This post was originally published on here

The Death—and Rebirth—of Science Diplomacy

Once a vehicle for global cooperation, international science has become a high-stakes arena of geopolitical rivalry.

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer tours Palantir Technologies headquarters with company employees and British military personnel in Washington on Feb. 27. Carl Court/POOL/AFP

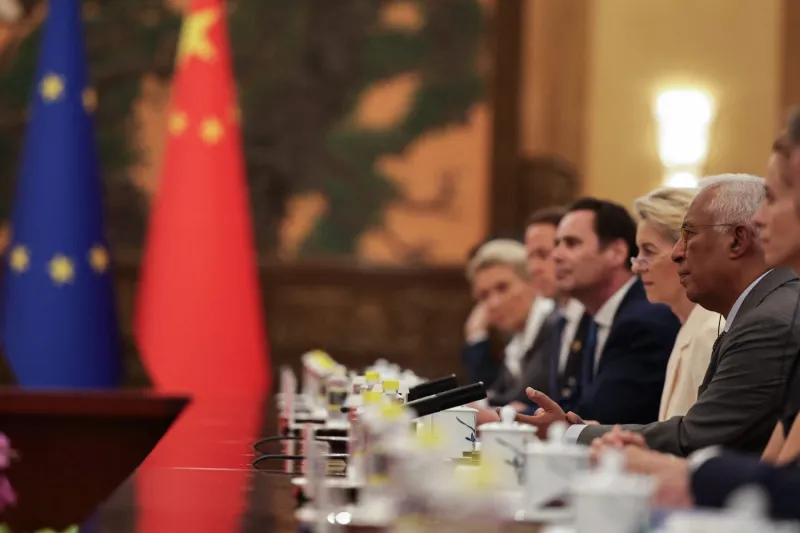

From Dec. 17-18, the Danish presidency of the Council of the European Union and the European Commission will convene the second European Science Diplomacy Conference, bringing 500 top-level policymakers, researchers, and field leaders to the table to confront an uncomfortable truth: The honeymoon of effortless international scientific cooperation is over.

Twenty years ago, international scientific collaboration seemed unstoppable. Student exchanges, joint research projects, and shared infrastructure were designed not just to advance knowledge and fuel innovation markets, but also to foster cosmopolitan values and strengthen diplomatic ties. Such undertakings depended on active government involvement through international science and technology agreements, targeted funding, and institutional matchmaking—and this convergence of science and statecraft became known as science diplomacy.

From Dec. 17-18, the Danish presidency of the Council of the European Union and the European Commission will convene the second European Science Diplomacy Conference, bringing 500 top-level policymakers, researchers, and field leaders to the table to confront an uncomfortable truth: The honeymoon of effortless international scientific cooperation is over.

Twenty years ago, international scientific collaboration seemed unstoppable. Student exchanges, joint research projects, and shared infrastructure were designed not just to advance knowledge and fuel innovation markets, but also to foster cosmopolitan values and strengthen diplomatic ties. Such undertakings depended on active government involvement through international science and technology agreements, targeted funding, and institutional matchmaking—and this convergence of science and statecraft became known as science diplomacy.

Science diplomacy was forged by the United States in the mid-1990s as a soft-power tool to create a friendlier American face abroad via science’s global prestige. Gaining momentum alongside the rise of globalization and multilateral cooperation, science diplomacy reached its height around the turn of the millennium, when scientific collaboration was widely understood as both a driver of innovation and a pillar of liberal internationalism.

As highly industrialized countries in Europe followed suit, international higher education and science collaborations, no matter how small, were eagerly branded as acts of diplomacy in lab coats and turned into symbols of strategic influence. The European Union made science diplomacy its own in 2009 by strengthening European Research Area policies under the umbrella of the Treaty of Lisbon, which enabled Brussels to align research and foreign policy to tackle major challenges, fund massive joint infrastructure projects, and compete with other power blocs in an increasingly multipolar world.

Gone are the days, however, when international scientific collaborations were celebrated as collective, neutral achievements. After a string of jolting events, including the Arab Spring; the brutal crackdown on pro-democracy movements in Turkey; revelations of large-scale Chinese science espionage; and, finally, Russia’s assault on Ukraine, observers were quick to declare the demise of science diplomacy. Their verdict, dripping with jaded irony, was succinct: So much for soft power.

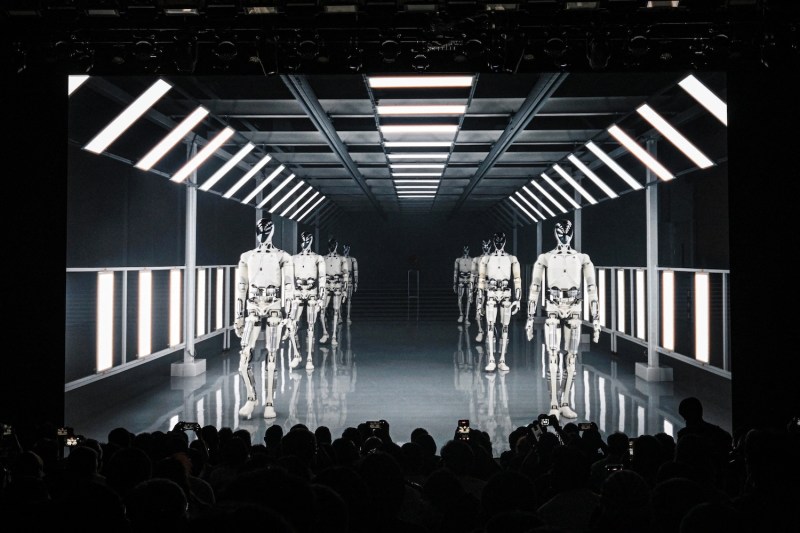

But science diplomacy is not dead; it is evolving. Once the domain of idealists and bridge-builders, science diplomacy is transforming amid the harsh glare of a fragmented, fast-moving world. As geopolitical rifts widen and technologies such as artificial intelligence and quantum computing redraw the global map, the age of open, apolitical research exchange is giving way to an era in which science functions as a strategic tool—and, at times, a weapon—in fierce contests for sovereignty, national power, economic might, and digital security.

In short, where science once symbolized cooperation, it now increasingly embodies competition. No longer idealized as a Woodstock festival of peace, love, and harmony, international science is now a high-stakes arena of geopolitical rivalry and strategic positioning.

Today, national interests are guiding international scientific partnerships, transforming science into a geopolitical battleground. The United States, China, and the EU are not just racing to innovate; they are also racing to control scientific breakthroughs in quantum computing, fusion energy, and biotechnology, among other sectors.

These research areas blur lines between civilian research and military application. Technologies that could once be neatly categorized as either having civilian or military use have become inherently intertwined, operating concurrently in both realms. Drones, for example, both optimize agricultural production and transform the landscape of war. Facial recognition can unlock one’s phone—or be used as a tool of surveillance and repression.

The realpolitik-infused science diplomacy of today is playing out not just in government labs but also in closed-door tech summits, corporate boardrooms, and the back channels of international organizations. Private tech giants and foundations have joined states as powerful research entities in and of themselves, and their influence often comes without public accountability, raising thorny governance questions about legitimacy and inclusion. Funding and power are increasingly decentralized, but who sets the rules—and who gets left behind—are questions splitting the field in scientific and policy circles alike.

In AI governance, for instance, the United States thus far has not meaningfully regulated or prohibited the use of new technologies, signaling to tech giants a permissive approach to AI regulation. The EU and the United Nations, on the other hand, are pursuing distinct paths: While the EU has developed its AI Act based on an agile and risk-based approach, the U.N. has worked to build global consensus through nonbinding resolutions that depend on individual state compliance.

Even the frameworks used to define science diplomacy are being rewritten. Global heavyweights such as the United Kingdom’s Royal Society and the American Association for the Advancement of Science are shifting from models of open cooperation to hard-nosed strategies that prioritize national interest over the global common good.

The EU’s 2025 report on science diplomacy adds a new twist: Scientists themselves must develop diplomatic chops, as scientific advice is increasingly sidelined in political power games. The EU aims to equip scientists with diplomatic competencies, such as tact, negotiation, and sensitivity to cultural and political contexts, even within ostensibly scientific settings such as peer reviews or funding selection procedures. These environments, while technical in nature, can be politicized, requiring scientists to navigate them with the same awareness and skill traditionally reserved for diplomacy.

The global south is also redrawing the map. The expanded BRICS bloc (originally comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, and now including Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and others) is not just joining the science diplomacy conversation; it’s also rewriting the script, using research collaboration as a lever in global power rebalancing.

The 2024 BRICS summit in Russia situated science and technology cooperation at the heart of the agenda, highlighting areas such as artificial intelligence, renewable energy, biotechnology, quantum technologies, and space exploration as priorities for collective investment. A key outcome of the summit was the renewal of the BRICS Science, Technology and Innovation Framework Program, which aims to coordinate joint research projects, share infrastructure investment, and drive talent mobility across BRICS countries.

Across the world, four trends are reshaping science diplomacy.

First, geopolitical polarization is turning science into a national security issue, replacing free exchange with sanctions and techno-nationalism. A 2024 report by the International Association of Universities found that that geopolitical tensions have significantly disrupted international research links in Europe and North America, warning that national security and commercial priorities, especially in AI and data science, are replacing global collaboration with restrictive national policies. The report also called upon universities to counter political and corporate pressures by defending academic freedom and open inquiry, reflecting the shifting role of higher education in the realm of science diplomacy.

Second, emerging technologies are outpacing rules. According to Stanford University’s 2025 AI Index Report, almost 90 percent of notable AI models came from nonstate industry actors in 2024, up from 60 percent in 2023. Although many companies acknowledge the risks of responsible AI, a gap in translating awareness into substantive action persists.

While governments and international coalitions have demonstrated growing urgency in the need to regulate disruptive technology, increase transparency, and establish core principles of responsibility, none have captured the widening gap between AI application and regulation. Science diplomacy now demands prediction, not just reaction. Ultimately, pacts between technology companies and governments must be established to create agile and meaningful governance structures that balance innovation and risks.

Third, tech itself is transforming diplomacy. Traditional protocol diplomacy—namely embassies, consulates, and all the ceremonial paraphernalia—still exist, but satellites and AI, for instance, are part of the new diplomatic toolkit. To keep up with today’s technological pace, diplomacy needs to recruit tech geeks and scientists who can observe the pulse of global developments and help develop policy. Some foreign ministries have begun to integrate data scientists and digital analysts into their teams, but such initiatives are scattered and far from being adopted across the board.

Fourth, the global “war for talent” in science and technology, once a post-Cold War buzzword, has become hard reality. Further driven by wars, humanitarian crises, and rising anti-science sentiment in parts of the world on one hand and by mere demographic change on the other hand, science diplomacy actors must focus on creating the best conditions to attract and retain scholars and students. Headhunting, a practice long established in industry and domestic science management, could become a legitimate strategy for liberal democracies seeking to reframe recruitment as part of a welcoming culture.

Science diplomacy need not abandon its cosmopolitan ideals, but it must confront hard truths. Governments, corporations, universities, and researchers alike must recognize that in many countries, liberal democratic values and partnerships have already been forsaken, and they cannot be restored simply through scientific cooperation alone.

In this regard, science diplomacy has become a reminder of a stark reality: Science today is inseparable from transnational politics.

Researchers no longer operate in a vacuum; their work carries cross-border consequences. Integrating geopolitical awareness into their work, developing diplomatic literacy, and anticipating political risks while still advancing open, evidence-based exchange are now requirements for meaningful cooperation. By strengthening scientists’ diplomatic training and integrating policy relevance into research design processes, science diplomacy can evolve past symbolic gestures to concrete impact.

Policymakers, too, must recognize that international science ties are not just academic niceties but also strategic assets for economic survival and, in a world of critical technologies, national security itself. Recruiting more scientists and technology experts—and planting chief science advisors in foreign ministries—will be key for national government administrations and international organizations as well as a necessary strategy for global observatories as they work to align innovation policies with ethical and geopolitical considerations.

Science and technology cooperation should be valued as core components of foreign policy, and institutionalized channels linking scientists, policymakers, and competent members of civil society must be developed to build public trust and ensure that evidence-based expertise consistently informs decision-making.

The stakes could not be higher. Science diplomacy can no longer rely on nostalgia for an age of open exchange. Without a robust and strategic science diplomacy infrastructure, global efforts on climate action, digital governance, and public health will falter. Science diplomacy cannot solve every crisis, but it can shape how we respond to them by embedding science in the architecture of global decision-making and ensuring that evidence, not ideology, guides collective action.

Jan Lüdert is the head of programs at the German Center for Research and Innovation New York City.

Martin Wählisch is the inaugural associate professor of transformative technologies, innovation, and global affairs at the University of Birmingham’s Centre for Artificial Intelligence in Government.

Tim Flink is a manager for future and emerging technologies at the German Association of Research-Based Pharmaceutical Companies. He is a senior lecturer at Humboldt University Berlin and a former scientific advisor in the German Bundestag.

Stories Readers Liked

Trump’s National Security Strategy

What the 2025 National Security Strategy Means for Asia

The MAGA revolution in U.S. foreign policy brings good news and bad.

Join the Conversation

Commenting is a benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Already a subscriber?

.

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

View Comments

Change your username |

Log out