This post was originally published on here

Imagine diving beneath the surface and finding a forest of sculptures, living corals, and thriving fish communities where barren sand once lay. That’s the revolution unfolding across our oceans. Artificial reefs, powered by bold science and visionary conservation groups, are transforming damaged coastlines into vibrant marine sanctuaries, one structure at a time.

—

Artificial reefs have become an important intervention in marine ecosystem conservation. These artificial structures aim to mimic natural coral formations, providing habitat for marine life and contributing to the restoration of degraded underwater environments.

The urgency of such interventions becomes evident when examining current reef loss. Coral reefs occupy merely 1% of the ocean floor, yet they support at least 25% of all marine species. They function as nurseries where fish and invertebrates spawn, shelter, and mature before migrating to open waters, serving as essential breeding grounds that replenish fish populations and sustain fisheries globally. Reefs provide an estimated $36 billion to the global economy every year. They act as natural breakwaters, absorbing wave energy and helping protect coastlines against erosion, storm surge and flooding.

In the United States, about half of all federally managed fisheries depend on coral reefs and related habitats during their life cycles, and coral reef fisheries contribute over $100 million annually to the nation’s economy.

But threats including global warming and ocean acidification, overfishing, pollution and coastal development are rapidly degrading coral reef ecosystems. Record high ocean temperatures in the past two years have led to the largest coral bleaching ever recorded, affecting 84% of the world’s reefs.

Given their countless benefits, reef ecosystem collapse poses real threats to food security, coastal protection, and any billions-worth of economic and cultural services they provide. Restoration initiatives like artificial reefs are thus a high priority for scientists, communities, and conservation organizations.

What Are Artificial Reefs?

Artificial reefs are man-made underwater structures designed to simulate some of the features of a real reef. They are typically deployed on flat or eroding ocean bottoms in order to provide habitat for marine life. They come in many forms: submerged shipwrecks, decommissioned oil platforms, concrete modules or “reef balls”, and piles of rock or repurposed materials such as tires and pipes. The objective is to have a hard, three-dimensional substrate to which corals, algae and marine invertebrates can attach and grow, as well as a substrate where fish can seek shelter.

Infrastructure not originally intended for marine habitat enhancement often functions as accidental artificial reefs. Bridge pilings, lighthouse foundations, and other coastal structures attract marine life through their provision of hard substrate in otherwise featureless environments.

Contemporary artificial reef projects predominantly utilize materials selected for their durability, non-toxicity, and longevity, including natural rock, marine-grade concrete, and corrosion-resistant steel. These non-porous materials resist degradation in the marine environment and provide stable attachment surfaces for decades, ensuring long-term ecological benefits.

Benefits of Artificial Reefs

Enhance habitat complexity

Well-designed artificial reefs come with other ecological and economic benefits, such as enhancing habitat complexity. Additional structures with a lot of nooks and ledges provide shelter and breeding sites for fish, crustaceans, mollusks and other reef life. Studies show fish diversity and abundance often increase around new reefs as species colonize the added habitat in the form of coral in the ocean. This, in turn, can help boost local fisheries, as they can help provide safe nursery areas for commercially important species.

Support restoration of coral and habitat

Artificial reefs provide marine resource managers with a substrate for transplanting corals, oysters, mangroves, and seagrasses.

For instance, the Ocean Rescue Alliance International (ORAI) – a marine conservation non-profit focused on restoring marine ecosystems through reef restoration projects – integrates gray infrastructure concrete reef structures with active coral propagation through ocean-based nurseries. Their modules incorporate attachment points – threaded receptacles – that allow researchers to mechanically secure lab-cultivated coral fragments to the reef structure. This method significantly accelerates the transplantation process.

This hybrid “green and gray” approach facilitates the expedited re-establishment of reef ecosystems in areas where natural reefs have experienced degradation.

Provide coastal protection

Artificial reefs have the ability to serve as submerged breakwaters. By slowing down and breaking waves, they help maintain beach sand and reduce erosion. ORAI’s reef modules can reduce about 75% of incoming wave energy, on average, similar to the way offshore breakwaters buffer shorelines. This reduces the need to dredge the beaches or use seawalls protecting coastal communities.

Increase ecotourism and education

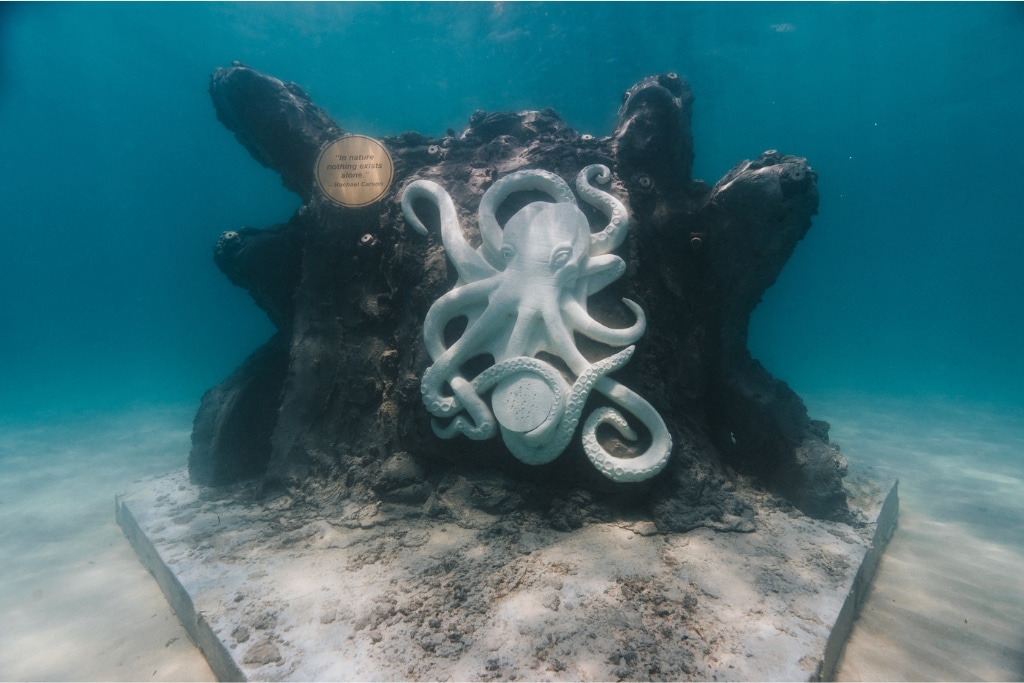

Creative installations such as sunken sculptures or shipwrecks attract people and bring awareness. For example, Global Coralition’s goddess Mazu sculpture in Thailand and Counting Coral’s Sculptural Coral Gene Banks use artistic statues as reef modules to create underwater parks that are of interest to tourists and students. This also helps boost conservation awareness.

Challenges and Limitations

Artificial reefs are not the ideal replacement for real reefs, and ill-planned projects can fail or lead to pollution of the marine ecosystem

Lack of natural complexity

Artificial reefs made, for example, from piles of tires, concrete blocks, or ships are fairly simple structures. Without complexity, artificial reefs can be used by only a few hardy species and have no real chance of becoming rich ecosystems.

Concerns of material and pollution

Using inappropriate materials risks polluting waterways or creating marine debris. Old tire reefs are a notorious case: millions of tires were sunk off the coast of Florida in the 1970s, and they eventually broke loose, posing a threat to the area’s corals. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration invested about $2.5 millions in removing debris.

Even concrete has to be carefully formulated in order to avoid harmful runoffs. Material choice and testing is therefore critical for safety.

Biological and ecological hazard

Artificial reefs can displace natural habitats if they are put in a sensitive location. They can also alter the current and sediment flow, and inadvertently promote invasive species. Another particularly significant concern is their influence on fishing activity. Because artificial reefs tend to attract and concentrate fish populations, they frequently become focal points for fishermen. This concentration of effort is referred to as fishing pressure, meaning that a disproportionate amount of harvesting occurs in a limited area. If the rate of removal exceeds the natural reproductive capacity of the species, the result is overfishing, which leads to population decline and long‑term ecological imbalance.

Poor placement of reef modules can harm nearby natural coral reefs by disrupting the natural flow of water, altering sediment movement, or blocking essential sunlight, all of which are critical for coral growth and survival.

Innovative Reef Restoration Organizations and Projects

Artistic Reefs

ORAI develops sculptural reef modules that use ecological function and cultural appeal. ORAI’s Founder Shelby Thomas explains that art is “the perfect medium” to engage people with conservation. The team casts lifelike figures (mermaids, marine animals, mythological figures) into structures in the reef.

These artistic reefs use patented marine-grade concrete and feature dozens of screw-in connectors for coral fragments. Each module provides immediate fish shelter, while the artificial base becomes “the skeleton for the coral,” dramatically accelerating restoration.

Similar initiatives exist globally. Australia’s Museum of Underwater Art (MOUA) features Jason deCaires Taylor’s 16-meter long Coral Greenhouse made from pH-neutral concrete, its porous structure providing an ideal substrate for coral recruits and attracts other marine life. The EU-funded ART4SEA project placed eco-themed sculptures off Italy, Greece, and Malta, while Grenada’s Molinere Underwater Sculpture Park supports diverse aquatic life on formerly barren seabed.

Engineering-Driven Reef Structures

Outside of art, there are also many organizations that use novel engineering to construct reefs. The Reef Ball Foundation (US) has produced about half a million concrete “reef balls” – hollow dome modules – and “conducted over 6,000 projects in over 62 countries” to restore coral habitats. These prefabricated balls imitate the complexity of the reef and even help to break the wave energy.

In Australia, the Reef Design Lab created a 3D printed modular system to rebuild the reefs by hand, the ceramic lattice blocks can be dropped from small boats and filled with concrete – all without heavy equipment.

Community-Led Restoration Initiatives

Many NGOs also use a combination of these techniques in conjunction with local coral gardening. In Southeast Asia, Bali’s Ocean Gardener and Indonesia’s Coral Guardian have active nursery and transplant programs. Reefscapers, a marine consultancy based in the Maldives, pioneered coral frame technology since 2005; their founders have stated that their shallow water coral nurseries and frames “rank among the most successful marine conservation programmes in the world.”

The Caribbeans are home to an abundance of high-tech farming and community reef projects. For example, Coral Vita in the Bahamas is an accelerated land-based coral farm where scientists can grow corals up to 50 times faster and select for thermal tolerance before outplanting them. Volunteer-driven organizations in the region are using simpler techniques: Bonaire’s Reef Renewal Foundation mobilizes dive volunteers to plant corals and have “developed new and innovative ways to restore reefs,” emphasizing that “through community efforts there is still hope for coral reefs.” Their projects are serving as a model for the effectiveness of hands-on planting as a way to measurably increase local reef health.

Even Europe’s Mediterranean sees such work now: Spanish NGOs such as Coral Soul and Coral Guardian have partnered to set up “the first coral nursery of the Mediterranean Sea” off Granada to restore endangered cold water coral.

By blending creative bits of design, engineering know-how and the communal profession of science, organizations are all over the world building reef structure and resilience again. As one of the Reef Ecologic/MOUAs reports states, these underwater sculptures and structures “offer a fresh and immersive perspective on the reef’s ecology” while also serving as active renewable reef habitat.

When carefully designed, artificial reefs have the potential to be amazing instruments in marine conservation. They use the power of engineering and ecology to restore lost habitats, fisheries and shorelines. But they do need to mimic the complexity in nature and be combined with active biology (such as coral farming) in order to work.

The examples illustrated in this piece show that it is possible to combine art and science and produce a reef that is practical and highly aesthetic and still ensures these “cities of the ocean” can flourish for generations to come.

Featured image: National Parks Gallery.

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us