This post was originally published on here

‘Peptide detective’ Weizmann immunologist Prof. Yifat Merbl was recognized for a new hidden immune mechanism.

The brilliant mind and determination of Prof. Yifat Merbl – a senior systems biologist/immunologist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot – have overcome the hostility faced by Israel in much of the world’s scientific communities and crowned Merbl her as one of the 10 people who shaped science in 2025, according to the list published in the prestigious journal Nature.

The selection recognizes important scientific trends and discoveries over the course of the year and tells the stories of the people involved. It is compiled by Nature’s editors – without recommendations from colleagues or personal campaigns – to highlight some of the most influential research and important developments shaping our world.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Just last year, Merbl received the Rappaport Prize for Biomedical Research in the Promising Researcher category – one of Israel’s most prestigious scientific awards – which is given annually to scientists for groundbreaking or innovative research that has the potential to advance the health of mankind.

Her research involves the proteasome, the cellular “garbage can” that specializes in eliminating proteins that have completed their functions or have been damaged and need to be sent for degradation. Looking at the contents of the cellular trash cans can reveal details about the cell’s lifestyle and what goes on inside, which are difficult to discover through other means, the researcher explained.

Using this technology, the team has previously discovered a pathological mechanism that enables cancer cells to escape detection by the immune system, by changing the cellular trash cans and the way the proteins inside them are degraded. It could also lead to improved cancer immunotherapy by identifying which patients would respond to treatments that make cancer cells “visible” again or prevent immune evasion. It may advance personalized medicine because the new tools can measure protein breakdown in individual cells and create tailored immune treatments and personalized cancer therapy.

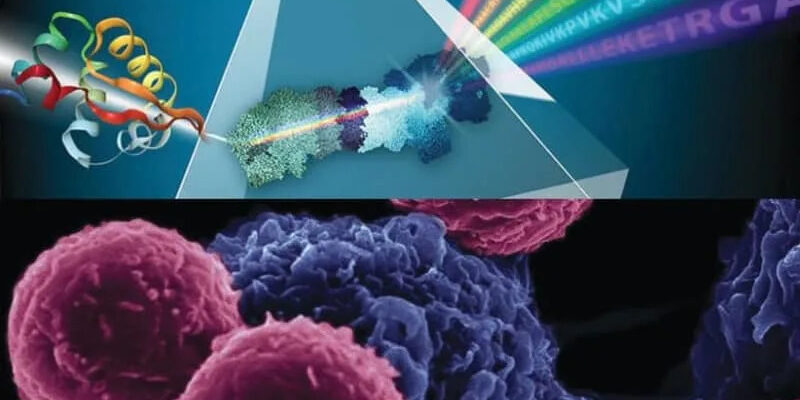

AN ILLUSTRATION of Merbl’s recent discovery (credit: WEIZMANN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE)

Israeli scientists won award for discovery on new immune mechanism

THE LATEST Nature recognition is for a new immune mechanism that was hidden inside the little pieces that proteins are broken down into.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Merbl and her lab of 20 researchers and students – including 11 women, Israelis, and foreigners from India, China, Italy, Russia, and Austria – discovered a new immune function of cellular “trash-processed” pieces bearing antimicrobial functions, which may lead to the development of new antimicrobial drugs. Her lab showed that such pieces, called peptides, may target bacteria directly by rupturing their membranes.

They found that most of the proteins in our body are predicted to have at least one such peptide, which may be able to kill bacteria when the protein is broken down. It is interesting to note that these peptides are found within proteins that are not necessarily related to immune functions and are spread across the proteome. As such, the lab has identified an untapped resource of potential “natural antimicrobial agents.” This is valuable because antibiotic resistance is one of the biggest threats to global health.

Beyond novel therapies, the lab’s findings could move towards detecting disease-triggered changes in protein fragments, early warning systems for autoimmune disorders, and more-sensitive cancer diagnostics.

Others on Nature’s list included the Chinese finance wizard who developed the DeepSeek AI model and stunned the world; an agricultural engineer and entomologist who bred insects to combat disease; a pioneer of deep-sea exploration who discovered animal ecosystems; a physicist whose work led to the first images from the revolutionary astronomical Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile taken with the world’s largest digital camera; and a neurologist offering hope for Huntington’s disease using gene therapies.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“I had no idea I was going to be included until I was interviewed by a journalist from Nature who informed me that I had been nominated,” Merbl – who has been dubbed a “peptide detective” – told The Jerusalem Post in an interview.

Prof. Yifat Merbl: From Givat Shmuel to Nature’s top science shapers

GROWING UP in the Ramat Ilan neighborhood of Givat Shmuel in the center of the country, Merbl served as an officer in the Israel Air Force, but decided that she was “not suited to a military career.” She completed a bachelor’s of science degree at Bar-Ilan University in computational biology and a master’s degree in immunology at the Weizmann Institute, under the supervision of esteemed immunologist Prof. Irun Cohen (now 89), who made key discoveries relating to autoimmunity and diabetes. Though her research went in a different direction, she values the time in his lab as an entry point into immunology.

In 2010, she earned her doctorate in systems biology with Prof. Marc Kirschner at Harvard Medical School, where she also continued for post-doctoral training before returning to Weizmann as a principal investigator to open her own lab.

Merbl said she did not have a lab scientist as a role model in her family. Her parents retired, one as an energy engineer and the other a lawyer, and she has a twin sister who is a veterinarian and an older brother who is a sports therapist and osteopath.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2004 was awarded jointly to Aaron Ciechanover, Avram Hershko, and Irwin Rose for the discovery of “ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation” and thereby contributed groundbreaking knowledge of how the cell can dispose of certain proteins, in a highly controlled manner, by marking unwanted proteins with a label consisting of the polypeptide ubiquitin. Proteins so labeled are then rapidly broken down – degraded – in the cellular “waste disposers” called proteasomes. Merbl’s discovery sheds new light on yet another role that has not been previously known: how the broken pieces may serve as a cell-autonomous source of immunity.

THE FOCUS on proteasomal degradation and the “waste disposers” is only one technology of the Merbl lab. On other fronts, they study the “epiProteome,” which is the dynamic regulation of proteins after they have been made, including chemical changes, called post-translational modifications. Together with the lookout into degradation, their unique technologies uncover “hidden layers” of biology, beyond the genome, which determine the fate of proteins and impact the functions of cells.

Merbl often integrates diverse expertise, including biochemistry, immunology, cell and computational biology, and animal in vivo models in her studies. This interdisciplinary perspective allows her lab to contribute across different human pathologies such as cancer, infectious disease, and neurodegeneration.

But the researcher and her team had setbacks. During the war with Iran last June, ballistic missiles destroyed numerous labs at Weizmann, including theirs in the Wolfson Building – causing millions of dollars of damage to equipment and the loss of samples that will not be easily replaced. The Rehovot institute moved them to another building that had survived and purchased equipment they needed.

“I was at home when the missile landed. I operated on “automate mode” and reminded myself that it could have been much worse. The Weizmann management was amazing in its response, finding new locations for about 50 labs that were demolished, so that science can continue, even at times of such great challenges.”