This post was originally published on here

Using lab-grown brain tissue, researchers uncovered complex patterns of neural signaling that differ subtly between healthy brains and those linked to severe psychiatric disorders.

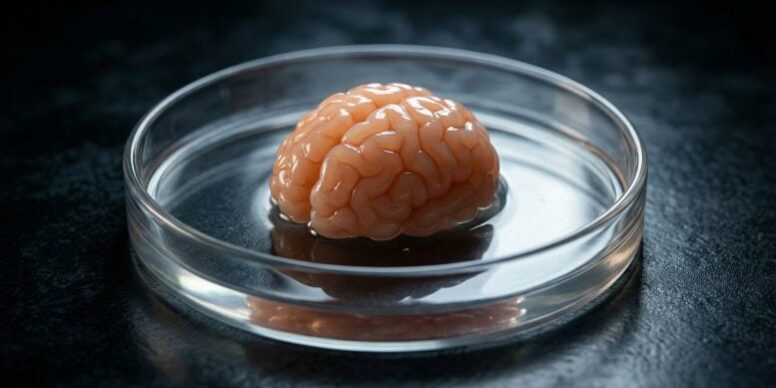

For the first time, scientists have used pea-sized brain organoids grown in the laboratory to uncover how neurons may malfunction in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. These psychiatric conditions affect millions of people around the world, yet they remain difficult to diagnose because researchers still lack a clear understanding of their underlying molecular mechanisms.

The results could eventually help clinicians reduce diagnostic uncertainty when treating these and other mental health conditions. At present, such disorders are typically identified through clinical judgment alone, and treatment often relies on lengthy trial-and-error approaches to medication.

A detailed account of the findings was published in the journal APL Bioengineering.

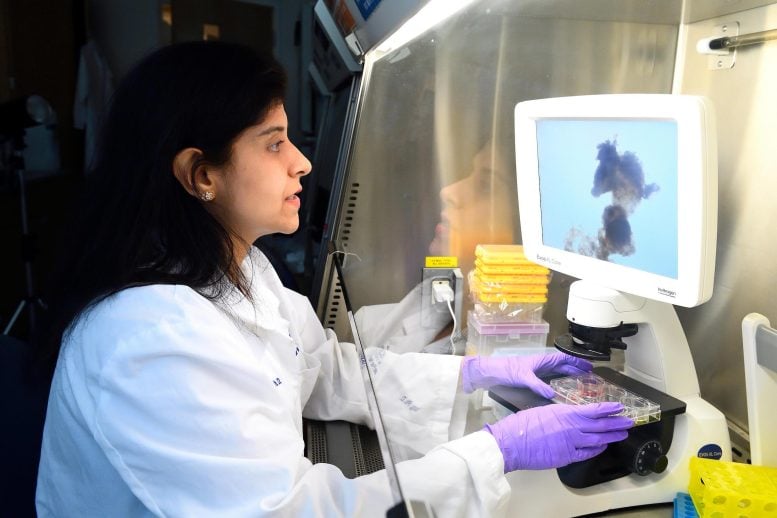

“Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are very hard to diagnose because no particular part of the brain goes off. No specific enzymes are going off like in Parkinson’s, another neurological disease where doctors can diagnose and treat based on dopamine levels even though it still doesn’t have a proper cure,” said Annie Kathuria, a Johns Hopkins University biomedical engineer who led the research. “Our hope is that in the future we can not only confirm a patient is schizophrenic or bipolar from brain organoids, but that we can also start testing drugs on the organoids to find out what drug concentrations might help them get to a healthy state.”

Machine learning decodes disease specific signals

Kathuria’s team created the organoids, simplified versions of brain tissue, by reprogramming blood and skin cells from people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and from healthy volunteers into stem cells capable of forming brain-like structures. They then applied machine learning tools to analyze the electrical activity of the organoids’ cells, allowing them to identify neural firing patterns associated with healthy and diseased states. In the human brain, neurons communicate through small electrical signals.

Specific features of this brain-like activity acted as biomarkers for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, enabling the researchers to correctly identify the origin of the organoids with an accuracy of 83 percent. After applying gentle electrical stimulation to uncover additional neural activity, that accuracy increased to 92 percent.

Disorder-specific electrical signatures

The newly identified patterns reflected complex electrophysiological behavior unique to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Neural firing spikes and timing changes occurred simultaneously across multiple parameters, producing distinct electrical signatures for each condition.

“At least molecularly, we can check what goes wrong when we are making these brains in a dish and distinguish between organoids from a healthy person, a schizophrenia patient, or a bipolar patient based on these electrophysiology signatures,” Kathuria said. “We track the electrical signals produced by neurons during development, comparing them to organoids from patients without these mental health disorders.”

To study how the organoids’ cells formed neural networks with one another, they placed them on a microchip fitted with multi-electrode arrays resembling an electrical grid. The setup helped them streamline data as if it came from a tiny electroencephalogram, or EEG, which doctors use to measure patients’ brain activity.

Fully grown with about three-millimeter diameters, the organoids pack various kinds of neural cell types found in the brain’s prefrontal cortex, which is known for its higher cognitive functions. They also contain myelin, cellular material that wraps around nerves like insulation around electrical wires to improve networking of the signals needed by the brain to communicate with the rest of the body.

Toward personalized psychiatric treatment

The research only involved 12 patients, but the findings will likely have real-world, clinical application, Kathuria said, as they could be the beginning of an important testbed for psychiatric drug therapies.

The team is currently working with neurosurgeons, psychiatrists, and other neuroscientists at the John Hopkins School of Medicine to recruit blood samples from psychiatric patients and test how various drug concentrations might influence their findings. Even with a small sample, the team could start suggesting drug concentrations that might work on a patient if they can normalize the organoid’s conditions, Kathuria said.

“That’s how most doctors give patients these drugs, with a trial-and-error method that may take six or seven months to finds the right drug,” Kathuria said. “Clozapine is the most common drug prescribed for schizophrenia, but about 40% of patients are resistant to it. With our organoids, maybe we won’t have to do that trial-and-error period. Maybe we can give them the right drug sooner than that.”

Reference: “Machine learning-enabled detection of electrophysiological signatures in iPSC-derived models of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder” by Kai Cheng, Autumn Williams, Anannya Kshirsagar, Sai Kulkarni, Rakesh Karmacharya, Deok-Ho Kim, Sridevi V. Sarma and Annie Kathuria, 22 September 2025, APL Bioengineering.

DOI: 10.1063/5.0250559

This work was supported by NIH grants R01MH113858 and K08MH086846 (to R.K.), and R01NS133965 (to D.-H.K.).

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.