This post was originally published on here

A newly identified virus–cell hybrid structure allows viruses to spread faster and more aggressively by hitching a ride on migrating cells.

Viruses rely on efficient movement between cells to establish infection and cause disease. Unlike bacteria, viruses cannot reproduce on their own and must enter host cells to multiply, making the way they spread a key factor in how severe an infection becomes.

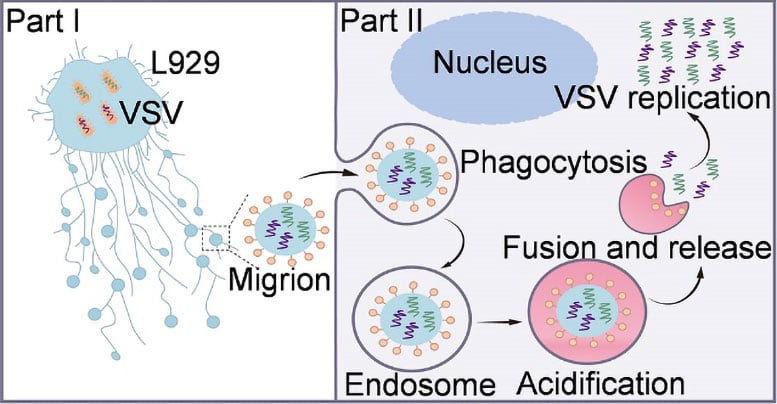

In a study published in Science Bulletin, scientists from Peking University Health Science Center and the Harbin Veterinary Research Institute uncovered an unexpected route that vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) uses to move from one cell to another. They found that infected cells actively shuttle viral genetic material and proteins into migrasomes, recently identified cellular structures that form when cells migrate.

Migrasomes normally help cells communicate by releasing packages of biological material as they move. In this case, some migrasomes were loaded with viral nucleic acids and displayed the viral surface protein VSV-G. The researchers named these virus carrying structures “Migrions.”

Unlike individual VSV particles, Migrions are much larger and function as virus-like assemblies rather than conventional free virions. When VSV spreads through Migrions, viral replication begins more quickly than when cells are infected by free virus particles. This appears to happen because multiple copies of the viral genome are delivered together, allowing replication to start simultaneously within a single host cell.

A Distinct Transmission Pathway

The study also showed that Migrions can carry more than one type of virus at the same time, enabling the co-transmission of heterologous viruses.

This behavior sets Migrions apart from known extracellular vesicle (EV)-mediated routes of viral spread, which typically transport limited viral cargo. Further experiments revealed that Migrions enter recipient cells through endocytosis without relying on specific viral receptors on the cell surface, highlighting a fundamentally different and more flexible pathway for viral entry.

Under acidic conditions, VSV-G on Migrions triggers membrane fusion with endosomes, releasing viral cargo, which is essential to initiate replication. In murine infection models, Migrions demonstrated significantly enhanced infectivity and pathogenicity relative to free virions, causing severe pulmonary and cerebral infections characterized by encephalitis and lethal outcomes.

Implications for Viral Transmission Models

The researcher proposed that “Migrion”—a chimeric structure formed between virus and migrasome—represents a novel paradigm of intercellular viral transmission, one that directly couples viral dissemination with cell migration.

This discovery challenges conventional models of viral spread by introducing a migration-dependent mechanism that exploits the host’s migratory machinery for systemic infection.

Reference: “Migrion, a Migrasome-mediated unit for intercellular viral transmission” by Yuxing Huang, Xiaojie Yan, Xing Liu, Congcong Ji, Wenmin Tian, Haohao Tang, Yong Li, Yiling Wen, Peiyao Fan, Hongli Wang, Cankun Xi, Zhongtian Li, Tian Lu, Fuping You, Xin Yin and Yang Chen, 23 August 2025, Science Bulletin.

DOI: 10.1016/j.scib.2025.08.039

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.