This post was originally published on here

In the first fractions of a second after the Big Bang, the universe ballooned outward at a speed that still defies explanation, stretching space itself before stars or even atoms had a chance to form. Cosmologists call this moment inflation, and for decades it has remained frustratingly abstract, etched into equations but with no reference in physical observations.

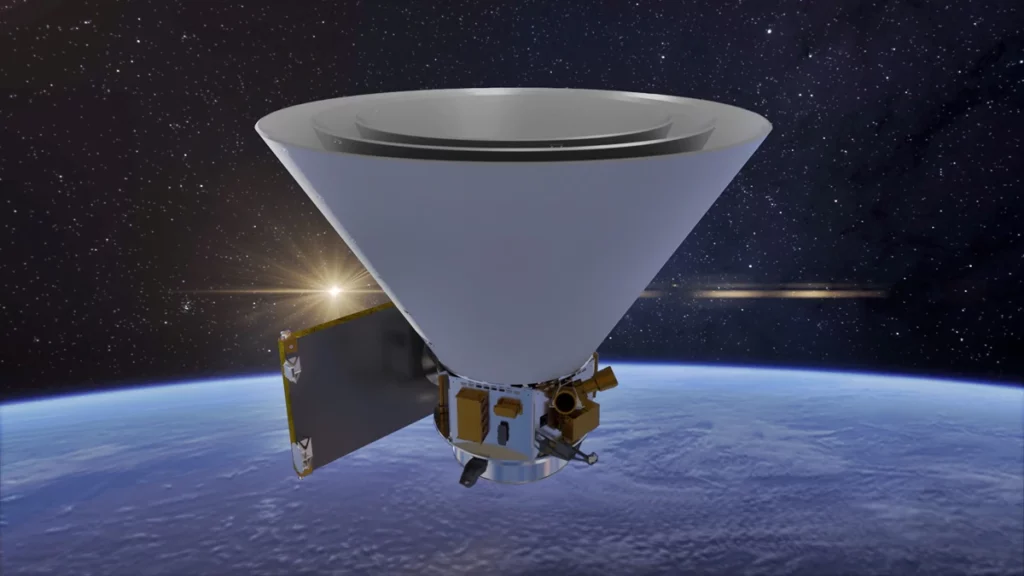

Now, a new space telescope has begun to trace inflation’s fingerprints across the modern universe.

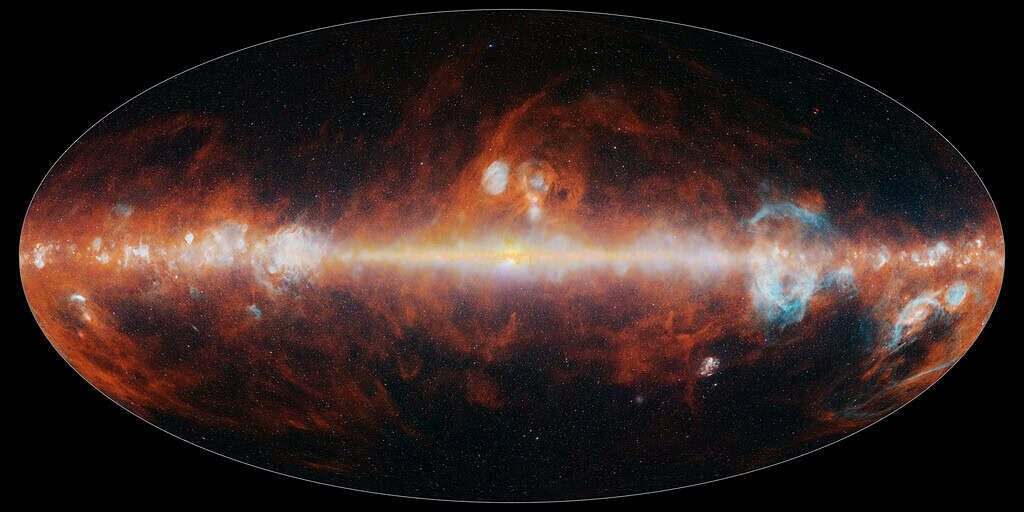

Just months after launch, NASA’s SPHEREx mission has completed its first full map of the entire sky, capturing the cosmos in 102 different infrared wavelengths. The result is not a single picture but a layered, multidimensional archive that scientists say could help explain how the universe developed into the structure of today — and how it eventually produced galaxies, planets, and maybe life.

“It’s incredible how much information SPHEREx has collected in just six months — information that will be especially valuable when used alongside our other missions’ data to better understand our universe,” said Shawn Domagal-Goldman, director of the Astrophysics Division at NASA Headquarters, in a NASA statement. “We essentially have 102 new maps of the entire sky, each one in a different wavelength and containing unique information about the objects it sees.”

A Telescope That Thinks in Many Shades of Infrared

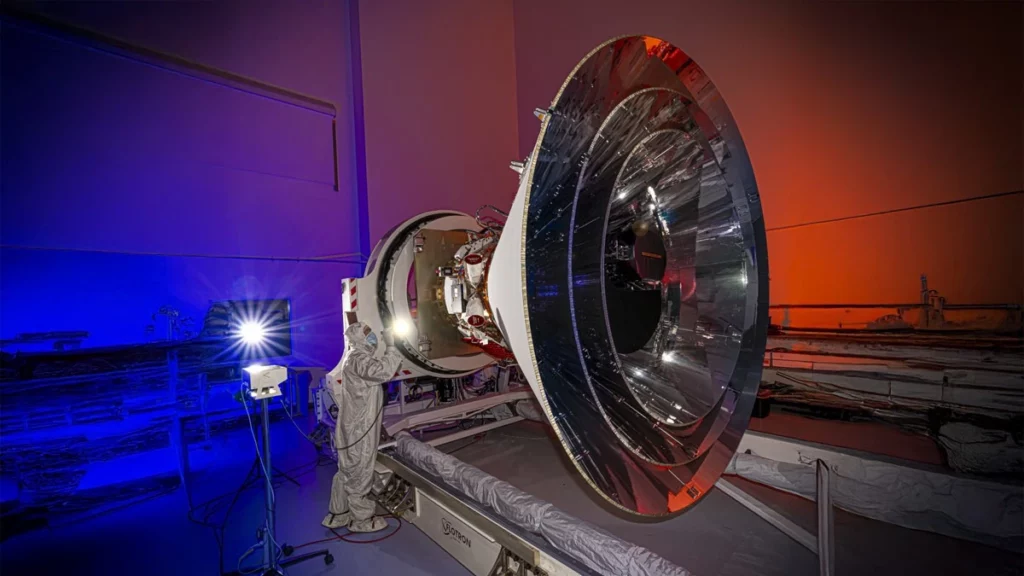

SPHEREx — short for Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization, and Ices Explorer — launched in March and began science operations in May. By December, it had finished something no previous mission has managed in quite this way: a complete all-sky survey in more than 100 colors of infrared light.

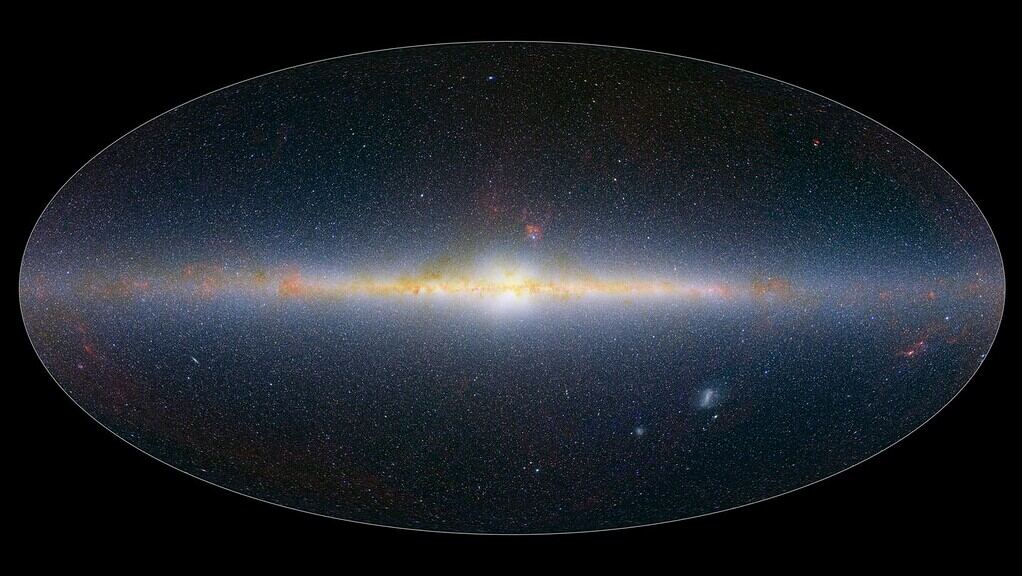

These colors are invisible to human eyes. But in space, they can reveal important developments in the history of the cosmos.

Infrared wavelengths reveal cold dust, faint galaxies, and chemical signatures that visible light misses entirely. Dense star-forming clouds that look like black voids to optical telescopes glow in infrared. Molecules like water and carbon compounds announce themselves through subtle shifts in wavelength.

Each day, SPHEREx circles Earth about 14.5 times, scanning roughly 3,600 images along a thin strip of sky. As Earth moves around the Sun, that strip shifts. After six months, the telescope has looked everywhere.

“SPHEREx is a mid-sized astrophysics mission delivering big science,” said Dave Gallagher, director of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “It’s a phenomenal example of how we turn bold ideas into reality, and in doing so, unlock enormous potential for discovery.”

Why Just 102 Colors Change Everything

Astronomers usually face a tradeoff. Some telescopes stare deeply at tiny patches of sky, collecting exquisitely detailed spectra. Others scan huge areas quickly but with limited color information.

SPHEREx wants its cake and eats it too.

With six detectors and specially designed filters that each contain 17 narrow wavelength bands, every image SPHEREx takes includes 102 distinct measurements. That makes each all-sky survey not one map, but 102 overlapping ones.

“The superpower of SPHEREx is that it captures the whole sky in 102 colors about every six months,” said Beth Fabinsky, SPHEREx project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “That’s an amazing amount of information to gather in a short amount of time.”

“I think this makes us the mantis shrimp of telescopes, because we have an amazing multicolor visual detection system and we can also see a very wide swath of our surroundings.”

From Flat Sky to 3D Universe

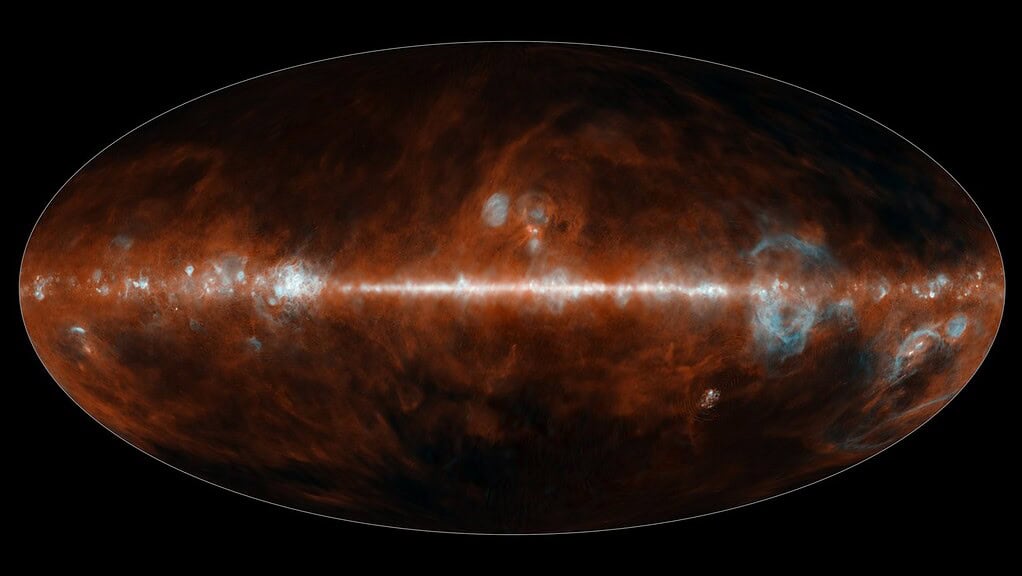

Those 102 infrared colors do more than make pretty pictures. They turn the sky into a three-dimensional map.

As the universe expands, light traveling across it stretches to longer wavelengths. Astronomers call this redshift, and it acts like a cosmic timestamp. By measuring how much a galaxy’s light has shifted across SPHEREx’s many wavelength bands, scientists can estimate its distance.

Other telescopes have already plotted the positions of millions of galaxies on the sky. Now, SPHEREx adds depth.

The mission aims to measure distances to hundreds of millions of galaxies, transforming a flat star chart into a vast 3D atlas. That structure — how galaxies cluster, spread out, and trace invisible scaffolding of dark matter — carries the imprint of inflation itself.

Scientists hope this data will reveal whether tiny quantum fluctuations in the early universe really did seed today’s galaxies, as leading theories predict.

Looking for Life’s Raw Materials

SPHEREx does not just look outward. It also looks close to home.

One of the mission’s core goals is to map key forms of ice — water, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide — within the Milky Way. These frozen molecules coat dust grains in interstellar clouds, later becoming part of planets, comets, and other heavenly bodies.

By surveying the entire galaxy, SPHEREx can show where these ingredients concentrate and how they move through cosmic ecosystems.

The telescope has already captured unusual views of objects within our solar system, including interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS. Repeated scans may also reveal supernovae, flaring stars, and other short-lived events that slip past slower surveys.

“It’s really mapping the sky in a novel way,” Olivier Doré, a cosmologist at JPL and Caltech and a SPHEREx project scientist, told Scientific American before launch. “It’s about opening up a new window on the universe.”

Standing on the Shoulders of Space Telescopes

SPHEREx arrives into a crowded but complementary fleet.

NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer previously mapped the whole sky, but in far fewer colors. The James Webb Space Telescope can perform far more detailed spectroscopy, but only across tiny fields of view.

SPHEREx sits between them, acting as a cosmic scout. It can flag intriguing regions, chemical signatures, or distant structures for follow-up by Webb and future observatories.

The mission will complete three more full-sky scans during its two-year prime operation. Combining these maps will sharpen sensitivity and reduce noise, allowing fainter and more distant objects to emerge.

Crucially, NASA has made the entire dataset publicly available.

“I think every astronomer is going to find something of value here,” Domagal-Goldman said, “as NASA’s missions enable the world to answer fundamental questions about how the universe got its start, and how it changed to eventually create a home for us in it.”

SPHEREx does not deliver a single headline-grabbing answer. Instead, it offers something subtler and more powerful: context that may trace back the origin of the cosmos itself.