable management crucial (Image credit: Carsten Pape).Meyer believes that monitoring fishing vessels is possible, but it is not a viable option for CCAMLR states due to economic interests. Instead, she bets on close cooperation with the fishing industry that could multiply scientific data and paint a clearer picture of krill populations.

Krill plays a central role in the Antarctic food web, supporting species from penguins to baleen whales — making sustainable management crucial (Image credit: Carsten Pape).Meyer believes that monitoring fishing vessels is possible, but it is not a viable option for CCAMLR states due to economic interests. Instead, she bets on close cooperation with the fishing industry that could multiply scientific data and paint a clearer picture of krill populations.

Is “sustainability” mostly marketing?

Meyer notes that the industry shows a “general willingness” to be involved in krill fisheries management.

“For example, it has implemented voluntary measures like Voluntary Restricted Zones (VRZs) near penguin colonies during their breeding season and supported scientific research by conducting krill biomass surveys to support krill fishery management under CCAMLR to balance industry growth with ecosystem protection.”

Dominik Bahlburg at AWI tells us that most of these efforts are carried out via the Association of Responsible Krill harvesting companies, which is an industry group promoting sustainable Antarctic krill fishing.

“While this willingness is generally welcomed, it should also be noted that, for instance, VRZs do not really affect fishing operations, as the fishery typically operates in other regions during that time of the year.”

“The effectiveness of VRZs is therefore questionable. Whether the fishery is really willing to make the substantial contributions required for revised krill fisheries management, however, remains to be seen,” he notes.

Specific and collaborative roles

Krill plays an essential role in creating the foundation of Antarctic life while also serving as a source of essential nutrients. According to Meyer, this balance must be maintained collaboratively while ensuring different responsibilities.

“Scientists supply the factual information, such as population estimates, ecosystem models, trophic impact assessments, and monitoring concepts. They communicate uncertainties and recommend precautionary limits and monitoring indicators.”

“The fisheries management authority, like CCAMLR, on the other hand, sets regulations, quotas, closed seasons (spatial/temporal), enforcement measures, and mandates independent monitoring.”

“The industry, which complies with these rules, funds regular monitoring and employs sustainable fishing practices to safeguard the ecosystem by reducing bycatch and ensuring traceability and transparency within the supply chain,” she explains.

Scientists say fishing vessels could become essential research platforms, helping monitor krill populations amid rising catch volumes.Bahlburg points to the AWI’s recent publication in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, containing co-management structures, as a possible viable approach for the future, with industry funding krill monitoring while independent bodies scientifically implement designated programs.

Scientific integrity and economic interests

According to Bahlburg and Meyer, scientific data from the krill industry can be kept unbiased and separate from economic interest by preparing transparent contracts between science institutions and industry. Importantly, it should ensure the independence of science.

“It is also important to establish independent funding mechanisms, such as industry contributions going into an independent science fund, administered by a neutral body, that awards competitive grants to researchers, rather than industry commissioning specific studies,” says Bahlburg.

Meyer adds another factor: “Having independent observers on fishing vessels and implementing observer programs alongside electronic monitoring (cameras/GPS) operated by third parties helps to reduce bias in catch and effort data.”

Bahlburg highlights other measures: “Binding data sharing agreements with monitoring data being submitted to the CCAMLR secretariat and independently assessed, e.g., through the CCAMLR Working Groups, to produce unbiased scientific advice for policy makers.”

AWI calls for transparent industry-science collaboration to better manage krill population to protect predators and balance human resource use.These criteria enable practical partnerships while safeguarding science from commercial incentives, they note.

AWI calls for transparent industry-science collaboration to better manage krill population to protect predators and balance human resource use.These criteria enable practical partnerships while safeguarding science from commercial incentives, they note.

Sustainable supply chain

Bahlburg and Meyer explain that a sustainable omega-3 supply chain concerning the krill fishery requires a resilient, low-impact supply chain that meets nutritional needs while protecting the marine ecosystem.

“This would involve demand reduction and diversification, strict standards for krill harvesting, and full transparency,” Bahlburg notes.

“This would include ecosystem-based fisheries management where catch limits are derived on the basis of the krill stock status, krill biology, and predator demands; spatial and temporal allocations of catch limits to protect predators; and adaptive management triggered by ecosystem indicators.”

Meyer adds that full traceability and transparency mean digital chain-of-custody, such as batch IDs and public landing records, while third-party audits ensure claims match reality.

“Meanwhile, low-impact fishing practices minimize bycatch and habitat disturbance, thereby limiting transshipment, and use observer or electronic monitoring. Lastly, for independent monitoring and public data, there should be mandatory scientific observers, biomass surveys, and open access to monitoring data,” she concludes.

Krill trawling

Nutrition Insight has investigated krill trawling extensively this year. In June, we spoke to Matts Johansen, CEO of Aker BioMarine, about balancing the demand for krill-based supplements with the need to protect fragile marine ecosystems. He also highlighted the rise of plant-based nutrition alternatives sourced from algae.

The British Antarctic Survey also warned of risks if fishing occurs during breeding seasons. It detailed how interim measures controlling fishing across different Antarctic regions lapsed last year, which risks overfishing in certain areas.

In October, the WTO reached an agreement on Fisheries Subsidies to prevent fish depletion and protect fishing communities’ livelihoods. By cutting subsidies, the landmark move curbs government support for illegal fishing and the exploitation of stocks to protect marine life.

Also, the UN High Seas Treaty will go into effect in January, allowing for the establishment of marine protected areas in international waters with the goal of protecting 30% of the ocean by 2030.