This post was originally published on here

“Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links.”

Here’s what you’ll learn when you read this story:

-

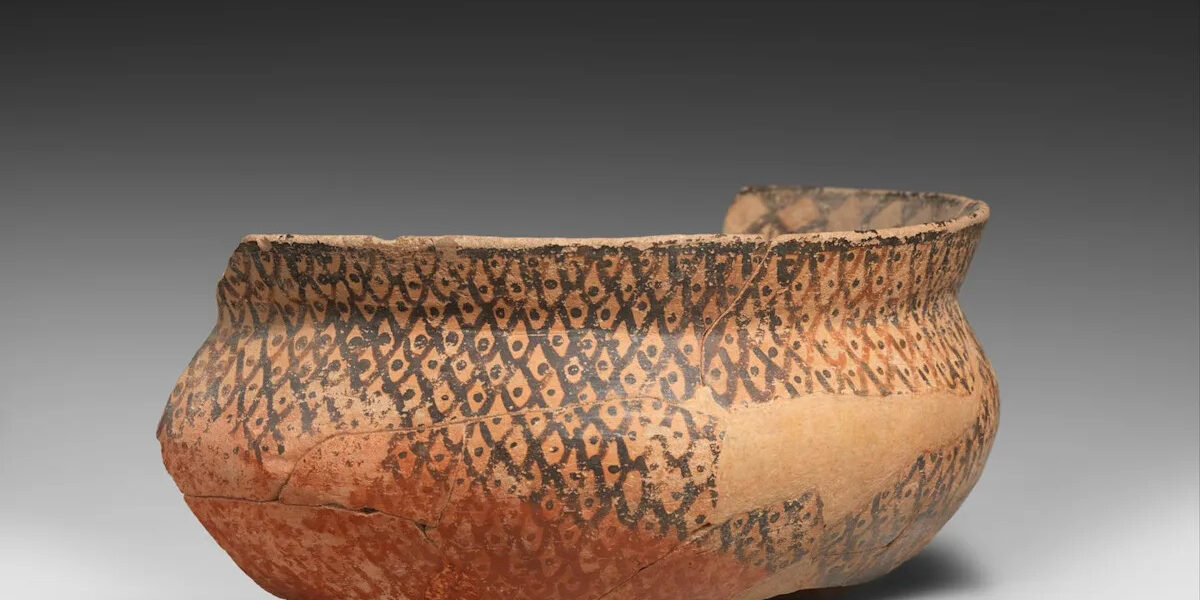

Finding evidence of ancient mathematics isn’t easy outside of written records, but a new study suggests that floral pottery from the Halafian culture of northern Mesopotamia shows evidence of geometry, symmetry, and spatial long division from before the advent of a formal number system.

-

This evidence also represents the moment when plants first became the subject of human artistic creations, as previous forms of art typically only showed animals and humans.

-

Depicted across these 700 fragments are non-edible plants like flowers, suggesting they were chose for aesthetic qualities rather than practical ones.

The world runs on a pervasive, universal language—and no, we’re not talking about Esperanto. While techniques and approaches may very, mathematical concepts across all cultures rely on the same principles. This is also why in most first contact films, scientists, governments, and/or a brawny/beautiful Hollywood performer attempts to communicate with extraterrestrials with some form of mathematics (typically something involving prime numbers).

Advertisement

Advertisement

However, this nifty universal trick also works across time. While archaeologists need reference materials—the Rosetta Stone being a famous example—to decode ancient tongues, the mathematics of ancient culture (even those from prehistory) can be easily decoded thousands of years later. In a new study published in the Journal of World Prehistory, archaeologists from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem analyzed flower motifs painted on pottery by a prehistoric culture known as the Halafian, who lived in northern Mesopotamia from 6200 to 5500 B.C.E.

Referenced as “vegetal motifs,” these depictions—spread across 700 fragments—piqued the interests of authors Yosef Garfinkel and Sarah Krulwich because they appeared to contain petals arranged in a geometric sequence: 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64. This makes these pottery fragments one of the oldest pieces of mathematical evidence from prehistory, and shows evidence of spatial long division from even before the invention of numbers, the authors argue.

“The topic of prehistoric mathematics seems at first glance to be beyond the borders of knowledgeability. Without written evidence it is difficult to assess the degree of the mathematical abilities possessed by prehistoric communities,” the authors wrote. “We argue that the vegetal decoration of Halafian pottery vessels enables some understanding of these aspects.”

As the authors note, the earliest artistic endeavors of ancient humans—at least, the ones we’ve discovered to date—contain mostly depictions of animals, including other humans. However, it’s strange that plants don’t appear in this artistic record until long after scientists know that early Homo sapiens were already using them for their various advantages. Now, the Halafian culture appears to represent the moment plant representation because a subject of human artistic curiosity.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“These patterns show that mathematical thinking began long before writing,” Krulwich said in a press statement. “People visualized divisions, sequences, and balance through their art.”

Interestingly, these motifs don’t feature edible plants, but a variety of flowers likely chosen for their inherent aesthetic rather than practical purpose. The mathematical concepts reflected across these fragments predate the first written mathematical texts from Sumer in southern Mesopotamia.

“The ability to divide space evenly, reflected in these floral motifs, likely had practical roots in daily life, such as sharing harvests or allocating communal fields,” Garfinkel said in a press statement. Once again, mathematics speaks to us across millennia.

You Might Also Like