This post was originally published on here

Far below the waves near Okinawa, a small marine worm has taken a very strange path in life. Instead of burrowing in mud like its relatives, Lanice spongicola spends its days stuck to deep-sea sponges on the seafloor.

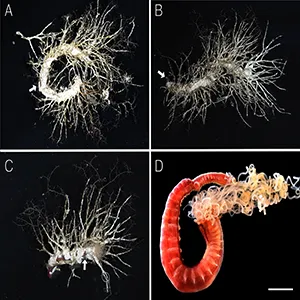

This newly-discovered worm grips its sponge host with a row of suction pads along its underside. Those pads let it live in a part of the ocean floor where loose sediment is almost completely missing.

Lanice spongicola breaks rules

The newly-described animal is a polychaete, a segmented marine worm with many bristles, in the terebellid family.

Most terebellids build tubes in soft seafloor sediment and feed by stretching out long, thin tentacles to catch drifting particles.

The work was led by Naoto Jimi, a lecturer at Nagoya University in Japan. His research centers on the diversity of marine worms and how they adapt to unusual habitats.

Lanice spongicola was found on a tall glass sponge off Minamidaito Island in the northwestern Pacific Ocean at a depth of about 2,800 feet.

One study reports that its body carries a series of suction pads on the belly side that help it stay attached. In the terebellid family, that kind of life on bare rock without surrounding sediment is extremely rare.

Most known species depend on mud or sand, so this worm shows that even a “sediment loving” group can sometimes escape that rule.

Life on a glass sponge tower

Lanice spongicola lives on a glass sponge, a deep-sea sponge with a skeleton made of silica, that rises from hard rock.

The worm builds a thin mucus tube on the lower part of the sponge and presses its underside firmly against the tube wall.

The underside pads are deeply grooved and dark, forming a mid-line structure that acts like an adhesion organ.

They let the worm resist strong currents that would normally sweep a soft bodied animal away from such a steep, clean surface.

Deep sea slopes like this are part of huge underwater landscapes shaped by old reefs and dissolved rock, known as karst, a landscape formed as rock dissolves creating steep features.

These steep areas rarely collect loose sediment, so animals that depend on mud must either adapt or stay away.

Based on satellite gravity data, researchers estimate that the world’s oceans may hide around 25 million underwater mountains more than 330-feet tall.

Many of these slopes and peaks likely host similar sediment poor habitats that are still almost unknown.

Suction-pads made for a sponge

The suction system used by Lanice spongicola sits on segments near the head and forms a continuous pad running along the midline.

Further back on the body, the pads become shallow and lose the thick raised edges, which hints that the front region does most of the gripping.

Suction structures have evolved many times in animals, from fish to leeches, and they usually serve for clinging or feeding.

In this case the pads seem tuned for life in symbiosis, two species living closely with direct interaction, with a particular sponge rather than for roaming around.

The team’s genetic tests showed that Lanice spongicola falls inside the terebellid family, but its exact position is still unclear because different genes gave conflicting results.

That uncertainty leaves open the question of whether similar suction-pads might exist in other, still unknown relatives.

Deep sea sponges as habitats

Glass sponges and other large sponges act as habitat builders on the seafloor. In the Northwest Atlantic, areas with dense sponge “grounds” hold more species and higher numbers of animals than nearby bare bottom.

Glass sponge reefs off western Canada filter seawater so quickly that they remove large amounts of bacteria and carbon from the water column.

Those reefs process such high volumes of water that they rank among the most intense seafloor filter feeding communities known.

Sponges can even serve as natural biological samplers. In a North Atlantic project, DNA trapped inside sponge tissues revealed more than 400 animal species in a single deep sea survey.

Why this odd worm matters

Lanice spongicola shows how a small change in body design can open access to a new kind of habitat.

By turning a simple belly pad into a strong suction-strip, a typical sediment-dwelling worm has become a sponge specialist.

The discovery also hints that deep sea biodiversity is still seriously under-counted. Even in well studied regions, new worms, snails, and crustaceans keep appearing whenever researchers sample hard to reach habitats in detail.

Modern deep-sea work depends heavily on the remotely operated vehicle, tethered robot submarine guided from a ship, which can hover close to sponge branches without damaging them.

Without these robots, a small worm glued to a single glass sponge in a rocky canyon might easily have been missed forever.

Lessons from Lanice spongicola

Finding a terebellid that has abandoned sediment-living supports the idea that evolution often explores every possible niche.

Organisms that once seemed restricted to one lifestyle may in fact have offbeat relatives adapted to very different places.

For conservation, this matters because activities like mining, trawling, and cable laying increasingly reach deep slopes and sponge grounds.

Damaging a single rocky outcrop or sponge stand could wipe out entire lineages that science has only just started to notice.

The discovery of Lanice spongicola adds one more strand to the story of how life copes with cold, dark, and sediment-free conditions on the deep seafloor.

Every such find gives researchers a better sense of how body form, behavior, and habitat link together over evolution.

The study is published in Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–